Henri Matisse. If one has ever visited the Matisse Chapel in Vence, France, the first, perhaps most important element that overcomes a visitor is the light. Prisms embrace morning yellows and blues and become rainbows across the altar and flooring, resulting in a magical, mystical, spiritual experience. Exactly what the artist wanted.

Artists are obsessed with light and some, especially abstract artists, study clouds, sunsets, the way shadows change on mountains or water for influence. They recognize how the light changed ideas for the work and how light can capture the sculptural element of a canvas.

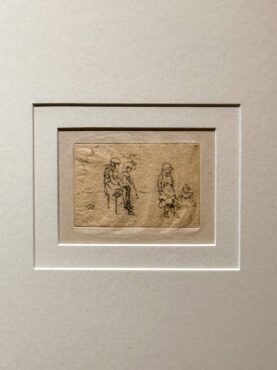

Most people don’t think of two-dimensional work (paintings) as sculpture. Painters do. Some art collectors, while rare, do. With this in mind, Brian Scott of Illumina Design in Silverdale began working with a north Puget Sound client to reflect the love, interaction and joy the client gets with every work in his collection. This collection is not just a grouping of paintings or sculptures; it’s a life story that celebrates graduations, marriage, sorrow, humor and the humanness of being. It’s also an extraordinary collection encompassing 18th and 19th century masters, from the midcentury Northwest School, to midcentury California figurative expressionists, to living contemporary artists.

Unlike many homes with exceptional collections, this client’s home is, well, a home. There are binoculars on a table, a bit of paper on a desk; Molly, the cat, wanders for a scratch, and Bruce, the dog, clamors for attention. Books are happily opened, partially read; banjos line another room waiting for attention; and yes, that’s a Chihuly on a table in the beautiful room overlooking north Puget Sound.

Artists want their art to be cherished, loved. If there were an artist “club” for collectors, they would all be sitting around smiling.

The client is a scientist. But his family was entrenched in the arts. His mother was a painter, and his father was an established San Francisco Bay Area art dealer. In his younger years, he grew to know, appreciate and love art. He and his late wife amassed a substantial collection of work, upon which they remodeled their home.

The client is a scientist. But his family was entrenched in the arts. His mother was a painter, and his father was an established San Francisco Bay Area art dealer. In his younger years, he grew to know, appreciate and love art. He and his late wife amassed a substantial collection of work, upon which they remodeled their home.

“It used to be a bed and breakfast,” Scott explained. “My client did not want a hotel; he wanted a home for his art. It had to be able to house his art.”

This was a project of love and devotion. There is the late wife’s sewing room, which is outfitted with sewing machines for intricate design, as well as pictures of playful but gorgeous period costumes that she had handsewn. There is the client’s study, which has a side room for tying fishing flies (one of his hobbies) and a beautiful ceramic sculpture of a brain — of course, anatomically correct. Connecting both suites is a lovely balcony overlooking the Sound.

This was a project of love and devotion. There is the late wife’s sewing room, which is outfitted with sewing machines for intricate design, as well as pictures of playful but gorgeous period costumes that she had handsewn. There is the client’s study, which has a side room for tying fishing flies (one of his hobbies) and a beautiful ceramic sculpture of a brain — of course, anatomically correct. Connecting both suites is a lovely balcony overlooking the Sound.

The couple were more than art collectors or avid travelers. They were inquisitive, constantly seeking information and questioning all they experienced. They also had a sense of humor and (apparently) liked to play tricks on their guests.

This is evident in the joke of Zachary, the zebra, who jumps out to a visitor from seemingly nowhere as one goes up the drive. He is hidden in the grasses — and poof! There he is! The owner laughed when asked who the artist was, saying, “It was fiberglass, and I painted its stripes.”

But then, the visitor turns a corner to encounter a stunning black granite Preston Singletary totem, maybe 12 feet high, nestled into its garden like it has been there forever, overlooking the Sound.

It was a project to redo a guest room that connected Scott to his client. One of the client’s neighbors is an interior designer who knew Scott. She took him to Scott’s own home, which serves as a “performance lighting studio,” and the client was intrigued.

“Lighting can change mood, warmth and texture, and when I had the chance to design the lights for this wonderful home, it was exciting,” Scott said.

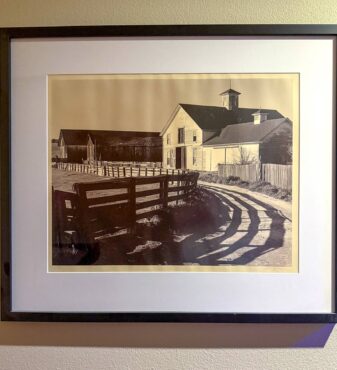

Performance lighting is, well, technical. It’s like theatrical lighting but programmed for a home or professional setting. Each fixture in the house is programmed to a specific frequency to bring out the overt or subtle textures and hues of a painting. Most museums or art galleries don’t have such lighting with a touch of a switch.

“When we looked at the collection, we wanted to make sure his lighting was perfect, matter not the time of day,” Scott explained.

This means that with the home’s expansive windows, the lighting in the house will change as natural light from the outside changes through the day and seasons.

This means that with the home’s expansive windows, the lighting in the house will change as natural light from the outside changes through the day and seasons.

Most people have an “on-and-off” switch on their lights. But this home has one that, if you push it, the entire house goes on or off. It can welcome visitors in the evening or shut off all at once to allow the client to go to sleep and tuck in with Molly and Bruce.

For the client and his visitors, the lighting in the evening is magic. He can change the lighting to bring out aspects of various works. Art can be a friend. It can be comfort. “I love wandering around talking to the art and seeing how it responds, especially with Brian’s lighting,” the client explained. His happiest moments, it seems, are when he plays with the art.

For example, there is a magnificent cast glass piece by Ann Wolff, whose three-dimensional work plays against itself to create multiple images of the same form using mirrors and light to capture spirit and soul. It sits on a pedestal adjacent to a Puget Sound view window. In the day, it reflects the changing shadows of east light. In the evening, it becomes more than cast glass. It becomes a visual poem. He delights, “Isn’t it just marvelous?”

For example, there is a magnificent cast glass piece by Ann Wolff, whose three-dimensional work plays against itself to create multiple images of the same form using mirrors and light to capture spirit and soul. It sits on a pedestal adjacent to a Puget Sound view window. In the day, it reflects the changing shadows of east light. In the evening, it becomes more than cast glass. It becomes a visual poem. He delights, “Isn’t it just marvelous?”

This is to Scott’s credit. Every piece of art is programmed into a tablet. Each work has its own setting. Each is programmed for specific hues, texture and contour. It brings out the brush strokes, the underpainting, the layering, the reasoning of an artist’s intent. With the flick of a switch, Wolff’s sculpture can be exhibited in blue or red hues or the cold, clear color of glass ice.

Achieving this wasn’t easy — this home was built as a bed and breakfast, subject to commercial building construction. Ceiling joists were closer together than in a “normal” house. “We had a lot of engineering to do to get the lighting to fit correctly for each work,” Scott said.

With each fixture specifically programmed, the client can change any hue or light intensity. And should he want to move art around, the lighting requires reprogramming.

With each fixture specifically programmed, the client can change any hue or light intensity. And should he want to move art around, the lighting requires reprogramming.

He can move the light to reflect brilliant light or just to black and white. He can take a stunning Miro from primary colors to gray. He can make a Guy Anderson painting reflect the rich reds the artist intended or suddenly reflect deeper browns and brushstrokes.

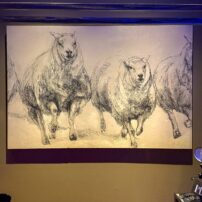

For an artist, the light frequency changes can bring out what makes the art jump — those brushstrokes or intentional layering of paint with the palette knife. The work of Janna Watson is a stunning example. Her gorgeous paintbrush imprints are firmly implanted against the black background, creating a whirl of color and illusion.

Over the fireplace is a work by midcentury California painter Joan Savo. It’s a lovely abstract figurative work illustrating the midcentury push to go beyond the masters of earlier generations of, say, Picasso or Dali, to make painting speak in a sculptural sense and resonate with the musical, contemporary compositions of the midcentury era — think John Cage or Philip Glass. The painting is oil, with lots of brush and palette knife layering. The figure jumps to life under Scott’s lighting; it becomes three-dimensional, speaking to the viewer. Yet, again, this painting is at home. Quiet. Above a fireplace. It’s not in a museum. It’s a greeting to its owner: “Good evening. Hi. How are you?”

And this art collector responds, in his nightly interactions with the art, “I just wander and want to know where the next place the art will take me, what it will reveal.”

Isn’t that what art should be? Unveiling new places yet to be discovered?

And with Brian Scott’s lighting, isn’t that the magic of technology?