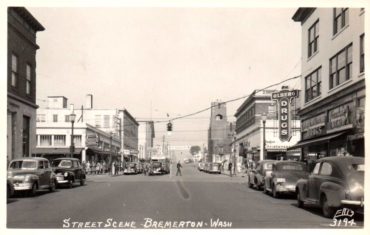

After dealing with the how and why of buying a building in a vacant, dank-smelling city, I moved in and art in Bremerton sprang like a million destined rockets to the moon. On May 1, 1991, the Amy Burnett Gallery and several other art-related businesses opened their doors in the 14,000-square-foot building at the corner of 4th Street and Pacific Avenue.

After dealing with the how and why of buying a building in a vacant, dank-smelling city, I moved in and art in Bremerton sprang like a million destined rockets to the moon. On May 1, 1991, the Amy Burnett Gallery and several other art-related businesses opened their doors in the 14,000-square-foot building at the corner of 4th Street and Pacific Avenue.

There was community thirst for possibilities, and we were ready to accommodate and up for an adventure. The wildest ride began and would last for over a quarter of a century.

The first decade was crazy strange — the world was crazy strange. In those early ’90s, Bill Gates was proclaiming that someday, every household would have a computer, at the snickering dismay of many.

And speaking of Bill Gates, he signed a T-shirt for one of our first fundraisers in the lower level of the gallery building. Also contributing signed T-shirts were LeRoy Neiman, Ken Griffey Jr. and Donna Howell-Sickles, to name a few. Thousands of dollars was raised for the YWCA. Fundraising opportunities continued for the next 25, and I would guess some million dollars was raised in total for community services.

In those early ’90s, we were like an island of hope and prosperity, a springboard of sorts, in a cold, gray city that was still empty and each day getting emptier. I remember standing on the sidewalk at the corner of 4th and Pacific, in front of my gallery where Christensen’s Shoes used to be. Of course, the town was empty, no one in sight, not even a mouse. The smell of wet sheet rock and concrete permeated the air and there was eerie stillness.

A couple came up and we talked. I can still see them — casually dressed and maybe in their 30s. They had just started a business in Seattle, something about online books, and on this day took the ferry to explore Bremerton. I never got their names, but my recollection was that the business was called Amazon.

I asked noted historian Fredi Perry about this, and she said my timing was off. Jeff Bezos at that time was in his late 20s and didn’t marry until 1993, so that put a damper on my memory share. Possibility still hangs in there, in my vague memory bank.

That brings to mind a day in the gallery a few years later when my art intern excused himself to take a call. It was from his financial adviser telling him to buy, buy, buy — Apple was revamping and selling shares for $17.

Loved the beginning of that tech boom; folks bought art like mad. I even joked about being able to perfectly load art in a Mercedes trunk blindfolded. That decade was like a perfect storm. I went into this being a recognized, award-winning artist, already advertising nationally, so with the Microsoft folks’ thirst for spending, there I was, “minutes from Seattle by ferry.”

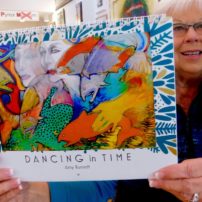

During the early ’90s I was also represented in fine art galleries throughout the country and in the United States Embassy Program (Bangladesh and Columbia). It was at this time that the C.M. Russell Museum selected me and three other artists to represent the nation’s Western contemporary artists in a featured museum exhibit.

During the early ’90s I was also represented in fine art galleries throughout the country and in the United States Embassy Program (Bangladesh and Columbia). It was at this time that the C.M. Russell Museum selected me and three other artists to represent the nation’s Western contemporary artists in a featured museum exhibit.

One day, a couple from the East Coast popped in the gallery saying, “Since we were in Montana, we thought we’d drive to Washington to visit your gallery.” In other words, I had a good business base. In those first few years, we were one of the top-earning art galleries in the country and almost 50 percept of sales were being shipped out. We had the space to establish an actual shipping department.

One year, the National Small Business Association selected six businesses as “small businesses of the year” and the Amy Burnett Gallery was the only West Coast business selected. This was also around the time that Money Magazine nominated Bremerton as “most livable city,” which I am still suspicious about today, in that Bremerton had an empty downtown and 50 percent of its housing was low-income rentals.

But art was good, for us, anyway. Collective Visions Gallery (CVG) moved to the Soriano corner building across from me, and Bill Gates and Paul Allen contributed a significant amount of money to help restore the Admiral Theatre performance arts facility. And the USS Missouri hadn’t left. It was a strange, time indeed.

But art was good, for us, anyway. Collective Visions Gallery (CVG) moved to the Soriano corner building across from me, and Bill Gates and Paul Allen contributed a significant amount of money to help restore the Admiral Theatre performance arts facility. And the USS Missouri hadn’t left. It was a strange, time indeed.

So many stories about the art gallery in Bremerton, it is hard to decide what to share about that beginning decade.

Censorship is a good topic with an interesting story. The building has 5,000 square feet on a lower level zoned retail and studio. It accommodated a professional touring dance company, Whitman & Dancers, and a couple of galleries/studios that had weekly nude-figure drawing sessions. No censorship.

Our gala art receptions were huge back then, never less than a thousand guests — food, music, the works.

In 26, years, I only censored once. An artist setting up her show in the lower Contemporary Gallery said, “There’s one controversial piece. I can paint shorts on him if you want.”

I said, “No worry, we work with nudes all the time.” Then I saw her exhibit. Oh my, the huge painting of the giant penis was the only painting on the far wall. I told her she had to have a sign at the top of the stairs reading “explicit body parts” to warn attendees. I couldn’t sleep all night, but had to censor the painting, because this show was following Phyllis Oliver’s children’s show.

I said, “No worry, we work with nudes all the time.” Then I saw her exhibit. Oh my, the huge painting of the giant penis was the only painting on the far wall. I told her she had to have a sign at the top of the stairs reading “explicit body parts” to warn attendees. I couldn’t sleep all night, but had to censor the painting, because this show was following Phyllis Oliver’s children’s show.

She took the painting down, and we hung it in the storage room behind the table where wine would be served. Word got out during the party, and it became an unintentional performance piece, as person after person would walk over and draw back the black velvet curtain to see the painting.

A million stories about bringing art to an old city, some sweet and some that would break your heart. It was apparent in my mind that in the very early ’90s, the city-powers-that-be wanted those empty buildings to be filled with offices. The mindset in this forsaken town did not seem to include art until an artist put her foot in the doorway and said, “Let me in.”