The colorful posters with a collection of common herbs are a popular social media share. Save the bees, they say; plant these. I’ve been known to peek at those lists and note to myself — I could use a few more hyssop plants in my apiary — but that well-meaning call to action widely misses today’s challenge of how to best help pollinators.

The colorful posters with a collection of common herbs are a popular social media share. Save the bees, they say; plant these. I’ve been known to peek at those lists and note to myself — I could use a few more hyssop plants in my apiary — but that well-meaning call to action widely misses today’s challenge of how to best help pollinators.

In case someone has missed the memo, pollinators in general are struggling. Pollinators are nature’s matchmakers, working together with plants — in many cases interdependent — to ensure the plant’s reproduction. In exchange for matchmaking services — moving pollen, the male plant essence, to female plant organs — pollinators are enticed with flower nectar, which is carbohydrate flight fuel; and pollen, a source of protein or food.

Pollinators need plants; their future is intertwined with having a wide variety of pollen and nectar sources. If we want to help one, we need to address both.

Here are 10 things we can all do to successfully plant for pollinators.

1. Be Kind to Soil

Most of us pick up a bag of topsoil at our local garden center and call it good, but soil is so much more than that. There are millions of different mycelium and minuscule creatures living at varying soil temperatures and conditions — something like one tablespoon holds more living forms than people currently populating Earth.

And not all plants survive in the same kind of soil, regardless of what you see online. Some plants will only thrive in very specific growing conditions, such as tree bark. I remember my father watering Cattleya orchids barely hanging on to the side of South American trees in our backyard in Brazil.

Soil, in general, is 45% rock, 25% water, 25% air and 5% decomposing organics with living organisms. Unless you’re trying to garden on a Missouri limestone hillside as I do, then you’re growing primarily rocks and your pickax is exquisitely speeding up the soil-making process. Soil is not renewable. It takes 300-400 years to renew existing soil and 2,000 years to “make” new soil. Well, 1,999 years in my garden; I use two pickaxes.

2. Recycle Food

We waste about 40% of the food we buy, so why not recycle it? Two parts brown or dried food to one part green. Add water. Toss and let decompose in a dark container until black and crumbly. Mix with existing soil to feed soil microorganisms and plants. Don’t call it composting. For some reason, that is too complicated for some people and it doesn’t have to be.

How to start? Add a plastic bag to your freezer bin and toss leftovers in there. When full, take it outside and bury it in a flower bed to feed your soil residents, keeping plants healthy. You’ll be in a small composter in no time.

3. Collect Rain

Most of us have gutters on our houses; it’s a simple tweak of a spout and a hardy receptacle of some sort, and you can collect rainwater. I know the potted plants on my decks prefer rainwater to the treated city water I sometimes have to use to keep them hydrated.

Repurposed 55-gallon totes make handy water storage containers and a simple sump pump can help deliver the water where you need it. Harness what is already getting delivered through a gutter system instead of letting the water wash away precious soil.

Living in a smaller space? Add a bird bath to a corner. Let it collect rainwater and keep it full through the growing season.

4. Reduce or Eliminate Turf Grass

We have the equivalent of the state of Texas in planted turf grass in the USA, an expensive lawn covering that is expensive to establish and maintain, with no redeeming quality as far as the ecosystem is concerned. Luckily there are alternatives being developed that still create a green expanse with low-growing flowering plants and can provide pollinators with food and flight fuel.

5. Know Your Pollinators

5. Know Your Pollinators

Well, yes, we love the pollinator poster child, the monarch butterfly. Some even try to hand-raise them, but studies show if you want to help monarch butterflies, best to plant native milkweed for them.

How about flies, bats and wasps — they are also specialty local pollinators unique to an area. And we’re only too happy to try to get rid of what we don’t understand.

Take tomato hornworms, the bane of most tomato gardeners. And yet that hungry caterpillar turns into a lovely hawk moth, a nocturnal pollinator. I keep my tomato hornworms fed by moving them to one tomato plant. I separate it from the rest and, once the caterpillars disappear, the tomato plant regrows leaves and gets to spend winter inside with me. And both the hornworms and I get something to eat. Take a step back and rethink some of those bad habits. And question some of the native lore about what is, or isn’t, good in our gardens.

6. Welcome Birds

Instead of using pesticides, hang birdhouses. Some 60% of all birds depend on caterpillars and undesirable garden bugs for baby bird food. When we drop a can of pesticide on that wasp nest in the deck corner, you know you’re going to miss and, in the process, contaminate your own living space with harmful chemicals.

Instead of overusing chemicals, focus on encouraging birds into gardens; you may be surprised at who else moves in. Here are some additional ideas for creating a bird-friendly garden.

I’ve found my 50-plus birdhouses on my one acre hosting lizards, tree frogs, wasps and yes, a small black snake. These are all desirable garden residents, each with their own meal preferences.

7. Use Decoy Plants

There are also plants that work well as decoys. Delicious nasturtiums, for example, are not only edible by us, but aphids like them, too. Plant nasturtiums to decoy aphids from tender vegetables such as cabbage and to protect roses. I use them in hanging baskets so I can easily move them around for their bug patrol.

8. Embrace Natives and Nativars

Not only are some pollinators unique to a particular location, but so are the native plants that depend on them. Native trees, shrubs and flowers have evolved intricate relationships with native pollinators that other plants can’t fill. If a plant is not available, then the pollinator can’t thrive or survive.

Remember the big push years ago to plant for monarch butterflies? Someone forgot to mention not to plant tropical milkweed, which was keeping monarchs from migrating south before the weather turned cold. By focusing on planting native milkweed plants instead, the native plants not only had a limited blooming period, but the end of their blooms signaled to the monarchs it was time to keep moving south.

9. Keep Planting

Rethink that open space you have and put it to good use by planting native trees. Trees will by far provide the most flowers per square inch and native trees will do well planted in their native soil and growing conditions.

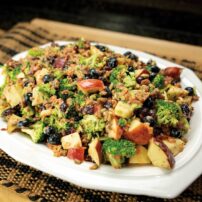

Incorporate a raised bed for favorite vegetables and let native flowers growing nearby entice pollinators to increase your food yield.

As more land is taken out of native habitat and turned into housing, we need to compensate by planting more on what land remains.

10. Choose the Right Time

You can have the best combination of soil and plant species, but if the time isn’t right for the plant, nothing is going to happen. Plants focus on reproduction when their surrounding conditions are supportive — sunny, windless days with temperatures between 74 F and 86 F. It’s like getting ready for a date — the plants want excellent conditions so they can focus energy on regenerating. When temperatures start to head north of 86 F, plants shift from reproduction to survival.

Know what the temperature trends are in your area and identify the most likely best times for your plants to reproduce. That’s when they will attract pollinators with a range of sweet nectar.

Respecting Our Pollinators

After years of lecturing about planting for pollinators and more than a decade of keeping bees — both native and honeybees — I can’t pass by manicured, green-turf-covered lawns with a dot of shrubs and not feel sad. We need to rethink our aesthetic of garden beauty.

Our gardens are someone’s home and should be shared with other creatures. We should strive for balance, not perfection. Our healthy gardens are a busy place with bugs on flowers, birds flying overhead and insects moving across the soil, each with their own food source and nesting needs met.

We may be a bit spoiled thinking our food comes from grocery stores, but the variety of foods we are lucky enough to enjoy are courtesy of pollinators.

Comments