Tanzanites blue as deep water. Opals encasing ethereal galaxies. Pearls with the sheen of a satin negligee, and diamonds that twinkle like the look in a lover’s eye. Yes, indeed. There’s something about jewels that lights up a happy place in the human brain.

Tanzanites blue as deep water. Opals encasing ethereal galaxies. Pearls with the sheen of a satin negligee, and diamonds that twinkle like the look in a lover’s eye. Yes, indeed. There’s something about jewels that lights up a happy place in the human brain.

Born out of the furnaces of the Earth, crushed and blasted and buried for eons or rolled on the tip of an oyster’s tongue, natural gemstones, cut and polished, are captivating enough all on their own. But set them in a bold bezel or a fine filigree, and they become lifetime companions and repositories of the past.

No one understands this better than jeweler Leo Fried, owner of Blue Heron Jewelry on Poulsbo’s Front Street, and his associate, Nanz Aaland. Fried, Aaland and a team of jewelry designers and knowledgeable showroom “fashionistas” make Blue Heron a go-to destination for those seeking fine jewelry that’s not only beautiful and unusual, but often unique.

This is because, in addition to crafting a lot of the merchandise on the floor and providing repairs, restorations and appraisals, Fried’s shop specializes in custom design for clients who want something that’s one-of-a-kind.

“This is the place to get a piece you can’t get anyplace else,” says Fried, who started the business 30 years ago. “We spend the time it takes to find out what our customers like. Then we create a design that’s everything they want.”

Some custom-designed items are based on vintage family pieces; others have special meanings or remembrances. For example, one recent ring was commissioned by parents to commemorate their daughter’s love of film with the look of an old-fashioned movie reel crafted subtly into the setting. Another sinuous setting is based on a rocky riverbed.

“Jewelry is about celebrating family milestones and highly emotional events,” says Aaland, who is also the author of “A Jeweler’s Guide to Apprenticeships” and associate editor of Art Jewelry magazine.

She describes shopping at Blue Heron as experiential.

“We want to make it an occasion. We celebrate a young couple’s purchase of an engagement ring with champagne and chocolates,” Aaland says.

Fried and Aaland begin the design process by asking a client dozens of questions. It’s often most revealing, Fried says, to find out what someone doesn’t like.

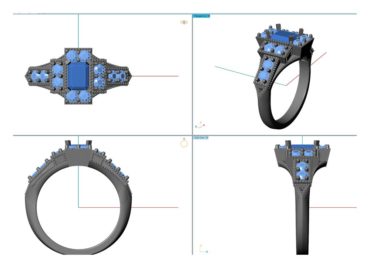

The next step employs computer-aided drafting (CAD) software, which has 25,000 design variations. A few days later, Blue Heron presents to the customer a prototype of the piece fashioned by a 3D printer. Once the design is approved and the materials are selected, Fried casts the metal and sets the stones — and an heirloom is born.

Working with customers also gives the designers ideas for their exclusive Blue Heron lines. A third of the jewelry shown on the floor is designed and fabricated in-house. Fried and Aaland are constantly exploring new directions and new techniques.

“The custom jobs often give us ideas that may have nothing to do with the order,” Aaland says. “Sometimes we create a new piece and a year later, we’ll see something similar in a trade magazine. We’re kind of cutting edge.”

Fried agrees. “I may have to find a new technique to make a design I’m imagining,” he says.

In 2017, Blue Heron Jewelry took first place in responsible practices in a Manufacturing Jewelers and Suppliers of America (MJSA) design competition for a custom-designed ring. The recognition was inspired by the company’s dedication to ethically obtained and sustainably made jewels and jewelry.

One facet of the award is Blue Heron’s sourcing of gold from suppliers who recycle. Fried explains that enough gold has been produced in the course of human history that, with recycling, no other gold need ever be mined. Gold, he says, is historically the most recycled material.

The award-winning ring showcases a stunning 3.47-carat tanzanite. Rich blue with violet undertones, tanzanite is one of the fair-trade gems that Fried and Aaland insist upon. Found only within an area of 5 square miles at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, naturally occurring tanzanite is a thousand times rarer than diamonds. At the current rate of mining, the lovely stone will be mined out in 25 years.

In fact, says Fried, the world is running low on raw, natural gems. After all, there are only so many, and humans are relentless at ferreting them out.

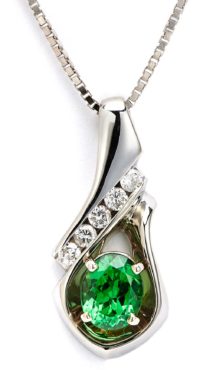

in 18k yellow gold

in 18k yellow gold (CAD/CAM Renderings)

Fried and Aaland are no fans of lab-created gemstones. For one thing, lab-grown stones may not exhibit the same wavelength as a natural gem or have the same chemical composition. For another, they say, because of the limited supply, natural is collectible. Manmade stones simply lack the mystique that makes an Earth-made gem so desirable.

“They’re something to set when there’s no natural stones left,” Fried says.

At Blue Heron, it’s not so much disdain for lab-created gems as admiration of the real thing.

“We love stones,” Fried affirms. “Stones are like candy.”

“They make your mouth water,” Aaland agrees. “The color, the depth, how well they’re cut — each stone is an individual.”

Gemstones come in every color of the rainbow. Sapphire alone covers the spectrum (if you include its sister corundum, ruby). Padparadscha sapphire, one of the rarest gems on the planet, is not only difficult to pronounce, but comes in an exquisite shade of orange-pink.

“A lot of gemstones aren’t generally known to the public,” Fried points out.

“Like Ethiopian opal,” Aaland adds. “It looks like jelly.”

Pale-pink morganite, related to emerald and aquamarine, has also been gaining attention. Tsavarite garnet can equal the hue of the finest emerald; it ranges from bright yellow-green to deep green and blue-green, and it has a high-refractive index, which gives it a high level of brilliance. Zircon — available most commonly in shades of sky blue, golden brown and a colorless form that rivals diamond — is doubly refractive, meaning it has uncommon brilliance and fire.

Of course, it’s hard to argue with the classics. Diamonds are also miracles of refraction, as well as the hardest element known to man. Each diamond is one billion years in the making. In addition to using diamonds as a center stone, Fried recommends setting diamonds around a colored, center stone to make its color even more intense.

Although diamond is now the engagement ring standard, this wasn’t always so. Fried notes that a pearl — a perfect, lustrous pearl — was once the gem of promise.

“Until the 1920s, a natural pearl was customary for an engagement ring,” Fried explains. “Cultured pearls killed that tradition. Nothing, in my opinion, looks better than pearls. They are the most feminine, natural element. They come polished and brilliant. Fine-quality natural pearls are very rare.”

At Blue Heron, jewelry is as individual as the person who wears it.

“We believe in pieces with intention,” Fried says. “Jewelry is an expression of personality. Our clients aren’t looking to match an outfit. We design pieces that stand on their own.”