Walk into Wayne and Anne Blair’s Poulsbo bungalow and it could be 1918 rather than 2018.

Walk into Wayne and Anne Blair’s Poulsbo bungalow and it could be 1918 rather than 2018.

True to the aesthetic of the Arts and Crafts era, their home features a river-rock fireplace with a mantel shelf made of old-growth maple; stone countertops and tile backsplashes; wood doors and trim throughout; three-over-one window sashes that frame the landscape outside; and a wide, inviting porch with river-rock columns.

The interior is furnished with antiques inherited from Anne Blair’s grandparents. Artwork includes a painting of their former longtime home by an artist-prodigy grandson, whose use of color resembles that of noted Tsimshian artist Roy Henry Vickers.

“Your house looks like it’s been here forever,” neighbor Krista Brooks told the couple during a recent visit.

The Blairs’ home was actually finished in April this year and is one of what will be 32 homes in Snowberry Court Bungalows, a neighborhood next to the Poulsbo Municipal Cemetery on Caldart Avenue.

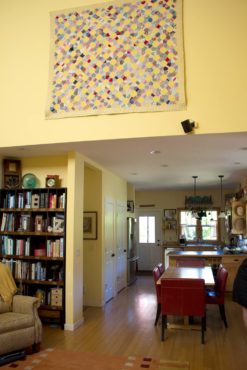

The Blairs downsized from a 4,000-square-foot home on Bainbridge Island to this 1,900-square foot, 1.5-story bungalow but due to the craftsmanship and efficiency in design associated with Craftsman-style bungalows, they don’t feel squeezed. (Because of the open-floor plan and windows, the line of sight extends from one end of the house to the other and to the outside — a Craftsman principle of bringing the outside in.)

“There’s something about the aesthetic, the sense of functionality,” said Anne Blair, a former Bainbridge Island mayor. “I like the size. It feels welcoming.”

The neighborhood was the vision of developer Holly White, who was inspired by visits to a neighborhood of Craftsman bungalows in Pasadena, California; by the designs of architect Susan Susanka; and by her own experience of growing up in a close-knit neighborhood where neighbors watched out for each other.

Many of the Snowberry bungalows resemble the Pomona model of Craftsman homes offered by Aladdin Homes in 1920 and contain many of the features that made the Craftsman style so enduring. Some of these features include low-pitched, gabled or hipped roofs; partially paned doors; large, covered front porches with tapered support columns resting on massive stone or brick piers that extend to ground level; combinations of board-and-batten and shake siding, or horizontal lap siding and shake siding; earthy, neutral paint colors; built-in cabinetry and large fireplaces, some with built-ins on either side; wooden windowsills and frames; crown molding and thick baseboards; extensive use of stained woodworking; and master bedroom and bathroom on the main level.

Many of the Snowberry bungalows resemble the Pomona model of Craftsman homes offered by Aladdin Homes in 1920 and contain many of the features that made the Craftsman style so enduring. Some of these features include low-pitched, gabled or hipped roofs; partially paned doors; large, covered front porches with tapered support columns resting on massive stone or brick piers that extend to ground level; combinations of board-and-batten and shake siding, or horizontal lap siding and shake siding; earthy, neutral paint colors; built-in cabinetry and large fireplaces, some with built-ins on either side; wooden windowsills and frames; crown molding and thick baseboards; extensive use of stained woodworking; and master bedroom and bathroom on the main level.

The Arts and Crafts bungalows were designed to be energy-efficient as well, and the Snowberry bungalows follow that principle. The neighborhood is built on sloping land looking toward the Olympic Mountains; windows, breezeways, patios and porches capture cooling breezes even during summer. Walls and roofs are built using insulated panels, a newer technology but one following the Craftsman focus on efficiency. Each home has a tankless water heater, which heats water only when it’s needed.

“It’s so easy to live here,” Anne Blair said.

An Enduring Style

Poulsbo’s emergence in the 1880s coincided with the emergence of the Arts and Crafts movement. The movement was a reaction by proponents against what they saw as a decline in standards amid Industrial Age factory and machine production. The thought: simplicity rather than excessive ornamentation, craftsmanship rather than mass production, and natural rather than artificial materials. The result: Craftsman homes were practical yet beautiful, and were built to last.

However, few Craftsman homes from the late 1800s to early 1900s remain in Poulsbo. Constant change brought as much alteration to the design of local homes as it did to the landscape.

Some background: This area was originally part of the homeland of the Suquamish Tribe, which signed an 1855 treaty ceding land to the United States and making it available for newcomers. Available land sparked a wave of Scandinavian immigration that began in the 1880s; newcomers came from the Midwest and from Norway, drawn by opportunities to log, farm and fish, as well as surroundings that reminded them of their ancestral lands. Logging and farming altered the landscape.

The population boomed and diversified in the 1940s, as Navy bases in nearby Keyport and Bremerton ramped up for the war effort. Nondescript homes went up to accommodate thousands of new families.

Postwar, construction practices followed the trends of the day. Streams were undergrounded to accommodate development. Farms gave way to subdivisions. A hilltop forest was cleared for big-box stores. An auto row came and went. Homes built at the end of the 20th century reflected the trend toward larger homes. Neighbors were separated from each other by fences.

A stroll from downtown to the city’s oldest established neighborhood will lead you to well-preserved heritage homes in what is called Old Town. But elsewhere in the city, homes reflecting the timeless beauty, values and lifestyle of the Craftsman era are few.

White wanted a design that would outlive the trends. In the Caldart Avenue/Lincoln Road area, once part of a farming community known as Lincoln, only three early 20th century Craftsman bungalows remain: a 1,630-square-foot home built in 1904, a 1,399-square-foot home built in 1916 (with a barn built in 1918) and a 2,043-square-foot home built in 1920.

White wanted a design that would outlive the trends. In the Caldart Avenue/Lincoln Road area, once part of a farming community known as Lincoln, only three early 20th century Craftsman bungalows remain: a 1,630-square-foot home built in 1904, a 1,399-square-foot home built in 1916 (with a barn built in 1918) and a 2,043-square-foot home built in 1920.

Thanks to White, the Craftsman-style bungalow returned — and with it, a lifestyle common to other Craftsman communities, like the Fairmont Historic District in Fort Worth, Texas; the Craftsman Heights neighborhood in Pasadena, California; and the Ladd’s Addition neighborhood in Portland, Oregon.

White, who owns Bainbridge Island development company Snowberry Enterprises, believes the Craftsman style will continue to endure because of the cost-effectiveness, the efficiency and the ease of living it affords.

At Snowberry, front porches face either a courtyard or a park-like ground with apple, pear and plum trees from which neighbors can harvest. Gardens are fragrant with rugosas, and open spaces are planted with native and low-maintenance landscaping. Kinnikinnick, also known as bearberry, is a predominant groundcover.

Stone-and-wood benches on overlooks provide a view of the Olympics and the changing sky. Stormwater is filtered by bioswales that wind down to a long, shallow infiltration pond landscaped with dogwood, native serviceberry, Nootka rose, Oregon grape, shore pine, snowberry, strawberry bush, vine maple and willow.

“If you’re out on your porch, you’re going to have visitors,” Brooks said. “That’s part of the appeal of this neighborhood. This is like it was when I was a kid.”

Neighbors host progressive dinners at Christmas, meet-and-greets for new residents, work parties, a neighborhood garage sale and a croquet tournament.

Brooks’ husband, Pat, said, “When somebody needs something, there’s always someone to help.”

He recalled two occasions when his garage door didn’t shut because something was in the way of the sensor. Each time, a neighbor called him — once at 1 in the morning. “That’s going above and beyond,” he said.

White said porches and courtyards promote a sense of community. “That’s a huge part of the concept — people looking out for each other,” she said. “I loved the concept of the courtyard being the focus of the neighborhood.”

‘I Feel Like I’m Cuddled’

The Brookses were searching for a home to purchase in 2009 and didn’t connect with the tract homes and fixer-uppers they saw on the market. Driving around, they happened upon Snowberry Court Bungalows and were hooked.

Their home is one of two with a vaulted ceiling in the living room. “We selected this option because we wanted more height,” Pat Brooks said.

There are no hallways and, with the master bedroom and bath downstairs and all spaces easy to navigate, “it’s a good place to age in place.”

Bonnie Goodwin has been staying, with her husband, upstairs at the home of Dianne Iverson, who once lived at Snobwerry Court but is currently renting her home. The Goodwins are remodeling their own Craftsman home, in Suquamish. Goodwin said the layout of the Iverson home gives her and her host their own spaces — for the Goodwins, it’s a straight shot from back door to the stairs to second floor; Iverson has the entire first floor uninterrupted, although the three usually meet and visit in the kitchen.

“It’s very streamlined and easy to live in,” Goodwin said.

The Iverson home was Snowberry Court Bungalows’ first, completed in 2008. True to the Arts and Crafts aesthetic, this home interior features stained wood floors, doors and trim; casement windows that frame the natural world outside; tile backsplashes; a slate-and-tile fireplace; wood furniture and Tiffany-style lamps; and objects reflecting Iverson’s childhood in Japan. All that’s missing is a Yoshiko Yamamoto block print.

Iverson appreciates the quality of detail in her Snowberry home — the warmth of wood, the inviting front porch, the feeling of being “cuddled.”

“It’s not too big. It’s intimate,” she said. “It’s a comfortable place to be.”

Richard Walker is an independent journalist who lives in Poulsbo.