It may be tough to put a finger on why one of Wanda Garrity’s pottery pieces calls to you. It’s the sort of beauty that just “feels right.” But listen to the Wauna artist explain it, and it becomes clear that her work is not about giving art meaning — but rather about making a statement.

“I’m looking to make a quality piece of art that someone would want to have in their house, rather than an interesting piece that’s fleeting,” Garrity says.

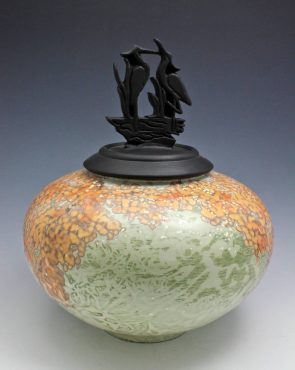

To achieve that goal, Garrity approaches her art as an architect, focusing on shape, form and balance. In fact, she often refers to herself as an architect rather than an artist.

“I put a lot of emphasis into the shape of the vessel to make the lines flow,” she says. “Most of my work is very precise… The shape of the pot is very intentional.”

And not just the shape of the pot. Garrity — who considers 75 percent of the work technical and 25 percent artistic — puts a great deal of time into experimenting with chemicals and glazes to achieve the exact effect she desires. It’s this quest for control that’s led her to cut back on raku and focus more on other firing techniques.

“Raku is too elusive,” she explains.

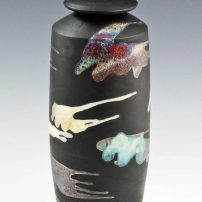

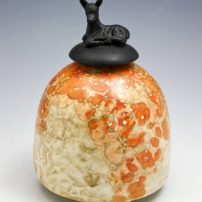

Garrity’s pottery styles include saggar, carbon (known to most people as horsehair) and high-fire (which she usually reserves for art fairs or special events, like the upcoming Greater Gig Harbor Open Studio Tour.)

The high-fired technique, she explains, is used for functional pottery because it makes it more durable. The downside is the limit of glaze colors — which are generally earth tones and less bright.

Most of her low-fired pots have lids, which she makes from clay and often adds driftwood, stones — anything that inspires her. This is where the artist side of her gets to let go.

“The lids is what makes me different (as a potter),” she says.

‘Hobby’ as Stress Relief

‘Hobby’ as Stress Relief

Garrity’s pursuit of precision could perhaps be explained by her previous career: 29 years in the Air Force. Originally a linguist, she later became a supply officer and handled logistics.

That career is also responsible, in a way, for her path as an artist as well as for her move to Washington state from her last post, in Hawaii.

“I had a stressful job and I needed something to take the stress away,” Garrity says.

She’d taken a pottery class as a teen in Spokane — where she hails from originally — so in 2000, she came back to the idea and found a six-week class on the Air Force base. But those six sessions weren’t quite enough, so Garrity discovered a more long-term opportunity at the nearby Army base.

It didn’t take long for the Army base arts center to ask her to volunteer as well as teach classes — a commitment she carried through her retirement, as a lieutenant colonel, in 2004.

Since she turned down an offer for a civilian contractor job on base in Hawaii (it would have been just as stressful, she says), she needed a fallback plan. Pottery made sense. As did moving to the Puget Sound region, a place she fell in love with while stationed in the ’80s at what was then known as McChord Air Force Base.

Since she turned down an offer for a civilian contractor job on base in Hawaii (it would have been just as stressful, she says), she needed a fallback plan. Pottery made sense. As did moving to the Puget Sound region, a place she fell in love with while stationed in the ’80s at what was then known as McChord Air Force Base.

Fireblaze Pottery was born in Port Orchard shortly after the move, and Garrity made the switch to being a full-time artist, even as she thought of pottery as a hobby.

“It’s a hobby that pays for itself and has brought me fulfillment,” she says.

Especially so because moving around every few years in the military meant she never got to see her own projects come together from beginning to the end.

Especially so because moving around every few years in the military meant she never got to see her own projects come together from beginning to the end.

“Now, I see every piece from start to finish,” she says.

The “hobby” has paid for itself and them some. Thanks to the success of Fireblaze Pottery, she’s been able to do things like travel every few years back to Hawaii to participate in the Raku Ho’olaule’a retreat, where potters get together to create work and get it judged. It’s where Garrity learned some of her techniques back in her military days.

In 2012, she won the grand prize at Ho’olaule’a, and two years ago was the guest artist.

“It was a full circle, to start there and be asked to come back as a guest artist,” she says.

A Self-Taught Artist

Except for the classes on the military bases and the occasional workshops, Garrity is self-taught. But it was that experience in Hawaii that shaped her (no pun indented) as what she describes as a “tight potter,” one whose vessel shapes are precise.

As a volunteer and instructor, her work revolved around throwing. She’s gotten so good at it now that some pots take her less than 10 minutes on the wheel.

“I love to throw. It’s cathartic. It’s mesmerizing,” she says. “All the world goes away and I can’t think of anything else.”

“I love to throw. It’s cathartic. It’s mesmerizing,” she says. “All the world goes away and I can’t think of anything else.”

The process requires her full focus. And not only does she focus her entire body to “feel” what she’s doing, but she also uses a mirror to observe.

Having perfected the throwing part, Garrity can focus more on the next stage of the process. If she plans to use the saggar or carbon technique, that means coating the vessel first with terra-sigillata, an ultrarefined clay slip, then buffing it and bisque-firing it.

For saggar, she’ll use chemicals after that to coat the pottery and then wrap it in foil with leaves, feathers, horsehair or other combustible materials.

“It can still be trial and error with some chemicals so I’m always testing things,” she says. “I can control most of the design with saggar except when I use copper wire, so I’m still experimenting with that.”

The carbon pottery’s unique design comes from the use of things like feathers, sugar or hairs from animals (most typically horses, dogs, cats and lamas). It’s especially popular for commissions, as customers like to bring hair from horses or other animals to memorialize them.

The carbon pottery’s unique design comes from the use of things like feathers, sugar or hairs from animals (most typically horses, dogs, cats and lamas). It’s especially popular for commissions, as customers like to bring hair from horses or other animals to memorialize them.

Now that Garrity has cut back on the number of shows she does and the galleries that sell her work, she can focus more time on each piece and on more experimenting. She’s also cut back on teaching to only offer private classes, though she does continue to volunteer as an instructor at the Washington Corrections Center for Women in Purdy.

Now that Garrity has cut back on the number of shows she does and the galleries that sell her work, she can focus more time on each piece and on more experimenting. She’s also cut back on teaching to only offer private classes, though she does continue to volunteer as an instructor at the Washington Corrections Center for Women in Purdy.

Garrity also has a bigger project in mind: a new studio. She and her husband recently moved from Port Orchard to a new home on the Key Peninsula, just minutes from the Purdy Bridge. Her current workspace — converted from part of a garage — is a bit cozy and doesn’t have room for her display shelves.

The freedom to create what she wants, rather than what the galleries want to sell, also means she can evolve as an artist on her own terms. In her case, that means sculpting more and altering shapes.

“I want to make each piece more of a statement,” Garrity says. “To me, leaving a mark makes me feel like I matter — and it’s satisfying.”