It starts with a piece of wood — often a very big piece. Big, as in a 10-foot-long log or a huge slab of Western red cedar, Douglas fir, big leaf maple, or perhaps even a large chunk of cherry, black walnut or beech.

It starts with a piece of wood — often a very big piece. Big, as in a 10-foot-long log or a huge slab of Western red cedar, Douglas fir, big leaf maple, or perhaps even a large chunk of cherry, black walnut or beech.

Then Poulsbo artist James Nybo fires up his chainsaw and starts carving. Eventually, he puts the chainsaw aside and picks up his chisels and other hand tools to create a shape and form from the wood. Then comes hours and hours of hand-sanding and often inlaying bits of abalone, glass, metal, stone or a found object.

The results are works of art — Buddhas, sun faces, goddesses. Or tables. Or altars.

It all began one day years ago when Nybo was cutting firewood.

“I picked up a piece of fir and I thought maybe I could make that ordinary piece of wood into a shape of some kind,” he said. “Next thing I know, I’m carving an intricate end table inlayed with Mother of Pearl.”

As soon as the sculpture bug had bitten him, he knew he needed a place to turn the wood bits into art. So he cleared a 4-foot space in an old storage space. “And it turned into an adventure,” he said with a smile.

As soon as the sculpture bug had bitten him, he knew he needed a place to turn the wood bits into art. So he cleared a 4-foot space in an old storage space. “And it turned into an adventure,” he said with a smile.

Not long thereafter, Nybo learned that a man who lived nearby had to move his huge log yard.

“He had a wood mill for milling boards and he had stacks of wood as big as houses,” Nybo recalled. “He told me I could have it all, but I had to move it myself.”

Nybo found a deal on an old dump truck, and it took more than a year to move all the wood. Much of it turned out to be rotten and unusable, but enough of it was workable to make it worth all the effort, because Nybo had decided that he wanted to use big wood.

“As a kid growing up in woods in Southeast Alaska, I spent a lot of time hanging out with loggers and eventually I learned how to use and rebuild a chainsaw,” he said.

That ended up being an important skill. Early on, Nybo decided that he didn’t want to do “the kind of art that other people were doing.”

When he starts working on a piece, he puts all of his tools around him in a circle, then switches from chainsaw to tiny chisel to some other hand tool.

When he starts working on a piece, he puts all of his tools around him in a circle, then switches from chainsaw to tiny chisel to some other hand tool.

He often uses tools in unusual ways. That comes, in part, from living in the Alaska woods, and, before that, living in Forks with no TV or electronic gadgets.

“Mostly I just read and drew,” he said. “I got trained to think outside the box to solve problems. If we wanted to get supplies, we had to make sure the boat would work. We had to make do with what we had and to make stuff ourselves.”

In Alaska, his mother’s “super-educated” boyfriend rebuilt the family’s fishing boat from old airplane parts.

In Alaska, his mother’s “super-educated” boyfriend rebuilt the family’s fishing boat from old airplane parts.

“He was really big on education. He’d quiz me on all kinds of stuff when we were out fishing, so I learned to really like learning new things,” Nybo said.

He remembers that one day, he sat down and looked really carefully at his hands and decided then and there that he “just had to do something with them.”

Nybo is also a musician. He played bass in a band on Bainbridge Island for many years and hung out with some well-known Northwest musicians. He also worked for a landscape architect for several years, learning to work with stone and brick and other skills that that have come in handy.

In his day job, Nybo teaches aikido and does integrated body work, all of which involves a lot of movement and a focus on the connection of body, mind and spirit.

In his day job, Nybo teaches aikido and does integrated body work, all of which involves a lot of movement and a focus on the connection of body, mind and spirit.

“So many of my ideas for sculpture pieces come from movement and energy,” he said. “It’s like it starts with a thought and that turns into movement — translating the entire thought, which is imagination, into movement, which is the actualization.”

It also means learning economy of motion and effort and concentration, and letting go when necessary.

“It’s working with the push of the past and the pull of the future, which is not always a smooth transition,” Nybo said. “I call it being on ‘the ragged edge of the now.'”

“It’s working with the push of the past and the pull of the future, which is not always a smooth transition,” Nybo said. “I call it being on ‘the ragged edge of the now.'”

He’s very aware of the “state of oneness” that exists in the creative process.

Nybo might look at a log for many months, observing the shape, size and the grain.

“Sometimes I ‘see’ something, but then I stand up on the log and I see a different perspective,” he said.

He often stands the log on its end and just observes it as he walks around.

“Once I start cutting into it, I discover that it’s not the thing that I visualized after all,” he said. “The wood can impose its will on me and me on it, and it’s all a matter of being open to whatever comes, not trying to control it.”

“Once I start cutting into it, I discover that it’s not the thing that I visualized after all,” he said. “The wood can impose its will on me and me on it, and it’s all a matter of being open to whatever comes, not trying to control it.”

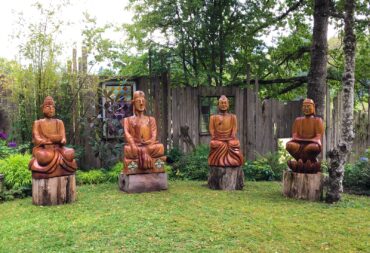

All the wood he uses is salvaged. The Buddhas, for example, are from old-growth cedar logs that have been cut decades ago and have been sitting and curing for a very long time.

“They’re like beautiful, ancient beings,” he said.

Everyone Is Creative

One of Nybo’s biggest pet peeves is when someone looks at his work and tells him he’s so lucky to be blessed with so much talent.

“I tell them, no — not blessed, just lucky to have the time and the skills to be able to do art,” he said.

“I tell them, no — not blessed, just lucky to have the time and the skills to be able to do art,” he said.

He believes that creativity lives in every individual.

“It’s not some special thing that I have. I work really, really hard with my art and I don’t think the ‘talent’ was somehow just given to me,” Nybo said.

He also feels strongly that encouraging children — indeed, everyone — to do art is important.

He also feels strongly that encouraging children — indeed, everyone — to do art is important.

“When someone says, ‘Oh, I could never do that,’ they should be told that it’s maybe true that they can’t do this, but they can do something else that’s creative,” he said.

Recently, Nybo has started working with stone, making stone puzzles with pieces that fit together, drawing on what he learned working for the landscape architect. He’d like to collaborate with other artists to make large installation artworks for public places.

“I’d really like to take this ‘puzzle’ concept further,” he said. “It’s very cool to have a big pile of logs that I could turn into big puzzle pieces to go in some public space. It would be fun to see the interface with people and the volume, mass and size of big art. I have a plethora of ideas and I’d love to collaborate with other artists to do big pieces.”

The best place to see Nybo’s work is Molly Ward Gardens on Big Valley Road in Poulsbo. He’s lived there for more than 20 years in a house just above the main garden areas, helping with landscaping, building projects and stone work, as well as using other skills he acquired when he worked for the landscape architect. Four of his big Buddha sculptures keep watch in a shaded open space in the gardens. Other pieces are set along the paths, nestled among the trees and perennial plants.

Learn more about James Nybo at omwood.org.