Close your eyes. Think of rowing, alone, across the Tacoma Narrows, maybe to Vashon, maybe to Commencement Bay. The currents are strong, wind fierce and, well, it is midwinter and sleeting.

Close your eyes. Think of rowing, alone, across the Tacoma Narrows, maybe to Vashon, maybe to Commencement Bay. The currents are strong, wind fierce and, well, it is midwinter and sleeting.

This was life before the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Yes, there were the Skansie Brothers’ ferries, but they just went from Tahlequah to Point Defiance. If residents of, say, Maury Island had other matters to take care of, it was up to them — and rowing was the way. Flat-bottom, working rowboats were a practical, if not a brutal mode of travel. Men’s and women’s bodies were strong, hands calloused.

Vaughn resident and artist Kurt Solmssen owns his family’s 1935 rowboat. Built in the Tide Flats and made of cedar and oak, the boat has withstood time and the family’s moves from Maury Island to Vaughn, even being lost in a deep fog, after which it was painted yellow — a cadmium yellow. During World War II, it had its own permit to row into the Port of Tacoma with strident rules: “1 occupant; no ammunition.”

Vaughn resident and artist Kurt Solmssen owns his family’s 1935 rowboat. Built in the Tide Flats and made of cedar and oak, the boat has withstood time and the family’s moves from Maury Island to Vaughn, even being lost in a deep fog, after which it was painted yellow — a cadmium yellow. During World War II, it had its own permit to row into the Port of Tacoma with strident rules: “1 occupant; no ammunition.”

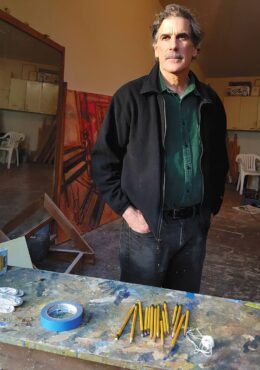

Solmssen and his wife, Rebecca “Becky” Schofield, moved to a family property in Vaughn in 1988. Solmssen grew up on the East Coast, but his mother’s family had deep Northwest and Tacoma roots. One grandfather, Everett York, was a lawyer for the railroad company when he came to Tacoma in the 1870s; the other, Clyde Backus, was Tacoma’s postmaster. His mother attended Annie Wright, then Wellesley College, and his father went to Harvard. Solmssen grew up in Bryn Mawr and visited the Vaughn home in the summers. The “boys” would bunk in a cinder block house, making root beer and crafting other boyhood memories.

Solmssen and Schofield met at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). PAFA had a reciprocal agreement with the University of Pennsylvania, so upon earning their diplomas at PAFA, the couple continued their studies at the University of Pennsylvania to earn their bachelor of fine arts degrees. When they graduated, they embraced a magical time in their young lives and moved to Spain’s Costa Blanca to paint.

Solmssen and Schofield met at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). PAFA had a reciprocal agreement with the University of Pennsylvania, so upon earning their diplomas at PAFA, the couple continued their studies at the University of Pennsylvania to earn their bachelor of fine arts degrees. When they graduated, they embraced a magical time in their young lives and moved to Spain’s Costa Blanca to paint.

From Spain, the pair moved back to Pennsylvania for a brief period of time, and while Solmssen was gainfully employed in sculpture conservation work, they began to think about a family and where to land. In 1988, Vaughn beckoned. Here, they built a sunlit studio, created a welcoming home, thrived artistically, raised their daughters and did what artists do — observe objects, landscapes and intimate settings to make them live and come to life for others. In their studio, their work lies side by side, each in a state of its own creation.

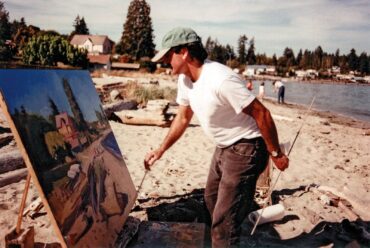

“I am basically a big plein air painter,” Solmssen said. That’s the term for creating art in the “real world,” on site, no matter the weather. And Solmssen is not kidding. His paintings are big, especially his diptychs. Some are perhaps 10 feet long.

“I am basically a big plein air painter,” Solmssen said. That’s the term for creating art in the “real world,” on site, no matter the weather. And Solmssen is not kidding. His paintings are big, especially his diptychs. Some are perhaps 10 feet long.

“I build my own tripods to hold the canvas, and just go and paint,” he said. These large outdoor oil paintings are Solmssen’s signature.

As for the yellow boat, it’s a major subject in his paintings. The boat is often front and center, while at times, it’s a background subject with family members in the foreground. It may be the only brightness on a snow-covered beach, or as if alive, looking on at a family bonfire. The yellow boat, painted in plein air, is indeed Solmssen’s muse. Its importance was even recognized by the Bainbridge Island Art Museum during the summer of 2021 in a major exhibition of Solmssen’s work titled “The Yellow Boat.”

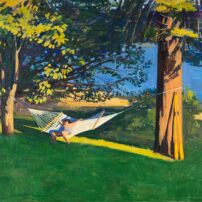

Schofield’s work, on the other hand, often focuses on glorious flowers. She is an avid gardener and not only paints on canvas, but with the planting of her garden, its flowers and their positioning. In August, dahlias and lilies, 4 or 5 feet high, abound — surrounded by grass, berries and old trees. It’s a country garden, welcoming summer in all her splendor.

Schofield’s work, on the other hand, often focuses on glorious flowers. She is an avid gardener and not only paints on canvas, but with the planting of her garden, its flowers and their positioning. In August, dahlias and lilies, 4 or 5 feet high, abound — surrounded by grass, berries and old trees. It’s a country garden, welcoming summer in all her splendor.

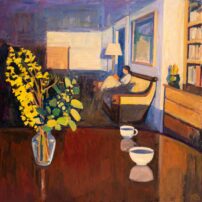

Every artist has influences: artists who preceded them and serve as a guide as to how to approach the work. One of Solmssen’s major influences is early 20th century, East Coast painter Fairfield Porter, for not only the way Porter manipulated his paint on canvas, but for what he painted — his family and those closest to him.

Every artist has influences: artists who preceded them and serve as a guide as to how to approach the work. One of Solmssen’s major influences is early 20th century, East Coast painter Fairfield Porter, for not only the way Porter manipulated his paint on canvas, but for what he painted — his family and those closest to him.

For those who visit the emergency room at St. Anthony Hospital in Gig Harbor, the first work of art they will experience, right at the entrance, is a classic Solmssen, flooded in yellows, blues, greens: an intimate picture of life on the Kitsap Peninsula. Solmssen said he paints his “domestic environment, in a painterly way.” For a nonartist, what in the world does this mean?

Solmssen explained: “Paint itself has a feeling. It is not just what the painting is about, but how it is painted. The process is trial and error, and the surface itself has an emotional impact. It is all about gathering information.”

The artist recognizes that life, especially the outdoor life of a plein air painter, is always changing. “It is as much about what you leave out in a painting as what you leave in,” he said. “It is all about how the images fit together.”

Painting is not always serious. “You should have fun with the paint and the physical aspect of being in the landscape,” Solmssen said. “It takes you out of yourself for hours at a time.”

His eyes sparkled as he looked over the landscape of his home, the yellow rowboat, the water. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be able to paint and forget the rest for a bit at a time?