The West Sound area abounds with people who enjoy aesthetically pleasing and interesting lifestyles. Perhaps no pastime is more enticing to all of the senses than baking one’s own breads and rolls in an age-old, traditional manner. Baking slow-rise artisan breads — in a brick oven heated with a wood fire built by hand, sometimes with the help of friends and family — must certainly be among the most satisfying of hobbies.

Sitting on a small knoll on Bainbridge Island, in a clearing surrounded by towering Douglas firs, are a home, guest house, garage and studio that look as if they were built by the same hands that created the iconic national park lodges and ranger stations in days gone by. Birds and butterflies flit among the flowers and vegetable plants in the well-tended gardens, and a sense of peacefulness — that this is how life really is intended to be lived — prevails.

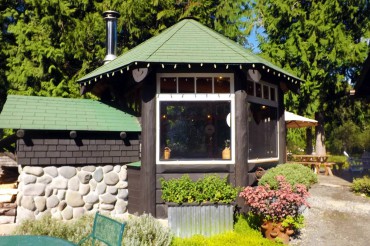

The reality is that Sweet Life Farm has only existed for 15 years. The buildings are new but were built and decorated in the tradition of western forest lodges. Owners Bob and Nancy Fortner have carved out a pleasing and productive life, living close to the land, appreciating the bounty of Mother Nature and baking bread for their own use in a beautiful brick oven that is housed in an enchanting log house.

A centerpiece of the farm, the bake house features a counter with bar stools, large windows, bright lighting and a fabulous sound system.

“The building is actually a gazebo designed by a Canadian log-home company, to which I added half-walls and windows,” Bob Fortner explains.

The air was filled with beautiful classical music the morning this writer visited, along with the fragrance of crackling fruitwood logs as the oven was heating.

Fortner bakes bread for his own family use and holds pizza parties when entertaining guests. Recently, he charmed Bainbridge Island Chamber of Commerce members with his baked-on-the-spot flatbread.

He built the oven himself, with help from friends. Fortner owned one previously at another location. That oven was built as a workshop project under the tutelage of Alan Scott, who for dozens of years was considered the quintessential brick oven builder. Scott travelled around the country helping to design and build all sorts of wood-fired, brick bread ovens for small families and large commercial operations alike.

Scott died in 2009 in his native Tasmania, but co-authored a book in 1999 with Dan Wing, “The Bread Builders: Hearth Loaves and Masonry Ovens,” which remains today an important resource for those wishing to build their own backyard bread oven.

An Artist’s Oven

Another oven, built about five years ago, is tucked into a cozy space between an art studio and the garden at the Olalla home of Rick Alway and Sharon Feeney. Alway built his oven himself, using the Wing-Scott book as his reference, as it contains complete plans and diagrams. He was inspired by an Italian woman he once knew who had a bread oven in her backyard.

Alway, too, has adopted a regular schedule of baking bread as a way of life. He has baked homemade bread since he was about 12 years old.

“I never tire of watching Rick handle the dough with an artist’s hand,” Feeney says, “as he turns and folds the dough in the kneading process and makes the little artistic slashes along the top of the finished loaf before baking.”

The slash, which gives each type of artisan bread its own character and the baker an opportunity to leave his own mark, serves an important function. Scoring the loaf just as it is ready to go into the oven controls how the loaf will rise and keeps it from tearing. Feeney, who is a stone sculptor, carved the keystone in the brick arch of the oven.

Personalized Touches

Don Heppenstall built his oven about three years ago, inspired by his daughter, who had previously built a cob oven. A cob is also a bread oven, used for thousands of years in many cultures and manufactured from mud, straw and sometimes other found materials.

Cob ovens are easy to build, but if not protected in the Northwest climate, they are very temporary, succumbing to the rigors of the wet weather. Heppenstall’s oven, about 43 inches in diameter, is a slightly different design than the Alway and Fortner ovens, which are about 4 by 5 feet, but it functions much the same way. It has an insulated door and can bake about 10-12 loaves at a time.

Although pizza can always be baked in a bread oven, bread cannot always be baked in a pizza oven. Many pizza-oven kits available on the market today do not retain heat long enough or consistently enough to bake good bread.

Initially, the Heppenstall oven was built as a pizza oven. But after his daughter gifted him the book “52 Loaves” by William Alexander, Heppenstall added three layers of ceramic refractory blanket and stuccoed the outside, including a personal touch with seashells and other decorative elements.

“With the insulated door in place, the exterior is never more than 90 degrees when the interior temperature can be as high as 750,” he says.

He notes that one feature that all backyard ovens require in this climate zone is a roof to protect it from the elements.

Baking Tips

The success of baking in a brick bread oven depends on making sure the temperature is hot enough and consistent throughout the entire baking space. The night before bread baking will take place, some bakers take advantage of preheating the oven with a hot fire, and bake pizza.

When baking pizza, the coals are pushed to the back and left inside the oven, and flame is usually present. Pizza baking requires a very hot environment, and a 650-degree temperature will bake a pizza in about three minutes, enabling a crowd to make their pizzas and cook several very quickly.

Once the oven bricks are heated through, the coals and ash are raked out, and the floor of the oven is wiped clean with a damp, cotton-fiber mop. At this point, the door is closed to allow the oven temperature to equilibrate, or mature throughout, and eventually cool to bread baking temperature of about 450.

Meanwhile, in the bakery kitchen, a slow-rise dough is developed, frequently utilizing a sourdough starter, or “levain.” Loaves can take 24 hours or more to rise to baking readiness using this method, but the extra time allows for the flavors of sourdough and grain to develop.

Every baker has his or her preferences as to the type of bread preferred but most lean toward healthy, traditional grains; whole grains and sustainably produced ingredients.

Fortner has found a source of locally grown flours that are processed by Shepherd’s Grain in Portland. He has a commercial, 20-quart mixer and produces about 20 loaves at a time. Alway likes to grind his own flours so he buys whole grain, most recently from Bob’s Red Mill, and does his kneading by hand. Heppenstall usually sources his flours on sale at the grocery store, preferring Bob’s Red Mill and Stone Buhr brands. He also prefers the higher proteins in bread flours, which translates to higher gluten content, resulting in better rise.

The ovens and methods of producing artisan breads are as unique as the owners and bakers themselves. The common thread that connects them is following the age-old tradition of baking on a hearth and sharing their successes with friends and family.

A source of continued learning and sharing with other bread bakers is the Bread Makers Guild of America. Fortner took an artisan bread-baking course sponsored by the guild and remains a member. Heppenstall participates in a group of foodie friends, “The Loafers,” who meet regularly to literally break bread and share a good time. Alway and Feeney share their oven with friends and groups they are involved in for social events.