(Photo courtesy Andre ten Dam)

Simply defined, a garden is a collaboration between nature and people. Plants cannot be willed to do what you want. They must be treated as partners and given what they need for water, light, soil, climate and so on. In return, gardens will give you what you need: food, flowers, beauty and peace. This the relationship between a plot of nature and its caretaker.

Few garden styles epitomize this relationship as strongly as that of the traditional Japanese garden. The hand of the caretaker is evident with every element having a purpose while maintaining a deep respect for nature. Kitsap County has such a Japanese-style garden within the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island.

Installed around 1955 by the founders, Prentice and Virginia Bloedel, with help from famous Japanese garden designer Fujitaro Kubota, the Japanese garden at the Bloedel Reserve has risen to become one of the top in the nation. The Japanese Garden Journal (www.rothteien.com) currently rates this garden as sixth best among Japanese gardens within the United States.

Like all gardens, it has had caretakers since its creation. One of those caretakers is a dedicated horticulturalist named Bob Braid, originally hired in 1985 at the Bloedel Reserve by John van den Meerendonk and Dan Hinkley, former managers at Bloedel turned local garden celebrities.

Like all gardens, it has had caretakers since its creation. One of those caretakers is a dedicated horticulturalist named Bob Braid, originally hired in 1985 at the Bloedel Reserve by John van den Meerendonk and Dan Hinkley, former managers at Bloedel turned local garden celebrities.

Braid’s duties at the time included general gardening but also work gearing up for the Bloedel Reserve’s official public opening in October 1988. This included various unusual projects like moving very large plants and revising the stone garden in front of the Guest House with guidance from Koichi Kawana from the University of California, Los Angeles.

After van den Meerendonk went into business for himself in 1990, Braid took over as horticultural superintendent. Five years later, the caretaker of the Bloedel Japanese garden left and Braid stepped into that position. With years of gardening experience and a love of conservatory horticulture, Braid was well suited to tending a traditional Japanese garden and has done so ever since.

(Photo courtesy Darren Strenge)

Prior to professional gardening, Braid served in the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War as a corpsman on medical transports that returned wounded service personnel to the United States. After leaving the military, he earned an associate’s degree in ornamental horticulture from Montgomery College in Maryland, no doubt influenced by his mother and by his grandfather, who was an avid fruit tree grafter. Braid’s continued academic pursuits took him out west to Washington state, where he received his bachelor’s degree in environmental geography from Huxley Environmental College at Western Washington University.

His first professional gardening job took him back to Montgomery, Maryland, as a gardener for Brookside Botanical Gardens. In one of those strange coincidences of life, Braid was asked to help push a car backward into a parking space at Brookside because reverse gear did not work. The man was interviewing for a job out west and did not want his prospective employer to see that his car did not work properly. That man was Richard Brown, and he was interviewing for a job as a garden curator with Prentice Bloedel at the future Bloedel Reserve. Unknowingly at the time, 10 years later Braid would work for Brown at Bloedel.

In 1977, Braid moved back to Washington state to work at the Seattle Center, where he met future Bloedel Reserve interim executive director, C. Dave Hughbanks, who was at the time the director of the Seattle Center. After two years there, Braid began work at the Volunteer Park Conservatory, where he learned Japanese garden pruning techniques from George Yamasaki, a skill that translated well when he joined the Bloedel Reserve in 1985.

The Bloedel Reserve was a good fit for Braid. He was able to live on site, a wonderful place to raise his son. Back in those days, Bloedel still stocked some of its larger ponds with trout and Braid and his son were able to fish when the grounds were closed. It was like having a 150-acre backyard.

In 1986, a high school student intern was hired. While this is a regular occurrence for the Reserve, this one was a bit of a matchmaker. The intern’s mother, Dorothy, was single. Braid was single. She introduced the two and they married in 1990.

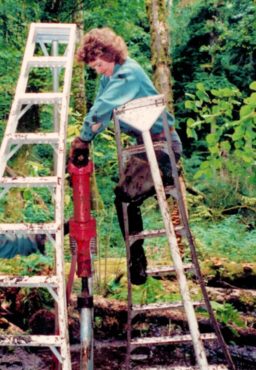

At the time, Dorothy worked for the Nickel newspaper but left to care for an ill family friend. She joined the Bloedel staff from 1992 to 1997 and worked on many things, but especially trails. The boardwalk through the bog was built with a lot of her muscle and sweat.

At the time, Dorothy worked for the Nickel newspaper but left to care for an ill family friend. She joined the Bloedel staff from 1992 to 1997 and worked on many things, but especially trails. The boardwalk through the bog was built with a lot of her muscle and sweat.

Ten years after Braid was first hired at the Bloedel Reserve, he assumed responsibility for the Japanese garden. His training in Japanese garden techniques and traditions and his interest in conservatory horticulture made him ideally suited to become the caretaker for this collaboration between people and nature.

Maintaining a Japanese garden involves much fine-detail work. There are trails to keep clear, trees to prune, moss to weed, a stone garden to keep free of leaves and footprints, and a host of other chores. Braid spends hours alone or with volunteers to weed and maintain the pristine appearance. Mossy areas, a common site in Japanese gardens, require particular care to not disturb the moss too much while rooting out interlopers.

Pruning is more involved in a Japanese garden than other gardens. The gardeners before Braid had not done much pruning and it took him about 10 years to bring the trees and shrubs back in line with traditional Japanese garden appearances.

Pruning is more involved in a Japanese garden than other gardens. The gardeners before Braid had not done much pruning and it took him about 10 years to bring the trees and shrubs back in line with traditional Japanese garden appearances.

Braid generally does fine pruning four times a year. He spends a lot of time on orchard ladders or in hip waders pruning trees that lean over the pond. Sometimes, he is on ladders placed in the pond. Each cut has to be considered for how it affects the final appearance.

Every tree is a little different with its pruning needs. Pine trees in particular are different than most. Cloud pruning of pines is common in Japanese gardens, with branches trained horizontally with “clouds” of foliage out on the ends. Because of how pines grow and respond to pruning, they are only pruned once a year, usually in May, when their shoots, called “candles,” are elongating. To produce tight growth for the cloud-pruned appearance, candles are pruned in two-year cycles. The first year, they are cut back by half. The second year, they are completely cut off.

The stone garden is a primary feature of the Japanese garden at the Bloedel Reserve. The fine-granite grit is smoothed flat and grooves are raked in around the perimeter and boulders. Braid spends a couple of hours a week removing leaves and footprints.

The stone garden is a primary feature of the Japanese garden at the Bloedel Reserve. The fine-granite grit is smoothed flat and grooves are raked in around the perimeter and boulders. Braid spends a couple of hours a week removing leaves and footprints.

The time and detail that Braid puts in as caretaker of the Japanese garden provides the community a beautiful, peaceful place to visit and contemplate. This is a duty that he does not take lightly, and it has been a part his garden ethic since the beginning of his horticultural career.

When working back east in the 1970s, Braid found himself assisting with the care of the bonsai trees that President Nixon had brought back from his famous trip to China. One of the trees was over 400 years old, prompting Braid to ponder the care. How many different caretakers had this tree seen? The people were gone but the tree was still here.

When working back east in the 1970s, Braid found himself assisting with the care of the bonsai trees that President Nixon had brought back from his famous trip to China. One of the trees was over 400 years old, prompting Braid to ponder the care. How many different caretakers had this tree seen? The people were gone but the tree was still here.

Like the bonsai tree caretakers, many gardeners are transient with respect to their gardens. The trees and land will persist beyond them, and they are really just taking care of the trees until the next caretaker comes along. Perhaps then the primary goal of a garden caretaker is to pass on a garden that is better than when it was acquired?

The Japanese garden at the Bloedel Reserve is certainly in good hands with Bob Braid. One of many gems in Kitsap County, Braid has devoted his career to this garden and the entire community benefits from his dedication and experience.