Joan Tenenbaum has her feet firmly planted in two distinctly different worlds — the world of art and the world of science.

In her heart, she’s an artist, poet and writer and has been since she was a child. In fact, the very first artwork she created in high school won an award.

But at her parents’ urging, she put away her art tools and went to college to study anthropology, earning a doctorate degree in anthropology and linguistics from Columbia University.

In 1973, research for her dissertation took her to a tiny village in Alaska, where she lived with Dena’ina Athabaskans and wrote a grammar and dictionary of their endangered language. She also compiled 24 of their stories into a book, “Dena’ina Sukdu’a: Traditional Stories of the Tanaina Athabaskans.”

Tenenbaum also lived in other villages with Yup’ik and Iñupiaq Eskimos, teaching and coordinating programs for the University of Alaska. She still visits the villages to reconnect with longtime friends.

She’s often been told by fellow linguistic anthropologists that her work on the dictionaries is “the best introduction to the Athabaskan language available.”

“I thought my dissertation was probably just sitting on a shelf somewhere but people are actually using it for teaching and for reference,” she said.

During all those years of being immersed in academia, Tenenbaum continued to make jewelry. And she never gave up her dream of someday being a full-time artist.

That dream is what led her to Washington in 1990. She now lives in Gig Harbor and makes “anthropological jewelry” full time. She also lectures and teaches classes in jewelry design and creation.

“The anthropologist’s job is to live with the people, understand their culture and interpret it to the world. Usually this is done through books, which I’ve certainly done, but now I’m doing it through jewelry,” she said.

Tenenbaum’s jewelry reflects her life in Alaska — the landscapes, the natural environment and the culture and mythology of the Native people.

“I love making very detailed, wearable pieces that are nature- and culture-inspired,” she said.

She incorporates images of animals, masks, human figures, ancient artifacts or symbols of the cultures in which she lived and her pieces tell old, old stories that have been handed down through many generations.

Often the pieces convey environmental messages — reminders of the human connection to the Earth and nature — and many pieces evolve into series exploring a specific theme.

Her work often speaks of the three things that are the most important to the Native people — their families, the land and obtaining of food.

“A lot of my work includes symbols of the spirituality in the cultures in which I lived or are translations of ancient stories or artifacts,” she said. “It’s my way of paying homage to some of the last remaining hunting societies that have been kept alive by their deep connection with the Arctic land and animals that support them.”

Tenenbaum fuses her technical, intellectual and creative abilities into jewelry that is imbued with beauty, spirituality and mystery.

In 2012, the Anchorage Museum purchased two of her pieces: “Feasts of Tradition” and “Kela Nuch’iltan — We Found Little Brother: A Dena’ina Story.”

“‘Feasts of Tradition’ is a circular brooch/pendant that condenses the entire year of coastal Yup’ik Eskimo subsistence foods into one form, divided into three sections representing the areas where The People hunt and gather: tundra, ice and water,” Tenenbaum explained. “It incorporates many details of Yup’ik life.”

“We Found Little Brother,” a necklace, is Tenenbaum’s “very favorite cultural piece” that she’s ever made. It’s a traditional Tanaina Athabaskan story of a young boy who is adopted by a wolf and later becomes a sea wolf — a killer whale.

“The Dena’ina consider wolves to be their brothers,” Tenenbaum said.

She explained that when there was starvation or someone was lost in the woods and hungry, all they needed to do was ask their wolf brothers for help, and help would be given.

“It’s such an honor for me that the museum purchased these pieces,” Tenenbaum said. “Of course, it means that neither of these pieces will ever be worn as jewelry, but they’ll be on display for all to see there, in the museum.”

She uses a variety of techniques in her creative work — enameling, engraving, chasing, repoussé, forging, roller texturing, fold-forming, mokume gane, granulation, reticulation, damascene, keum boo, anticlastic raising and stone setting — to create the fascinating textures, colors and contrasts that narrate each piece. Many of her pieces also include precious metals and gemstones.

A few years ago, Tenenbaum began to explore the ancient, intricate and time-consuming technique known as cloisonné.

“I’d been interested in cloisonné for years but I didn’t want to try it because I thought there would be such a huge learning curve and that it would take me much too long to master — and that I’d have to take a year off from my regular artwork to get good at it, because it usually takes years to really learn it,” she said.

“It’s very intricate and very precise. But from the very first moment, there was no doubt in my mind that I would embrace it completely. I took to cloisonné like a duck takes to water,” Tenenbaum said with a smile.

One of the things that drew her to cloisonné is the ability to use color, and learning to work with colors was a transformative experience.

“It has just opened a whole new universe to my work,” she said.

There are more than 30 separate steps in every cloisonné piece and some steps must be repeated eight or 10 times.

“The word ‘cloisonné’ means ‘little cell’ or ‘compartment,'” Tenenbaum said. “You build these tiny little cells with gold wire using the tiniest little tweezers, and fill each cell with colored powder.”

Tenenbaum uses wire that’s 0.003 inches thick and 0.005 inches high. She rolls each piece of wire by hand to get it as thin as possible to get the detail she needs — “like creating a raven’s wing or a wolf’s head or a flower on a tiny scale.”

Then begins the multistep process of preparing the base, “drawing” with the wire, applying the colored powders and firing the piece again and again in a kiln.

The coloring starts with washing a small quantity of transparent enamel powder with distilled water. “The enamel will look cloudy if it’s not properly washed,” she said.

After hand-grinding the washed powder to an even finer consistency, she makes a domed base for the piece, then traces her pattern onto the base. She applies the wire to the tracing and fires the piece in a small kiln for a minute and 13 seconds at 1,500 degrees to adhere the wire but not melt it.

Using the tiniest sable paintbrushes, Tenenbaum picks up bits of colored enamel powder and applies each color into its wire cell to create gradients. Then the piece is fired again, another layer of color is applied and fired yet again.

“You repeat that whole process eight or 10 times until each wire cell is filled with color, and the color gets deeper and richer with each firing,” she said.

The wire work and enamel work on a single piece can take two or more days. And then, finally, the piece is put into its setting.

“I almost had a panic attack when I tried to do my first piece by myself, but now it feels so natural,” she said. “I’ve been using very meticulous processes in my work for 57 years, so this very precise, exacting technique was easy for me. And to be able to do things in color is just absolutely wonderful.”

Tenenbaum’s work is available at Stonington Gallery in Seattle’s Pioneer Square and is featured every year in a holiday show. This year’s show, which takes place in December, is themed “Landscape as Amulet” so Tenenbaum is creating pieces that will be “imbued with spiritual meaning,” she said, including a series of tiny spirit bear houses based on the Zuni bear fetish.

She also plans to make a large cloisonné piece — probably one that depicts the Northern Lights.

“They’re such vivid colors in Alaska,” she said. “And they actually make a sound that you just can’t describe.”

Next summer, Tenenbaum will teach a class about her special texturing techniques at Idyllwild Academy of the Arts near Palm Springs, California.

“I’ve always wanted to teach there and they only invite masters to teach, so I’m really thrilled to be invited,” she said.

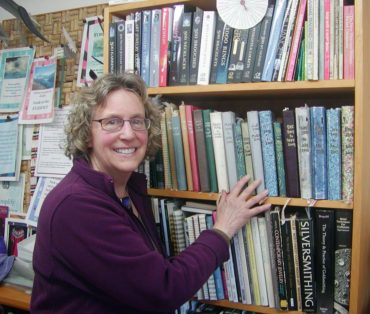

In addition to getting ready for shows, coming up with new ideas and working on commissions, Tenenbaum is also working on her archives, documenting her work as a linguist and as an artist.

“The archives are like a library and they aren’t of any use if you can’t find a specific thing. So everything has to be carefully catalogued and labeled,” she said. “My archives are my legacy. They’re my life story.”

The linguistic archive is finished and now she’s documenting her artistic career, collecting notes and sketches of every piece she’s created over the past 57-plus years, and also including her personal collection of her favorite work.

“I try to push myself to do something new every year,” she said. “That’s part of who I am — I feel like I simply must go into new territory.”