The hand-stenciled sign on Annette Fourbears’ small Indianola studio says, simply, “Baskets.” That’s definitely an understatement because this multifaceted artist also paints, sculpts and writes poetry.

The hand-stenciled sign on Annette Fourbears’ small Indianola studio says, simply, “Baskets.” That’s definitely an understatement because this multifaceted artist also paints, sculpts and writes poetry.

One of her most-visible public artworks is the 17-foot “Wheel Totem Pole” in Ventura, California, that the city commissioned for one of its parks.

Here in the Northwest, however, Fourbears is best known for her woven baskets, covered with beadwork, that tell stories of America’s Native people.

Fourbears was born in Kansas of Lenni Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, Cherokee and European heritage.

“I was born into a family of artists, writers and musicians,” she said as she wove a pine needle basket that was included in a duo-show of work by her and her husband, Joseph Fourbears, that opened in March at Poulsbo’s Front Street Gallery.

“I was born into a family of artists, writers and musicians,” she said as she wove a pine needle basket that was included in a duo-show of work by her and her husband, Joseph Fourbears, that opened in March at Poulsbo’s Front Street Gallery.

“What we did for fun as a family, when I was growing up, was to go out into the woods and sketch,” she said. From her father, a former priest, the children learned the names of all the birds, animals and trees. Her mother taught the children the Indian stories that had been handed down through generations.

It’s those stories — of her own Delaware people, Plains people and Northwest Tribes — that Annette Fourbears tells through her beaded baskets.

She started weaving about 20 years ago when she and Joseph lived in southern California. “I started with a group of California Native weavers and we used materials that grow in that area,” she said.

She started weaving about 20 years ago when she and Joseph lived in southern California. “I started with a group of California Native weavers and we used materials that grow in that area,” she said.

When the couple moved to the Northwest in 2004, Fourbears met Kathy Ervin, a Kansas Wyandot who lives in Sequim, and other Northwest Native weavers who introduced her to local materials. “Here we have things like cedar and sweet grass and sedge and pine needles,” she said.

Ervin taught Fourbears cedar bark weaving. The bark is harvested between June and September when the sap is up, she said.

“You make a cut near the base of the cedar tree and then walk backwards as you pull the bark from the tree,” she said. A good yank pulls the strip of bark loose.

“You make a cut near the base of the cedar tree and then walk backwards as you pull the bark from the tree,” she said. A good yank pulls the strip of bark loose.

The fresh bark is set aside to mellow for a year. Then, before cutting it into fine strips, it’s soaked in hot water several times to clean it.

Sweet grass is harvested in August. “You just pull the blades and don’t disturb the roots. You soak it in hot water for three hours before you start weaving and the basket must be finished that day or the grass starts to get funky,” she said.

Most of Fourbears’ baskets now are created from pine needles and sinew or waxed linen thread, using a coiling style she learned from Jacque Rickard, a Walker River Paiute who lives on the Lummi Reservation near Bellingham.

Most of Fourbears’ baskets now are created from pine needles and sinew or waxed linen thread, using a coiling style she learned from Jacque Rickard, a Walker River Paiute who lives on the Lummi Reservation near Bellingham.

Fourbears harvests the pine needles from her own trees, then “cooks” them in a warm oven in a solution of glycerin and water. Next, they’re rinsed and spread to dry for at least two weeks. The process makes the pine needles supple and easy to work with and protects them from insects and wear. “But they still smell wonderful, like pine trees,” she said.

“Jackie also taught me the Paiute style of covering the basket with peyote beadwork. She uses traditional Paiute designs that are very colorful, abstract and geometric. They’re very beautiful, but I love my Delaware heritage and I wanted to put my own cultural stamp on my baskets — and that’s how the story baskets were born,” Fourbears said with a smile.

“Jackie also taught me the Paiute style of covering the basket with peyote beadwork. She uses traditional Paiute designs that are very colorful, abstract and geometric. They’re very beautiful, but I love my Delaware heritage and I wanted to put my own cultural stamp on my baskets — and that’s how the story baskets were born,” Fourbears said with a smile.

Many of the stories come from her own Delaware culture; others come from Joseph’s Omaha, Ponca and Lakota traditions and still others have been given to her by other Northwest Native weavers.

Many of the stories come from her own Delaware culture; others come from Joseph’s Omaha, Ponca and Lakota traditions and still others have been given to her by other Northwest Native weavers.

“At first I was hesitant to share the stories because in our Delaware culture, stories are sacred and I felt that other tribal people probably felt the same way,” she said. “I wanted to make sure I wasn’t overstepping by putting the images of the stories on my baskets.”

The solution, she decided, was that if she dreamed about a story, she would know that it was all right to share it.

The dreams also inspire the images she uses in the beading design.

“I’m a lucid dreamer and the dreams are very clear, and I remember everything from the dream — the scenes, the colors, the patterns, everything,” she said.

Sometimes the dream comes within a month. Other times, it can take two years. “But I wait. The dream gives me permission. No dream, no basket,” Fourbears said.

Sometimes the dream comes within a month. Other times, it can take two years. “But I wait. The dream gives me permission. No dream, no basket,” Fourbears said.

She works out the dream-inspired designs on beading graph paper then creates the rest of the design freestyle as she works.

Whenever she’s making a basket — or any type of art — Fourbears is very attentive to her state of mind.

“I was taught that when you weave or do anything artistic, you can’t have negative feelings or thoughts. Art is a very soulful, creative process. It’s one way we’re like the Creator — we’re creating. So if I’m angry about something or have bad thoughts, I have to stop weaving,” she said. “Last year, it was hard to work because of all the negative stuff on TV and everywhere.”

Often when she’s making a basket, Fourbears meditates and adds little prayers in hopes that the person who buys the basket will love it as much as she loved creating it.

Often when she’s making a basket, Fourbears meditates and adds little prayers in hopes that the person who buys the basket will love it as much as she loved creating it.

“I’m very much in love with my Delaware culture and we have a belief that Kishelemukong, the Creator who created everything from thinking, is everywhere, emanating from everything,” she said. “He reads and knows all our thoughts and whatever he thinks is brought into being. So we’re taught to concentrate on what we want to have happen, what we want to be. We’re raised with this very ancient belief from the time we’re tiny children.”

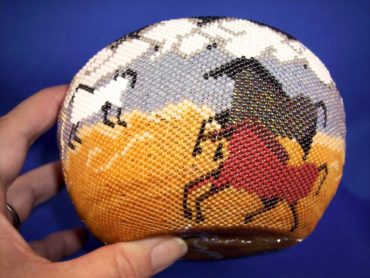

Many of the tribal stories she shares through her baskets — like the story of Rainbow Crow bringing fire from the sun — go back to a time before the ice age when the world was “warm and abundant.” There’s also a migration story — Walum Olum, the Red Record — that tells about the journey from the north to warmer places.

Many of the tribal stories she shares through her baskets — like the story of Rainbow Crow bringing fire from the sun — go back to a time before the ice age when the world was “warm and abundant.” There’s also a migration story — Walum Olum, the Red Record — that tells about the journey from the north to warmer places.

The basket called “Why the World Will Never End” tells a story from her own Delaware tradition about an old woman who helped a stranger by giving him her last ear of corn. The woman was weaving a basket as the man ate the corn, and when he finished the cob, another suddenly appeared in its place.

Realizing that the old woman must be Ngchuwessenna Chaskwen, the Corn Mother, he knew that if she stopped weaving, the world would end. So he summoned several wood mice to unwind her weaving every night.

“To this day, the mice continue to do this,” Fourbears said. “As long as there is respect between the spirits of males and females and those of the highest and lowest positions in life, the world will never end.”

“To this day, the mice continue to do this,” Fourbears said. “As long as there is respect between the spirits of males and females and those of the highest and lowest positions in life, the world will never end.”

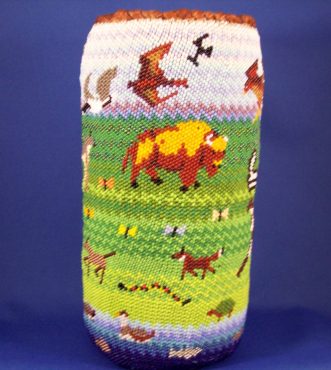

The story basket of Wanbli Hokshila — the Eagle Boy — came from her husband’s uncle Franklin Fire Shaker.

“I had a dream of Kansas with three beautiful horses — a roan, a white horse and a black horse. I saw a big basket in the background and the horses ran to the basket, then slowed down and went around the rim and turned into a design, with an eagle landing on the basket and a tornado,” she said. “The Eagle Boy and his three spirit horses protect the Plains People from tornados.”

Fourbears includes a story description with each basket she displays or sells. Sometimes the baskets are given as gifts at celebrations and others are meant to be given for healing. “Each basket has a spirit and there’s a tiny, tiny hole in the bottom of the basket where the spirit comes and goes,” she explained.

Fourbears includes a story description with each basket she displays or sells. Sometimes the baskets are given as gifts at celebrations and others are meant to be given for healing. “Each basket has a spirit and there’s a tiny, tiny hole in the bottom of the basket where the spirit comes and goes,” she explained.

In 2016, Fourbears published a book titled “Why the World Will Never End and Other Story Baskets.” Included are 13 of her basket stories from Delaware, Chumash, Lakota, Navaho, Ponca and other Native traditions.

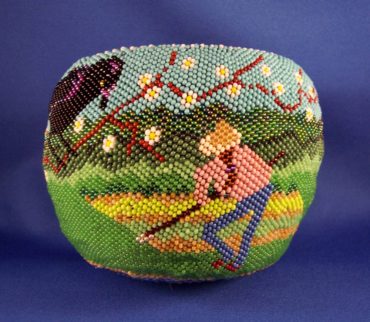

There’s also a photo and description of a basket inspired by a poem by local poet Mike Dillon as part of the Ars Poetica project. The poem, “In May,” spoke to her with its images of gardening and a crow watching from a hawthorn tree.

“When I read the poem, I could smell the salt from the bay and feel the dirt on my own hands in the garden and feel the presence of the crow,” she said.

“When I read the poem, I could smell the salt from the bay and feel the dirt on my own hands in the garden and feel the presence of the crow,” she said.

When she’s beading, Fourbears often works at her dining room table where she can look out at the headwaters of Miller Bay a few yards away. This winter, six eagles have taken up residence on the Fourbears’ land, two mature bald eagle pairs, a young bald eagle and a golden eagle — a visitor from east of the mountains.

“When we first bought this house and land, I was a little bit disappointed whenever the tide went out. But now I enjoy how everything changes and even the wildlife changes,” she said.

She always has music playing when she works. In her studio — a small blue building just a few steps from the house — she cues up a blessing song before she starts to work. It’s a song about the Four Directions: “From the direction of the west, the Creator is sitting there watching you. From above, The Great Mystery, Waha Tanka is watching you. Below, Grandmother Earth is watching you. As we sit on her lap, she’s cradling us.”

She always has music playing when she works. In her studio — a small blue building just a few steps from the house — she cues up a blessing song before she starts to work. It’s a song about the Four Directions: “From the direction of the west, the Creator is sitting there watching you. From above, The Great Mystery, Waha Tanka is watching you. Below, Grandmother Earth is watching you. As we sit on her lap, she’s cradling us.”

There’s a blossoming taking place among Native cultures right now,” she said. “And I’m honored to be part of it.”