Moss thrives in our wet, rainy region. Given enough time and clear space, such as a roof, a green carpet will slowly form. So prolific is moss that entire companies exist to control it and in the drizzly Pacific Northwest, those companies tend to do well.

Moss thrives in our wet, rainy region. Given enough time and clear space, such as a roof, a green carpet will slowly form. So prolific is moss that entire companies exist to control it and in the drizzly Pacific Northwest, those companies tend to do well.

But moss can also be a welcome interloper or an intentional landscape component. Gardens devoted specifically to moss are uncommon, but West Sound is fortunate to have a green gem: the Moss Garden at the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island. While many public gardens make extensive use of moss, the Bloedel Reserve moss garden stands out because moss is the primary focus, not just a major part of the garden.

History

History

Timber magnate Prentice Bloedel and his wife, Virginia, originally purchased some of the land in 1951 that would eventually become the Bloedel Reserve. Over the following decades, they added more land, eventually bringing their property to its current 150-acre size. Part of the land was allowed to remain forest. Other parts purchased from previous land owners were left to return to a more natural state.

Still other areas were developed into specific gardens over the years: the Reflection Pond, the Glen, the Japanese Garden and several others. In the early ’80s, Prentice Bloedel engaged accomplished landscape architect Richard Haag to create four garden “rooms.” These were Birdmarsh, the Reflection Pond, the Moss Garden and the Garden of Planes that was later converted into what is now the Stone Garden, located in front of the guest house within the Japanese Garden.

The decision to install a moss garden was borne from a couple different experiences. First, Richard Haag and the Bloedel Reserve’s first executive director, Richard Brown, attended an annual meeting of the American Public Garden Association at the University of British Columbia.

While there, Haag and Brown observed the liberal use of moss within the Nitobe Japanese Garden. The combination of dark stems of red huckleberry against the green, velvet moss carpet was particularly striking. Upon returning to Washington, they related their impressions to Prentice Bloedel.

While there, Haag and Brown observed the liberal use of moss within the Nitobe Japanese Garden. The combination of dark stems of red huckleberry against the green, velvet moss carpet was particularly striking. Upon returning to Washington, they related their impressions to Prentice Bloedel.

Around the same time, the Bloedels’ daughter, Virginia Wright, and her husband returned from travelling in Japan. The shared many photos taken of Japanese gardens with their parents. Prentice Bloedel was impressed by the extensive use of moss within authentic Japanese gardens. He was sold on the idea and decided to create a moss garden on his own property.

Together with Haag and Brown, they chose an approximately one-acre plot with a high water table bordering the northwest corner of the reflection pond as the future location of the moss garden. In late 1982, work began on the site.

What was largely a salmonberry bog with lots of red alder was cleared of most underbrush. Many alders were removed but not all; Prentice Bloedel was quite fond of the species and directed workers to preserve many specimens on the western edge of the garden.

With the land cleared of most undergrowth, the garden crew set about establishing moss. Rather than plant moss directly, they planted 275,000 starts of Irish moss — a flowering plant that only resembles moss. It was hoped that the native mosses would take over within five years or so.

With the land cleared of most undergrowth, the garden crew set about establishing moss. Rather than plant moss directly, they planted 275,000 starts of Irish moss — a flowering plant that only resembles moss. It was hoped that the native mosses would take over within five years or so.

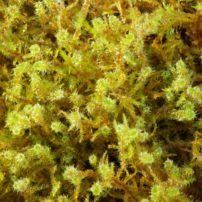

Native mosses indeed came in and filled in as hoped. Thirty-six years later, there are at least 45 species of native mosses and liverworts identified within the moss garden. The ground is a soft, green carpet and moss coats logs, rocks, tree bases and branches. It is now much different than its original brambly, boggy state.

Mosses

Among the more common mosses are bent-leaf moss (Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus) and pointed-spear moss (Calliergonella cuspidata). Both commonly found in lawns, they also thrive in the sunnier portions of the moss garden. Rather than the usual green, these two species tend toward golden green. The amount of gold coloration increases with higher sunlight levels.

At the opposite end of the “moss color spectrum” is broom forkmoss (Dicranum scoparium). Its shade of green can be described as “happy.” It is an unusually bright-green, tuft-forming moss and within the Bloedel Reserve moss garden, it is readily identified by color alone. Compared to bent-leaf moss and pointed-spear moss, it prefers a little more shade and grows on the ground, rotted logs and occasionally tree bases.

At the opposite end of the “moss color spectrum” is broom forkmoss (Dicranum scoparium). Its shade of green can be described as “happy.” It is an unusually bright-green, tuft-forming moss and within the Bloedel Reserve moss garden, it is readily identified by color alone. Compared to bent-leaf moss and pointed-spear moss, it prefers a little more shade and grows on the ground, rotted logs and occasionally tree bases.

Other frequent ground-dwellers are juniper haircap (Polytrichum juniperinum) and bank haircap (Polytrichastrum formosum). Bank haircap is a relatively large moss, growing up to several inches tall in patches that resemble forests of green bottlebrushes. Juniper haircap is a bit smaller and has leaves tipped in reddish brown though magnification may be needed to see this feature easily.

Other frequent ground-dwellers are juniper haircap (Polytrichum juniperinum) and bank haircap (Polytrichastrum formosum). Bank haircap is a relatively large moss, growing up to several inches tall in patches that resemble forests of green bottlebrushes. Juniper haircap is a bit smaller and has leaves tipped in reddish brown though magnification may be needed to see this feature easily.

Perhaps the most common moss within the garden is Selwyn’s smoothcap (Atrichum selwynii). A dark-green, upright moss, it carpets shady ground like a miniature woodland. Like all mosses, this species annually grows spore-producing structures called “sporophytes.” Selwyn’s smoothcap produces these so prolifically beginning in late summer that they give the garden floor a nice reddish “frosting” over its green carpet that lasts into the winter.

Moss Maintenance

Maintaining a moss garden is not difficult but it involves a lot of labor. The key to a successful moss garden is frequent weeding to suppress competition between moss and weeds. Leaf cleanup in autumn is also crucial.

Anything that covers the moss should be removed. Lack of adequate sunlight and competition from other plants will thin out a moss carpet.

Summer irrigation of the moss garden helps keep up appearances but, perhaps counterintuitively, it is not absolutely necessary for moss survival. Mosses gain and lose water in rhythm with their environment.

As their surroundings dry out, so do mosses. When the rains come, mosses soak up the first drops readily.

To cope with drought periods, mosses have evolved an amazing drought tolerance. Most species are able to dry out completely for months at a time.

To cope with drought periods, mosses have evolved an amazing drought tolerance. Most species are able to dry out completely for months at a time.

But as soon as they are wetted, they will begin growth within minutes as if they’d had adequate moisture all along. This ability makes them even more drought tolerant than cacti.

Irrigating an established moss garden is therefore low stress for gardeners. Water is only necessary for making the moss appear lush and vibrant. It is also useful for maintenance: Hydrated moss is more wear resistant than dry moss. Watering before weeding reduces wear and tear from gardeners performing their duty.

When starting a new moss garden, however, water is more important. For new moss to fill in, it needs to grow. To be able to grow, it needs water. An occasional dry period is fine but keep up on light summer watering of new moss patches until they fill in.

Historically, the moss garden at the Bloedel Reserve has been assigned a single gardener who is rarely wanting for moss-related tasks. To assist, the reserve’s strong volunteer program allows volunteers to sign up to work in the moss garden. It is a most welcome endeavor.

What Makes a Moss Garden

In other gardens, moss is used to complement other plants. The reverse is true in a moss garden. While there does not seem to be an official definition of a moss garden, at the Bloedel Reserve, a few simple rules are followed to ensure that the moss garden is indeed a “moss garden.”

First, open space is encouraged to allow for large swaths of moss. Visual interest is derived from contours of the ground, mossy logs and appropriately placed shrubs and ferns.

Some areas even have no plants except the trees that provide shade and a surface for moss to grow on. Such shady green spaces are a wonderful effect but it is not necessary that the entire garden be devoid of nonmosses.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, showy flowers and bright foliar variegation is avoided like the plague. Because most mosses are green, a moss garden is more about showcasing shades of green and visual textures. Bright colors are out of place and draw the eye and attention away from the cool mossy greens.

Flowers can still have a role to play within a moss garden, however. White-flowered aralias; green-flowered Decaisnea and red huckleberry; and small, purple, spring-blooming hepatica provide understated floral interest. Rather than draw attention from a distance, they are discovered up close, providing little “Oh, wow!” moments within the larger context of the moss garden.

Third, because flowers are deemphasized, nonflowering plants are encouraged. Ferns and conifers make up a significant portion of the nonmoss flora. The native deer fern (Blechnum spicant) is by far the most common.

Native sword fern (Polystichum munitum) and other planted nonnatives are a distant second. They provide interest on stumps; break up sharp borders between trails, rocks and moss; and create larger foliage islands in larger moss swaths.

This combination of design elements creates a peaceful, shady stroll that is easy on the soul. Our region is incredibly fortunate that Virginia and Prentice Bloedel, Richard Haag and Richard Brown designed this green treasure for others to enjoy. Moss gardens are an underused garden style and hopefully those who experience this garden might go create their own green oases.

Comments