In the historic community of Grapeview, it can be hard to find your way around the first time you visit. Lots of tiny dirt roads finger off from the main road, featuring funny names that are often nearly identical.

In the historic community of Grapeview, it can be hard to find your way around the first time you visit. Lots of tiny dirt roads finger off from the main road, featuring funny names that are often nearly identical.

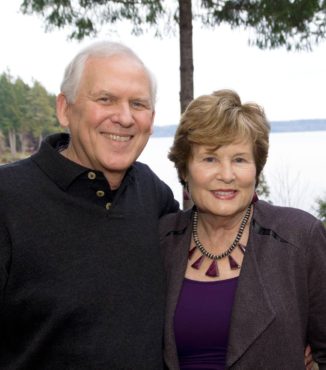

It nods to the legacy of each independent, pioneering settler, starting with the first homesteader, Lambert Evans. And that’s just fine with Margaret Campbell and her husband, Edward Johnson. Their recently completed home lies along a shoreline first selected by her great-uncle and reflects a century-old legacy of love, life and learning along Case Inlet.

“My great-uncle hired a fellow to row him around the bay,” Campbell says, circling her arms over the view from their home to the bay. “He was a judge in Tacoma and came here looking for a summer retreat for his family.”

“He looked for four key things,” Campbell explains, her reverence for her ancestor easily apparent. Thankfully, these criteria he kept in mind as he scouted the shoreline proved enduring qualities that kept Campbell, her sister and their entire family returning for generations beyond.

“He wanted a beautiful vista to Mount Rainier, an artesian well, good drainage and sun shining on the property every day of the year, or at least whenever it comes out from behind the clouds,” she says with a laugh.

The initial boundary included 64 acres. Later, he added almost 10 more acres that became the site of the McLane School and then, the Stadium School, from 1911 to 1918. That property included the school structure and a two-room teacher’s quarters located next to the schoolhouse.

The initial boundary included 64 acres. Later, he added almost 10 more acres that became the site of the McLane School and then, the Stadium School, from 1911 to 1918. That property included the school structure and a two-room teacher’s quarters located next to the schoolhouse.

Soon a widower, her great-uncle lived there every summer with his two daughters, who named the place Huck Farm; its name still remains today. Each year the family visited, they would hold a summer retreat and family reunion of sorts that grew, over the years, to include Margaret and her sister.

“My sister and I felt such a connection to this land,” Campbell says. “It was a happy time for us and held such great memories that we continued to vacation here, even as adults.”

“My sister and I felt such a connection to this land,” Campbell says. “It was a happy time for us and held such great memories that we continued to vacation here, even as adults.”

After Campbell and Johnson married — a second union for both — the couple would also visit. So, naturally, whenever they considered where to live following retirement, their peaceful Huck Farm kept coming to mind.

“We lived and worked in Washington, D.C., so our urban friends would ask us, ‘Do you not want to be near people?'” Johnson says, laughing.

Campbell most recently worked as a senior scientist for the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research. Johnson worked with the international consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, where, among other things, he did projects for the Department of Homeland Security.

Campbell most recently worked as a senior scientist for the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research. Johnson worked with the international consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, where, among other things, he did projects for the Department of Homeland Security.

“This land has always been our spiritual home,” Campbell explains. “As a blended family, we didn’t have a house where we’d raised our kids, so we wanted to create this as a retreat for everyone we love.”

Trying to do it all long distance, the couple went through a few architects. “We had a great architect back in Washington, D.C., but he didn’t have a feel for the property,” Johnson says. “The designs were just too modern and didn’t fit the landscape.”

“The whole process took about nine years,” Campbell adds. “And, while we definitely had our ups and downs, it was worth it.”

“The whole process took about nine years,” Campbell adds. “And, while we definitely had our ups and downs, it was worth it.”

During that time, they had the property designated as a historical site, and she points proudly to the bronze plaque standing at a charming point near the water.

Finally, one day, a question from a colleague of Campbell’s brought focus to their efforts. “She asked, ‘Why don’t you just build on the site of the old schoolhouse? It was probably placed there for good reason.’ And I thought, well, why not?”

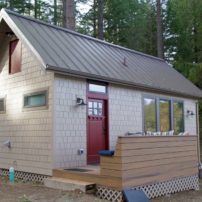

From the old structure, only the foundation and basement were salvageable; time had taken too much of a toll. However, after architectural designer Tami Selby brilliantly discovered that they could expand to the south of the original structure, she added space for a window-filled kitchen, butler’s pantry, laundry room and guest bath, as well as a shared office for the couple.

From the old structure, only the foundation and basement were salvageable; time had taken too much of a toll. However, after architectural designer Tami Selby brilliantly discovered that they could expand to the south of the original structure, she added space for a window-filled kitchen, butler’s pantry, laundry room and guest bath, as well as a shared office for the couple.

Campbell and Johnson declared it perfect and plans were approved, with construction crews breaking ground in late April 2015.

Still, planning the interior on her own proved daunting for Campbell. “We had a pretty grueling schedule and also made time to travel here every six weeks or so,” she says.

Still, planning the interior on her own proved daunting for Campbell. “We had a pretty grueling schedule and also made time to travel here every six weeks or so,” she says.

“Yes, and she was working 60-plus hours a week, so trying to do it all on her own wasn’t going to work,” Johnson adds. “Margaret had a good sense of the history and the landscape surrounding this home; we just needed someone who could honor it.”

They asked a neighbor, who recommended Tammie Zech Interiors & Design.

“Tammie helped us tremendously,” Campbell says. “Everywhere, there are touches that are evocative of a schoolhouse, whether the subway tile or the flooring or even the light fixtures.” Those touches are tasteful, reverent even, while remaining true to the character of a classic Northwest home.

“Tammie helped us tremendously,” Campbell says. “Everywhere, there are touches that are evocative of a schoolhouse, whether the subway tile or the flooring or even the light fixtures.” Those touches are tasteful, reverent even, while remaining true to the character of a classic Northwest home.

“Her work helped make the resulting structure very unique and organic to the site, and very creative,” Johnson says. “It looks like it’s always been here.”

“People ask us, ‘Is it a new home or a remodel?’ ” Margaret says, proud of how their home so easily nestles into the landscape around them.

As the saying goes, a house is made of brick and stone but a home is made of love alone. Since moving in late last summer, Campbell and Johnson immediately welcomed a steady stream of guests. The couple christened it Cove House at Huck Farm.

Thanks to Margaret Campbell and Edward Johnson, this home, with its legacy of life and love of family, old and new, is gearing up for a brilliant second century.