The last tent caterpillar outbreak in West Sound happened quite a while ago. Yet the memories — of the sounds they made as they munched away at our tree canopy and the shivers they sent through my spine as they fell on my head or crunched underfoot — have not diminished all that much over the years.

They make their appearance cyclically, though not as regularly as the cycle of every seven years that you have probably heard about. I have seen a few individual caterpillars in my own garden this year, several tents in a client’s apple trees in the center of Bainbridge Island, and quite the outbreak on the Northern tip of the Kitsap Peninsula, covering the shrubs at the Point No Point Lighthouse Park.

Bellingham was hit hard last year, but I had a hard time finding healthy caterpillars there just a week ago.

The tent caterpillar population in Kitsap County seems to be building, and I expect we will see quite a few of them next year.

What can you do to keep their hungry numbers in check in your own garden?

Before you read on, know that sitting on your deck and doing absolutely nothing will be almost as effective as following some of the advice I include below. Nature is a beautiful thing, and if left alone, has developed an amazing arsenal to keep these pests in check.

My advice would be to protect only those trees that are small, struggling or overhanging the said deck and the lunch you are about to enjoy.

Life Cycle of the Western tent caterpillar (Malacosoma californicum pluviale)

Egg –> Larva –> Pupa –> Adult

Every life stage calls for a different approach for control.

Egg

The egg masses of the Western tent caterpillar appear by August and resemble dark, dense foam encasing the tips of branches of their favorite trees like plums, apples, alders, willows, birches and ash. The egg masses are a few inches long and can be scraped off or pruned out during the fall and winter.

The WSU Extension recommends leaving the egg masses nearby so any natural predators in the eggs can emerge (Trichogramma parasitoid wasps lay their eggs directly into the eggs).

Larva

This is the life stage we are most familiar and concerned about.

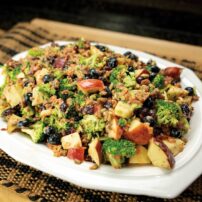

The hairy caterpillar, about 2 inches long and sporting a white line down the middle of the back with two yellow spots on each segment of the body, is a ravenous creature that can defoliate a tree if in sufficient numbers.

The larvae emerge in early spring and start building their web to protect them from the elements. Prune out the affected branches early in the morning, before the caterpillars leave to feed. You can submerge the branches/webs in a bucket of soapy water (I found a tablespoon of dishwashing liquid in a half-full 5-gallon bucket effective).

You can also place the webs in a garbage bag and stomp on them. Avoid burning them for safety reasons.

Before you destroy any larvae, however, look them over. Look for white spots on their heads or bodies (eggs of parasitoid fly larvae), or caterpillars that are lethargic or disfigured (Ichneumonid wasp parasitoids already feeding inside the body, bacteria, viruses).

Do not destroy these afflicted caterpillars! Nothing we can do will be as effective as these natural predators and diseases.

There is an effective biological control you can use, Bt, or Bacillus thuringiensis, but only while the larvae are small and actively feeding. Follow directions carefully and be aware that this bacterium will infect other caterpillars as well, so use sparingly. The product has a limited shelf life.

Pupa

The larvae form cocoons that are white and often dusted with yellow grains over the months of late June and July.

Adult

The adult form is a brown moth with two transverse lines on their wings. These emerge in summer and are eaten by birds and bats.

Isn’t nature fantastic? If left to its own devices, these pests, like many others, will be kept in check by their natural predators and diseases.

Comments