When a renowned Hall of Fame martial artist wanted to capture the story of his life in a sculpture, he turned to Tom Carmichael. A Bremerton metal artist who’s known mostly through word of mouth (forget finding him online, for example), Carmichael created the most awesome piece, using bits and pieces of the customer’s life as inspiration. The end result: a bronze, oak-tree sculpture valued at about $100,000.

When a renowned Hall of Fame martial artist wanted to capture the story of his life in a sculpture, he turned to Tom Carmichael. A Bremerton metal artist who’s known mostly through word of mouth (forget finding him online, for example), Carmichael created the most awesome piece, using bits and pieces of the customer’s life as inspiration. The end result: a bronze, oak-tree sculpture valued at about $100,000.

“It’s the story of his life,” Carmichael says.

To create that story, the artist shaped the base of the tree like the nation of China, the martial artist’s native country. The tree had two parts, symbolizing the customer’s personal and professional life. The symbolism-rich piece included martial art stances in its design as well as a broken branch for a broken marriage. The leaves represented the many people who touched the owner’s life.

In his own words, Carmichael says he “had to compose” the sculpture. It’s a simple description for a piece of art that requires such deep insight. Yet despite this work — and many other art pieces he’s “composed” over the last decade or two, including some that were displayed at the Tacoma Art Museum, Carmichael doesn’t exactly see himself as an artist.

In his own words, Carmichael says he “had to compose” the sculpture. It’s a simple description for a piece of art that requires such deep insight. Yet despite this work — and many other art pieces he’s “composed” over the last decade or two, including some that were displayed at the Tacoma Art Museum, Carmichael doesn’t exactly see himself as an artist.

“I don’t think I have a specialty… I just do things,” he says. “I never considered myself an artist, I just know how it’s done.”

“I don’t think I have a specialty… I just do things,” he says. “I never considered myself an artist, I just know how it’s done.”

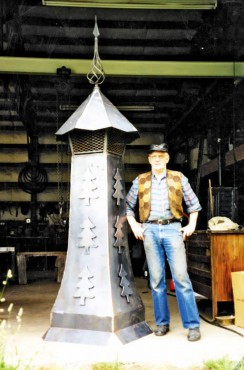

His shop, next to his home on the Tracyton waterfront, indeed speaks more to that “know-how” side of Tom Carmichael than it does to his innate ability to capture slices of life in metal. Filled with every possible metallurgic widget imaginable, the shop is cluttered with various machines, many of which he built himself to aid in the creation of a certain piece.

Take a recent project, for example — a weather vane with a fish leaping out of water. Carmichael needed to make something out of steel that would look like splashing water. He fabricated a die and puncher in no time for cutting out circles. When he realized the circles were too rough, Carmichael devised a tumbler to smooth them out.

That’s how it goes in Carmichael’s shop — part engineering ingenuity, part graceful art, his metal works are the result of both highly technical inclinations and a keen eye for beauty. And before he even cuts the first piece of metal, Carmichael does extensive research. In the case of a gorgeous gate depicting herons surrounded by cattails, for example, he studied how the cattails grow in their native environment to make them look lifelike.

That’s how it goes in Carmichael’s shop — part engineering ingenuity, part graceful art, his metal works are the result of both highly technical inclinations and a keen eye for beauty. And before he even cuts the first piece of metal, Carmichael does extensive research. In the case of a gorgeous gate depicting herons surrounded by cattails, for example, he studied how the cattails grow in their native environment to make them look lifelike.

Betty Fabry, one of his customers, recalls the many hours he spent pouring over books after she’d asked him to make a weather vane depicting a sailing ship, a tribute of sorts to her husband’s longtime Navy career. Fabry had given him a photograph with the ship she wanted made, and after doing his own research, Carmichael called to say the image wasn’t accurate. “He wanted it to be just perfect,” she says.

Betty Fabry, one of his customers, recalls the many hours he spent pouring over books after she’d asked him to make a weather vane depicting a sailing ship, a tribute of sorts to her husband’s longtime Navy career. Fabry had given him a photograph with the ship she wanted made, and after doing his own research, Carmichael called to say the image wasn’t accurate. “He wanted it to be just perfect,” she says.

The weather vane was so beautiful, it exceeded the couple’s expectations. “It was so pretty, we almost didn’t want to put it up on the top of the house,” she says. “We were just so impressed.”

The sentiment is common for Carmichael’s customers. He likes to tell the story about one customer, long ago, who was “exceedingly pleased” about the work he’s done, and that became his new standard. He tells his customers about it, and frequently receives thank-you letters from them assuring him they were “exceedingly pleased.”

One couple wrote a letter about the gates he created for them, and they used about a dozen adjectives to describe their elation. “The gates you made us are intricately beautiful and will be forever enduring,” the letter said. “We are, of course, superlatively… immensely, enormously… gigantically, colossally… stupendously and far, far away beyond exceedingly pleased.”

One couple wrote a letter about the gates he created for them, and they used about a dozen adjectives to describe their elation. “The gates you made us are intricately beautiful and will be forever enduring,” the letter said. “We are, of course, superlatively… immensely, enormously… gigantically, colossally… stupendously and far, far away beyond exceedingly pleased.”

The Mechanics of the Work

Carmichael’s path into works of art seems accidental. But his mechanical genius had an early start. Growing up on a farm in Hoytsville, Utah (where his great-grandfather was one of the town’s founders and an early Mormon pioneer), he was about 14 when he invented his first gizmo, a machine that could precisely measure the amount of poisoned grain that would be poured into a hole for rodent control. He actually tried to patent the widget but was denied because another item — a sugar bowl, of all things — already had a patent on the same idea.

By the time he was a young adult, Carmichael had built and repaired steam engines, and he paid his way through a six-month college machining course by doing electrical and plumbing work for the school. He did a few stints as a gold miner, logger, then ore miner before being drafted into the coast artillery for six months during World War II, then decided to enlist into the Army Air Corps, which sent him to mechanic school.

By the time he was a young adult, Carmichael had built and repaired steam engines, and he paid his way through a six-month college machining course by doing electrical and plumbing work for the school. He did a few stints as a gold miner, logger, then ore miner before being drafted into the coast artillery for six months during World War II, then decided to enlist into the Army Air Corps, which sent him to mechanic school.

Carmichael never got to fly in the military, but he did get to teach flight engineering. When the war ended, he landed a job in Texas at Slick Airways, which turned surplus war planes — Curtiss C-46s — into civilian cargo planes and became the largest scheduled freight carrier during its era. His next job was at Howard Aero, another major aircraft company that did the same type of work. He recalls one customer who wanted a plane that would fly from Mexico to New York City nonstop, 300 mph with 10 passengers — a job that the crew including Carmichael pulled off by using a WWII plane and pretty much redoing every piece.

Eventually, he moved to a new company, making Lear jets, a fond time when he recalls being “king of the shop” as an independent contractor.

Eventually, he moved to a new company, making Lear jets, a fond time when he recalls being “king of the shop” as an independent contractor.

By 1973, Carmichael left the aircraft industry but his mechanical engineering and steel fabrication work continued. He’s created all sorts of things, from moving trailers to machines for sheering holly trees, and at one point did millwright work for the city of Seattle. His latest invention, a mechanical folding roof perfect for spaces that contain garbage dumpsters, is a product he hopes will go full-force in the near future after marketing.

While he continues to offer his highly specialized technical skills to those who inquire, it’s Carmichael’s metal art — bronze, aluminum, silver, zink, whatever the project dictates — that inspires the most awe. Some of the pieces could be seen while you drive around Kitsap County: an iron gate depicting moving horses, another with a scene of a fallen tree and three herons feeding in a swamp with cattails.

While he continues to offer his highly specialized technical skills to those who inquire, it’s Carmichael’s metal art — bronze, aluminum, silver, zink, whatever the project dictates — that inspires the most awe. Some of the pieces could be seen while you drive around Kitsap County: an iron gate depicting moving horses, another with a scene of a fallen tree and three herons feeding in a swamp with cattails.

He does the work, as he describes it, “from scratch.” Much like a sculptor who visualizes a beautiful artpiece in a hunk of raw wood, Tom Carmichael imagines a graceful sculpture when he looks at a sheet of metal. “I use a lot of savvy from one industry and move it into another,” he says. “People come to me because they know I can do it. I like the challenge.”