A long time ago, a quarter of a century has sped by as fast as humming birds in a summer flower field. The Amy Burnett Art Gallery has closed its retail operation in downtown Bremerton. From the beginning, a question was always asked, the most asked question in fact, “Why Bremerton?”

A long time ago, a quarter of a century has sped by as fast as humming birds in a summer flower field. The Amy Burnett Art Gallery has closed its retail operation in downtown Bremerton. From the beginning, a question was always asked, the most asked question in fact, “Why Bremerton?”

I was stunned in those early days, as a few folks walked in the gallery to say something like, “Why is a nice gallery in an awful town like this?” It wasn’t the outsider or tourist finding the town offensive. It was a local factor. I soon realized that there was a love-hate relationship with the old Navy city.

There was another equally asked question that first year, “How did you get the building?” To finally answer those questions, “why and how,” let me take you to the beginning. Some of the story may be a little dark. I have chosen not to disclose some names.

It was 1990. Bremerton had been thrown off a cliff and still hadn’t reached the bottom. J.C. Penney was packing its bags, Woolworths was juggling its existence and Radio Shack was still in operation. Most storefronts were empty. Nights were dark and dangerous, as groups of teens would gather and huddle in any lit building doorway, and prostitutes were conspicuously claiming ownership of street corners.

Enter me, a female artist assuming that with things this bad, there must be grand opportunities to find a screaming-good deal for a commercial building. Not so, I would soon find out.

Enter me, a female artist assuming that with things this bad, there must be grand opportunities to find a screaming-good deal for a commercial building. Not so, I would soon find out.

At this time, I was probably one of the top-earning artists being represented in fine art galleries throughout the United States and have been featured in most national art magazines. I was in Barbara Mack Gallery in Seattle, one of Amado Pena’s artists in Santa Fe and represented in Sedona by its oldest running gallery, El Mundo Magico. I was represented in Little Rock, Aspen and so on, and in the Embassy Art Program through the State Department.

Back to Bremerton, I had the means to buy a building and a reputation where I thought art buyers would come to Bremerton. Later I would advertise nationally, always saying, “minutes from Seattle by ferry and near terminal.”

I began by spending day after day walking up and down the city sidewalks, analyzing everything from how the sun reflected off windows at what part of the day to how long it took to walk from one point to another point, detail piled on detail.

There was a hole-in-the-wall art gallery on lower Pacific that was about to close, Brad Buskirk’s art gallery in Manette, Juan Rodriguez’s art studio on 1st Street where the South Pacific bar is now, and a gallery on the waterfront (then lumber yard area) where Anthony’s is now.

One day while on my investigative trek, I ran into that gallery owner. He walked with me as I shared my art gallery dream for Bremerton. He said that he thought “they” were trying to get rid of him and he was told, “We don’t want Bremerton to become an art commune.” Surprised, I remember stopping in my tracks, turning to him and saying, “Please repeat that, for I am going to repeat it to others,” and he did. Still not discouraged, I continued.

Why Bremerton? It was the hometown I returned to, where past generations had worked and raised families. The family business, B.H. Allen Plumbing and Heating, was located where now is Monica’s Social Club on 6th Street. And my other set of grandparents also lived on 6th Street, same location where Salvation Army is today.

Why Bremerton? It was the hometown I returned to, where past generations had worked and raised families. The family business, B.H. Allen Plumbing and Heating, was located where now is Monica’s Social Club on 6th Street. And my other set of grandparents also lived on 6th Street, same location where Salvation Army is today.

Finding a building to buy was not a piece of cake. In 1990, lower Pacific Avenue still saw some little shops, many with out-of-town owners — some hanging on for investment, some co-owned. I recall talking to someone in Seattle who said that it was in the will that the family couldn’t sell the small, two-story building on a cobblestone street where family had a business and lived upstairs.

The Soriano and Bremer families owned most of the downtown properties. The Sorianos weren’t about to sell anything, and the Bremer properties were being turned over in trust to Olympic College. I contacted the college/trust, wanting to possibly buy one of the many empty buildings, and the answer was no. Could I see inside the buildings? Answer, again, no, but I was told to call back in November.

The Soriano and Bremer families owned most of the downtown properties. The Sorianos weren’t about to sell anything, and the Bremer properties were being turned over in trust to Olympic College. I contacted the college/trust, wanting to possibly buy one of the many empty buildings, and the answer was no. Could I see inside the buildings? Answer, again, no, but I was told to call back in November.

To see this picture even more strangely, one needs to realize that as dead as Bremerton was, it had a symphony, an opera company, a performing arts company and theater (East Bremerton) and dance company.

To see this picture even more strangely, one needs to realize that as dead as Bremerton was, it had a symphony, an opera company, a performing arts company and theater (East Bremerton) and dance company.

The business leaders who were being asked for arts donations decided to form an appropriating group to disperse donations. I was invited to the first meeting along with other arts groups.

Toward the end of the meeting, I raised my hand and said, “I have the money, and no one will sell me a building.” Silence. After the meeting, I was asked to stay and was taken to a side room. One of the men said, “You don’t understand business. Someone will be buying Bremerton, and maybe they will sell you a building.”

Wow, that’s deep. This wasn’t street gossip. Bremerton business leaders actually thought an entity would be buying the old city, but that thought was short lived.

November came and I called the Olympic College Trust, “It’s Amy again.” I remember exactly where I was standing in my art studio when I very specifically asked the head guy, “Will you be considering merit or is it just money?” and without hesitation, the answer was, “It’s money.”

November came and I called the Olympic College Trust, “It’s Amy again.” I remember exactly where I was standing in my art studio when I very specifically asked the head guy, “Will you be considering merit or is it just money?” and without hesitation, the answer was, “It’s money.”

As I stood on the sideline, the “for sale” signs went up in all the windows. No one was jumping in to buy a downtown building but I was still there. For the first time, I wrote a letter to the editor expressing my desires to bring art to Bremerton and asking for support.

The response brought tears, as a few town leaders stepped up to the plate to say, “Go girl, we got your back.”

The response brought tears, as a few town leaders stepped up to the plate to say, “Go girl, we got your back.”

Wanting other arts to join me, I filmed. In fact, I was the only one who filmed inside all those Bremer Trust buildings, most obsolete and a bit bizarre, especially the place on 5th behind the Admiral Theatre where a Bremer mistress lived on the second floor. I was told it was called the Caroline Building and there was an adjoining secret passage to enter the Bremer office in the theater.

A lot of work, a building selected, much negotiating and loan approved. The bank vice president walked me to my car. He said, “I don’t know who advised you on your loan, but you’d better thank him. I wanted to say, “It was me, you silly man,” but kept my mouth shut and smiled.

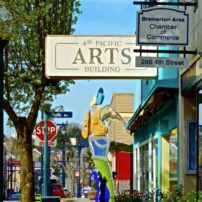

A work party ensued. The community came out in full force. The 1922, 14,000-square-foot building that once housed the Christianson Shoe Store and the Frances Shop began to transform. After an evening work party, I went outside and told a prostitute, “This is my corner now.”

A work party ensued. The community came out in full force. The 1922, 14,000-square-foot building that once housed the Christianson Shoe Store and the Frances Shop began to transform. After an evening work party, I went outside and told a prostitute, “This is my corner now.”

On May 1, 1991, the Amy Burnett Gallery opened and I also brought in other businesses: Sound Design, Art Concepts and Whitman and Dancers. The next year, Collective Visions Gallery opened down by the ferry and later moved across from me.

Those first couple of years in an empty, gray, old city where streets smelled like wet sheetrock, I advertised nationally — and they came. I represented well-known artists, won national business awards and sold tons of art. The first few years, 50 percent of art sales were shipped out of town. Unfortunately, now there was no time or energy to accommodate sending art to other galleries.

Because of all the wonderful community support, in turn one of our goals was to accommodate artists and community services. Besides an art scene, I am pleased that an old building in Bremerton was sold to an artist, and that building provided space that probably generated a million bucks toward charitable community services.