Amy Burnett sees opportunities where others don’t and therein lies her creativity. She was busily clearing out her art gallery and Pyrex museum where she had created and connected with her beloved Bremerton when the pandemic lockdown came in March.

Amy Burnett sees opportunities where others don’t and therein lies her creativity. She was busily clearing out her art gallery and Pyrex museum where she had created and connected with her beloved Bremerton when the pandemic lockdown came in March.

Burnett went home to Belfair, taking some unfinished paintings of faces with her. They leaned against the walls in her studio, keeping her company, but the emptiness of her gallery with its 160 feet of display windows haunted her as she imagined the streets of Bremerton stripped of people.

An idea took hold in this creative woman. What if she filled the empty windows with paintings of faces? What if she populated downtown Bremerton and brought smiles to the faces of those few who passed the gallery on essential errands?

An idea took hold in this creative woman. What if she filled the empty windows with paintings of faces? What if she populated downtown Bremerton and brought smiles to the faces of those few who passed the gallery on essential errands?

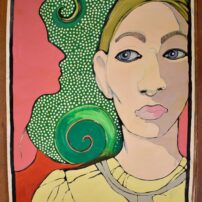

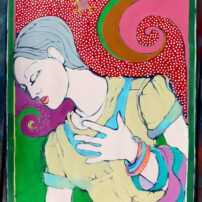

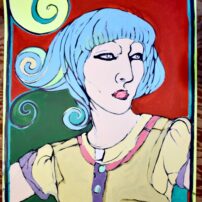

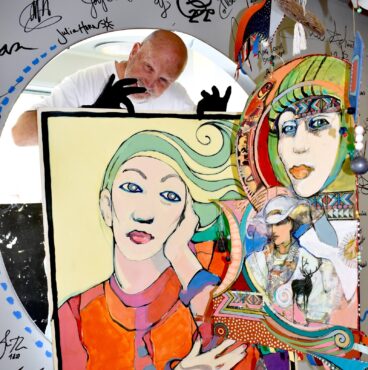

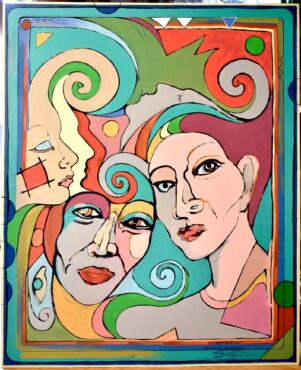

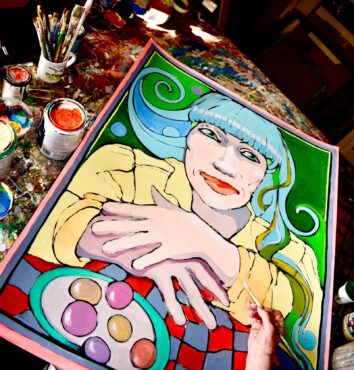

Burnett leapt into the opportunity of the question and painted like a whirlwind of colors. Before her painting storm — and lockdown — ended, she produced 40 sketches of bold faces on 32-by-40-inch boards. Each colorful painting took about three days to complete and she worked on several at a time. When asked if they were actual people or from her imagination, Burnett says they are all her, a visual record of her day-to-day experience in isolation.

In terms of art composition, isolation means stagnation to Burnett. Even isolated at home, she simply cannot accept stagnation. She’s dynamic and energetic, with a strong life force reaching out to connect and engage with others, whether she can see them or not. They live in her heart and imagination and inspire her art.

In terms of art composition, isolation means stagnation to Burnett. Even isolated at home, she simply cannot accept stagnation. She’s dynamic and energetic, with a strong life force reaching out to connect and engage with others, whether she can see them or not. They live in her heart and imagination and inspire her art.

In pushing to bring her inner world to light, Burnett gave her unseen fellow-locked-down people an unexpected gift. Viewers of this installation may be stimulated to see how people are engaging in the opportunity of this historic time. Are they stagnating? Or digging in to grow and delight their neighbors?

Burnett loaded her car with all 40 works of art and headed back to the gallery to do what she’s done for years. She used her art to create community. This time, Burnett made signs for people who passed by outside as she hung the show on the other side of the glass. The 40 fabulous faces filled all 160 feet of windows, the doorways and a wee window in the alley just as she had imagined.

Meanwhile, people on the street got into the act by placing signs on whatever piece called to them. Voilà, Burnett had drawn viewers into active participants in a piece of performance art. The show got hung, people had fun and created memories. With the addition of a few words, the painted faces became more evocative than they were alone.

Meanwhile, people on the street got into the act by placing signs on whatever piece called to them. Voilà, Burnett had drawn viewers into active participants in a piece of performance art. The show got hung, people had fun and created memories. With the addition of a few words, the painted faces became more evocative than they were alone.

About a month after she hung “Project Isolation,” Burnett created another community interaction as she reunited with a small group of friends. She painted large statements and placed them upside down on a table so no one could see what they said. Then, each participant picked one, carried it sight unseen to the windows and taped the statement above the painting.

When they had placed all the statements, they trooped outside to see what magic had occurred. The results were hilarious, thought-provoking and another form of performance art.

The works of “Project Isolation” express spontaneity with simple facial structures and uncomplicated backgrounds. A sense of strength comes from their straightforwardness — they demand attention. All 160 feet of them dare viewers to look and see the depth, confusion, pain and calm this isolation experience has called forth. Their eyes look right out at the spectators. At Bremerton. At the world. At this time.

The works of “Project Isolation” express spontaneity with simple facial structures and uncomplicated backgrounds. A sense of strength comes from their straightforwardness — they demand attention. All 160 feet of them dare viewers to look and see the depth, confusion, pain and calm this isolation experience has called forth. Their eyes look right out at the spectators. At Bremerton. At the world. At this time.

Burnett’s Process

Burnett says she begins painting with an idea or theme and paints in series. First, she paints from that mental concept until the idea becomes embodied in her. At that point, she goes for it with energy and fearlessness, following her philosophy that more is not enough.

She calls herself a “contemporary compositionalist” and is a master at pulling the eye in and directing it to flow throughout the painting until the viewer is moved, literally and emotionally. Burnett paints a series until it burns itself out in her. Near the end, full-blown gallery paintings emerge.

She calls herself a “contemporary compositionalist” and is a master at pulling the eye in and directing it to flow throughout the painting until the viewer is moved, literally and emotionally. Burnett paints a series until it burns itself out in her. Near the end, full-blown gallery paintings emerge.

Burnett never quits on a piece. She stops if she’s stuck but she comes back to it later. The object is to get in there and paint. If a piece is ruined, she says she must learn the lesson and get busy painting again. Don’t take yourself or your work so seriously that you quit, she admonishes — paint.

One of her life goals is to use up all of her art supplies: acrylics, graphite, brushes, house paints, papers and canvases. This artist will be painting for a good long time based with the size of her stash.

Her “Parade Pony” series pushed the idea of horizontal paintings. How narrow? How long? What were the limits? She worked with the idea of being up there on a pony where one can be seen — or not.

Her “Parade Pony” series pushed the idea of horizontal paintings. How narrow? How long? What were the limits? She worked with the idea of being up there on a pony where one can be seen — or not.

For years, Burnett painted her human subjects so the eyes were hidden. Men and women wore large hats with luscious shapes and deep shadows shading the eyes. The goal was not to limit the viewer’s experience to a specific person but to evoke a timeless, universal, dream-like quality. Who is it? What does it mean?

Previous series wandered into explorations of ferns and Native American motifs. One series focused on Northwest’s Chief Seattle. The Suquamish Tribal Museum owns one of those canvases. Southwest Native Americans appear with colorful ribbons and feathers on dancing horses with swirling ancestral spirals.

Salmon, a frequent motif, reminds her of her husband, Earl Sande, a third-generation Belfair resident. These varied symbols mix and mingle on her canvases traveling from one series to another, focused images merging with shadow images, outlines of swirls that turn into a salmon, a hand, a pony, a fern. Circles are movement and they mix with spiraling shapes that move the eye and sometimes create flat resting spaces. Sometimes Burnett’s circles are as simple as a dotted background.

Salmon, a frequent motif, reminds her of her husband, Earl Sande, a third-generation Belfair resident. These varied symbols mix and mingle on her canvases traveling from one series to another, focused images merging with shadow images, outlines of swirls that turn into a salmon, a hand, a pony, a fern. Circles are movement and they mix with spiraling shapes that move the eye and sometimes create flat resting spaces. Sometimes Burnett’s circles are as simple as a dotted background.

Born and raised in Bremerton, Burnett doesn’t give up on her town or the diversity of its people any more than she’d give up on a painting. She promoted her hometown continually in her columns that appeared in The Bremerton Patriot, Kitsap Peninsula Business Journal and, most recently, WestSound Magazine. Art-wise, one of many community projects she spearheaded is the Northwest forest mural on two sides of the Salvation Army building and the back of the 7-Eleven store. The artists, business patrons and city council came from all levels of the city’s society.

Her building at the corner of 4th and Pacific hosted many fundraising events for formal nonprofit organizations like the Salvation Army or local history museums, as well as for independent efforts helping artists, homeless teenagers and other spontaneous needs of the moment.

Her building at the corner of 4th and Pacific hosted many fundraising events for formal nonprofit organizations like the Salvation Army or local history museums, as well as for independent efforts helping artists, homeless teenagers and other spontaneous needs of the moment.

Even as she’s shutting the door to her gallery of 28 years, Burnett is tossing around ideas on how to donate the final painting of “Project Isolation” series and ignite another fundraising event. Maybe she will throw one last community-art shebang in the gallery. Her eyes light up with possibilities.

The exhibit will hang through (at least) September. Viewed from the sidewalk, it is a safe activity and a valuable view of present time. As an extra bonus, look between the paintings into the empty gallery where murals painted by both artists and nonartists over the years populate the walls. These figures may be isolated and dancing in the dark, but they, too, are living history. Art, music, community, participation — it’s all just around the corner.