Long before American ports became a major part of a burgeoning transportation industry — and before roads became as common as Northwest rain — Puget Sound was a bustling maritime throughway. The gateway to Puget Sound for all the ships too large to enter Deception Pass was Admiralty Inlet, where the Point No Point shoal was known as a hazardous spot.

Long before American ports became a major part of a burgeoning transportation industry — and before roads became as common as Northwest rain — Puget Sound was a bustling maritime throughway. The gateway to Puget Sound for all the ships too large to enter Deception Pass was Admiralty Inlet, where the Point No Point shoal was known as a hazardous spot.

When vessel traffic was expected to increase due to the extension of the Northern Pacific Railroad to Tacoma, the U.S. Lighthouse Board considered a beacon and fog signal critical to maritime safety at the shipwreck-prone Point No Point. With a $25,000 appropriation by Congress — and after various construction delays including extensive negotiations with the property owner — in 1880, the Point No Point Lighthouse became the first navigational beacon on Puget Sound.

Today, ships, both military and commercial, are still passing Point No Point to and fro, but the lighthouse is no longer a critical navigational aid. In fact, all the U.S. Coast Guard (which still owns the lighthouse) needs now is an automated light that is simply mounted on a pole.

Today, ships, both military and commercial, are still passing Point No Point to and fro, but the lighthouse is no longer a critical navigational aid. In fact, all the U.S. Coast Guard (which still owns the lighthouse) needs now is an automated light that is simply mounted on a pole.

But the lighthouse has remained a beacon, albeit these days for a different kind of traffic. As part of the Point No Point Park operated by Kitsap County, the lighthouse is a popular Hansville destination for locals and visitors alike.

The lighthouse is only available for tours during April through September (and by arrangement). The beachfront park, however, is open year-round, as is the one half of the old lightkeeper’s duplex, which is offered to the public as a vacation rental.

The lighthouse is only available for tours during April through September (and by arrangement). The beachfront park, however, is open year-round, as is the one half of the old lightkeeper’s duplex, which is offered to the public as a vacation rental.

“The appeal of lighthouses is inexplicable; they mean different things to different people,” says Jeff Gales, executive director of the U.S. Lighthouse Society, which is headquartered in the other half of the keepers’ duplex. “I think they move people and there’s a romantic nature to lighthouses.”

A visit to the Point No Point beach feels a bit like traveling back in time. Taking in the serene atmosphere, it’s easy to forget the need to finger the smartphone or dash into highway traffic for that next hasty errand. Visit at a less popular time, and nothing much disturbs that tranquility but the cry of seagulls or the occasional beach walker.

It’s this type of scenery that attracts people like Susan and David Bula. The Spokane couple was enjoying a stay recently at the keepers’ duplex. The pair had just gone through some stressful series of events.

It’s this type of scenery that attracts people like Susan and David Bula. The Spokane couple was enjoying a stay recently at the keepers’ duplex. The pair had just gone through some stressful series of events.

“Coming here to this beautiful place and peaceful atmosphere was the perfect thing under the circumstances,” David Bula says.

The Bulars, who are members of the U.S. Lighthouse Society and consider lighthouses their go-to vacation spots, are also passionate about fire lookouts.

“Lighthouses are similar — they’re being neglected because technology got better,” Susan says. “We feel the need to preserve something so beautiful.”

A Kitsap County Historic Treasure

Kitsap County began leasing the Point No Point property from the Coast Guard in 1998. In order to create public access to the lighthouse itself, the county created a volunteer docent group. From this group was born the Friends of Point No Point Lighthouse nonprofit, which continues to provide volunteer docents for the tours and is now a chapter of the U.S. Lighthouse Society.

In 2008, the Lighthouse Society moved its headquarters from downtown San Francisco to Point No Point, taking over the management of the entire light station — which includes the duplex, the lighthouse building (with a fog-signal room and the historic lens tower), an oil house and the old keepers’ workshop that is now home to a gift shop.

The society, whose focus is on preservation, obtained funding to restore the station. The renovation of the lighthouse building brought back some of the historic architectural features and colors.

“We had to decide on an era to restore the building to, because it had changed over time,” Gales says. “We decided to go with the era when electricity was brought to the station in the 1930s.”

A few artifacts inside the former fog-signal room harken back to the earlier days. Among them is the diesel engine for one of the foghorns. The use of the fog signal was discontinued here in 2012, and is being phased out of lighthouses nationwide.

A few artifacts inside the former fog-signal room harken back to the earlier days. Among them is the diesel engine for one of the foghorns. The use of the fog signal was discontinued here in 2012, and is being phased out of lighthouses nationwide.

“There have been many incarnations of the fog signal over the years,” Gales says. “Each signal sounded different.”

The first fog signal used by U.S. lighthouses was a cannon, later replaced by a bell (frequently rung by hand). The fog signal had been powered by various methods through the years, from clockwork-like mechanisms that used a weight, to horses, tidal motion, oil engines, and steam-powered engines with either wood or coal. Eventually, the horns became electric.

At Point No Point, the first fog bell was made of bronze and weighed 1,200 pounds. It was cast in Philadelphia and used the clockwork mechanism powered by descending weights. The mechanism had to be rewound every 45 minutes during fog — and the keepers weren’t strangers to the hammer, as the mechanism was prone to breaking and the bell had to be struck by hand.

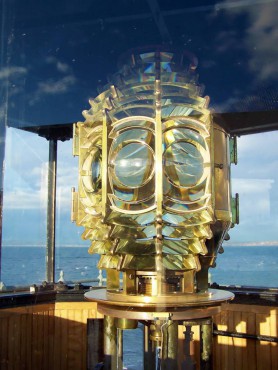

The historical lens, no longer functional, can only be reached by climbing a tall, narrow staircase. The cozy tower, not accessible to the public, has new windows with special UV glass to protect the lens.

The rotating Fresnel lens still has a door for an oil lamp, which was eventually replaced by a light bulb. The Fresnel lens is designed to refract and reflect the small amount of light and create a powerful light beam.

The lens, invented by French engineer and physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel in the 1820s, had been used in Europe for nearly two decades before making its way to America. The U.S. Congress finally decreed in 1851 that all new lighthouses and new lighting apparatus must use the Fresnel system and by the end of that decade, all U.S. lighthouses but two were converted.

In those days, each light had different characteristics, such as flashing intervals. To navigate, sailors used a light list — the first true one was issued by the Treasury Department in 1839, and 30 years later, the U.S. Lighthouse Service began publishing an annual one.

“The sailors always knew where they were because of the lighting characteristics notated in the light book,” Gales says.

The Point No Point Fresnel lantern was permanently switched off in June 2006. An automated optic light, secured inside a plastic case on a rail outside the lighthouse, beacons instead — flashing three times every 10 seconds. The modern lights, while still being used as navigational aids, no longer have distinguishing characteristics, thanks to the ships’ use of more advanced technology like GPS.

The era of manned lighthouses spanned around 300 years before they became historic treasures rather than important navigation aids. More than two decades ago, a lighthouse preservation movement began growing, boosted in 2000 by the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act.

Much like life-saving stations and netsheds, lighthouses have become the landmarks of yesteryear — treasured reminders of the country’s maritime heritage. The Point No Point Lighthouse has certainly ensured that Hansville — perhaps the entire Kitsap County — will always remain a significant entry in the history annals of Puget Sound.

Sources for historic information for this article and the historic facts sidebar include the U.S. Lighthouse Society (uslhs.org), Friends of Point No Point (pnplighthouse.com), the U.S. Coast Guard (uscg.mil), "The Coast Guard at War" ("Aids to Navigation," Volume XV, published by USGS in 1949), "United States Lighthouse Service 1915" (published by Washington Government Printing Office in 1916) and USLS Executive Director Jeff Gales.

Comments