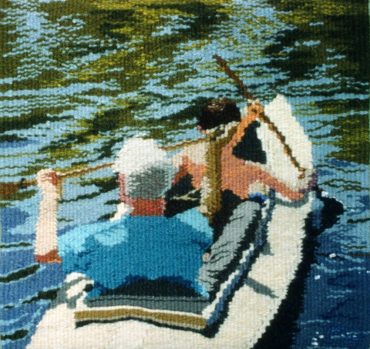

When you see Cecilia Blomberg’s work from a distance, you think it’s a painting. Look closer and you see that the “paints” she uses are actually yarn.

Blomberg is a tapestry weaver, known the world over for her creativity and skill.

Her tapestries adorn walls in the U.S. Air Force Academy, numerous public buildings in the Pacific Northwest, private homes and even a centuries-old castle in Scotland.

Blomberg was born in Sweden into a family that was filled with a creative spirit. When she was very young, the family moved from a tiny apartment to a 13-room house outside of Sundsvall.

“The house was filled with the previous owners’ furniture and had a fireplace and wonderfully painted ceilings,” she recalled.

It was a child’s paradise next to woods, with fruit trees in the yard and lots of outdoor spaces to explore.

Several of the upstairs rooms of the house were occupied by her father’s business. He was an artist and graphic designer and often rinsed his used silkscreens in the family’s bathtub.

“The tub was always very colorful,” Blomberg said with a laugh.

She always had art materials to play with.

“I loved to draw and paint and I used to draw floorplans in the snow in the winter because I wanted to be an interior architect,” she said.

When she learned that she would need to spend two years in an architect’s office before she could enter architecture school, Bloomberg’s thoughts turned to other artistic paths. In 1971, she was accepted into the National College of Art, Craft and Design, where she earned her master of fine arts degree.

Her college experience was especially rich and rewarding. Outside of school, she worked at a public workshop run by the city of Stockholm that included instruction in pottery, weaving and even very practical skills such as how to make one’s own clogs and mend clothes.

“It was a great experience,” Bloomberg said. “We worked a lot with street kids and low-income people. There might be an old man, bent over with age, learning how to remake his clothes to fit his bent posture, sitting next to a young punk rocker. Everybody was getting to know each other.”

She studied painting, drawing, sculpture and other art forms, but when she tried weaving on a frame loom, she “just totally got lost in it,” she said.

Down the street from the college, a young American man had a leather workshop where he and a couple of friends made bags, belts and other leather items. She and the young man, named David Lerman, were mutual friends with a couple of American girls, who introduced them to each other in 1974. In 1976, Bloomberg and Lerman were married.

“David wanted to return to the U.S. to finish his PhD in sociology at the University of Oregon, so in 1977, we moved to Eugene, Oregon,” Bloomberg said.

There, her talents were quickly recognized and in 1979, she was commissioned to weave several pieces for a local church. A few years later, the family move to Portland and more commissions followed, including commissions from a medical center in Klamath Falls and the Bonneville Power Administration.

There, her talents were quickly recognized and in 1979, she was commissioned to weave several pieces for a local church. A few years later, the family move to Portland and more commissions followed, including commissions from a medical center in Klamath Falls and the Bonneville Power Administration.

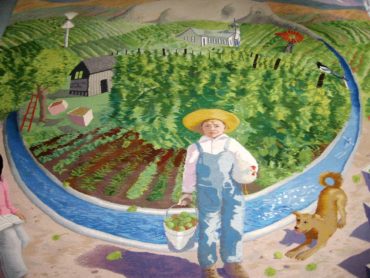

When Lerman accepted a job with Tacoma Power’s energy conservation division in 1989, the couple moved to Gig Harbor and soon, Bloomberg was accepted onto the Washington State Arts Commission artist roster. She has since been commissioned for many state-funded art projects, including tapestries for the Washington State University Vancouver library, Grays Harbor College in Aberdeen, Moxee Elementary School, McMicken Heights Elementary School in Seatac and Sacajawea Elementary School in Richland. Most of those pieces are large; several are more than 20 feet wide.

About the time Lerman retired in 2005, Bloomberg was invited to take part in a tapestry re-creation project at Stirling Castle in Stirling, Scotland.

About the time Lerman retired in 2005, Bloomberg was invited to take part in a tapestry re-creation project at Stirling Castle in Stirling, Scotland.

The castle was built in the 1500s and in 2001, several foundations and other organizations collaborated to have it restored to its original splendor. It’s estimated that when James V built it for himself and his new bride in 1514, the castle contained more than 100 tapestries, including a set of six pieces depicting the history of the unicorn.

As part of the castle’s restoration, West Dean Studio in the south of England was commissioned to create a set of seven tapestries based on the well-known “The Hunt of the Unicorn” to hang in the castle after its restoration. A satellite studio was set up inside Stirling Castle, where Bloomberg and another weaver worked. In all, a team of 20 weavers from all over the world worked on the project. The original tapestries, which hang in the Cloisters in New York City, tell the story of the unicorn being hunted down, killed and finally reborn.

The couple lived in Stirling for two years — 2005-2007 — while she wove her part of the tapestry. The project was eventually finished in 2013 and is hung in the queen’s quarters at the castle. Queen Elizabeth attended the ceremony when the new tapestries were dedicated.

The couple lived in Stirling for two years — 2005-2007 — while she wove her part of the tapestry. The project was eventually finished in 2013 and is hung in the queen’s quarters at the castle. Queen Elizabeth attended the ceremony when the new tapestries were dedicated.

When she returned from Scotland, Bloomberg said, she patted her loom in her home studio and declared, “Now I need a good commission.”

Several state arts commission projects followed and then came a series of eight tapestries of saints for the Air Force Academy Catholic Chapel in Colorado Springs. Those were completed in 2017.

When she receives a commission, the first step is to visit the site and meet with the commissioning committee in person.

“We look at the places where they think a tapestry should go and we talk about any ideas they have for the piece,” Bloomberg said.

Then she begins her research about the subject or the location’s history and culture.

“I go to local museums and libraries and other sites in the area to get a feel for the place,” she said.

Sketching — lots and lots of sketching and “playing with ideas” — comes next. Finally, sometimes suddenly, the concept comes together and she presents a painted sketch and color samples to the client.

“The research can be almost as much fun as the actual weaving,” Bloomberg said. “And I love the process of sketching and including all the various parts of the concept.”

Sometimes symbolic images are hidden in the landscape — a native basket, a handprint from a cave painting, a beaver skin hat. The little “secrets” make it all the more fun for the viewer to look more closely and “discover” the hidden surprises.

“In a school project, I try to include lots of different things that relate to the specific area so the kids can learn about their surroundings and their history,” she said.

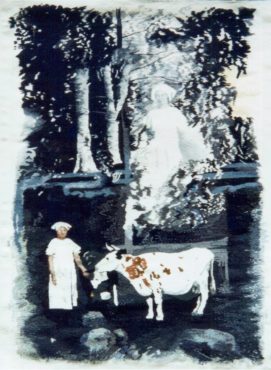

In the Sacajawea tapestry, for instance, there’s a ginko leaf hidden in the landscape and the “ghost” of Sacajawea is faintly — almost transparently — visible in a corner.

“But the little dog sees her,” Blomberg said.

The “Saints” project for the Air Force Academy was a years-long commission that evolved slowly. It began with an email asking if she would like to weave 60 tapestries of saints, each about 2-by-20-feet.

“I had to laugh about that,” she said. “I told them, ‘No, I’m not going to live that long. You should do it mechanically.'”

Finally, the academy narrowed it down to eight saints: Michael the Archangel, Joan of Arc, Ignatius of Loyola, Francis of Assisi, Joseph the Worker, Joseph of Cupertino, Thomas Aquinas and Cecilia.

“Choosing the saints was a project in itself for them,” she said. “They have 10,000 saints and had to choose just eight.”

Each saint’s tapestry is approximately 18 inches wide by 9.5 feet tall and each required months of research and sketching. And the client made numerous revisions until they all finally agreed on each design and the expression on each saint’s face.

“I think they learned as much about their saints as I did,” Bloomberg said.

“I think they learned as much about their saints as I did,” Bloomberg said.

The technique of weaving is basically unchanged from its beginnings in ancient Egypt and Sumaria. The loom is “warped” with many, many structural threads that create the foundation for the piece. The colored “weft” threads are woven over and under the warp.

“Everything has to be supported by the stuff below it,” she said.

A full-size “cartoon” (sketch) of the scene is drawn and affixed to the loom as a pattern for the weaver to follow. Then, inch-by-inch, the colored weft threads are added and the “picture” slowly comes to life.

Tapestry weavers have an intimate relationship with time, holding and nurturing a single vision for months — hundreds of hours — as the image slowly appears on the loom.

Tapestry weavers have an intimate relationship with time, holding and nurturing a single vision for months — hundreds of hours — as the image slowly appears on the loom.

For Blomberg, it’s a meticulous, meditative process.

“I can just get lost in the weaving and time seems to stand still. David will come into the studio and say, ‘Do you think we might eat today sometime?’ and I’ll suddenly realize that I’ve been at it for hours,” she said.

When the piece is finished, there’s often a big ceremony to cut it down from the loom.

“It’s a big, happy celebration to be finally finished,” she said with a laugh.

Currently, she’s working on a new spec piece inspired by a photo she took in Victoria, B.C., of steps leading down to the sea. Bloomberg is also creating a series of small, water-themed pieces for a show of work by fellow TAPS (Tapestry Artists of Puget Sound) members next fall at Tacoma Community College.