(Photography courtesy Marcelo Verfe/Pexels)

Late-night talk show hosts Johnny Carson and Jay Leno called it the worst Christmas gift ever. NASA thought it was good enough for astronauts. Emily Dickinson packed it with half a pint of brandy (and 19 eggs) and gifted it to her delighted neighbors. British royals have turned it into an elaborate, grandiose part of their weddings — a tradition passed from one generation to the next for centuries.

Hate it, joke about it, regift it and use it as a doorstop all you want, but fruitcake is a lot more than a humble Christmas present. One might even say it’s a heavenly treat. Just ask the monks who bake it as a source of income at Holy Cross Abbey in Virginia and Assumption Abbey in Missouri.

From Windsor Castle — where Queen Victoria’s wedding fruitcake pioneered today’s wedding cake design (and caused a media frenzy) — to a 1910s Antarctic expedition, from auction houses to outer space, the adventurous fruitcake has seen it all.

Turns out, this all-too-often-misunderstood confection has seen some unlikely exploits throughout history. If these escapades don’t compel you to give fruitcake an elevated status, you might at least end up admiring — and perhaps even envying — the amazing adventures of this unassuming treat. After all, what other culinary curiosity is so ubiquitous across cultures and has received equal attention among royalty, scientists, U.S. military researchers, collectors and ordinary citizens alike?

And let’s not forget that fruitcake might outlive us all, thanks to its famed longevity. Two century-old confections — a 176-year-old slice of Queen Victoria’s cake that fetched nearly $2,000 at a Christie’s auction in 2016 and the 100-year-old fruitcake unearthed in the Antarctic in 2017 — both looked (almost) good enough to eat.

A Brief Lesson in History and Culture

Like so many other important inventions, such as concrete, highways, bound books and the modern legal system, fruitcake began its journey in Ancient Rome. At least according to culinary lore, which claims that the Romans’ satura — the original energy bar? — was the grandfather of fruitcake. Made from barley mash, raisins, pine nuts, pomegranate seeds and honeyed wine, satura fortified Roman soldiers during extended battles.

It’s uncertain what the fruitcake was up to for a few centuries after that — until after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Thanks to a wider availability of dried fruits and nuts during Middle Ages in Western Europe, the fruitcake got a reboot to a version that’s closer to the one we love (or don’t) today.

Once refined sugar became available to the common populace shortly after, the fruitcake became unstoppable. Not counting a short ban in 18th-century Europe for being “sinfully decadent,” this indulgence steadily trekked across nations and continents.

From Italy’s panforte (and later panettone) and Germany’s stollen or Christollen, to Chile’s pan de pascua and India’s kerala plum cake, fruitcake has galivanted its way into feasts around the planet — and eventually beyond. The recipes may vary according to local ingredients and customs, but once you see or taste it once or twice, you’ll likely recognize the globe-trotting fruitcake by any other name, anywhere.

Worthy of Kings and Queens

Fruitcake’s journey to today’s Christmas table was not without mischief. It all started in 1840 with Queen Victoria’s wedding to Prince Albert.

By then, fruitcake (known as English plum cake, not to be confused with plum pudding) was a royal wedding tradition in Great Britain. However, it had been, in the words of Victorian scholar Emily Allen, “a rather low-lying affair, made up of a single layer of rich fruitcake covered in a thick coating of almond paste and encrusted with white sugar icing.” In contrast, Queen Victoria’s was a 14-inch-tall, 10-foot-wide, 300-pound, three-tiered affair.

Described in an 1840 journal by an illustrator as a “great beast of a plum cake,” it made a statement with both its size and intricate, “carved” ornamentation. According to a 2003 article by Allen in the journal Victorian Studies, the sight of the cake-in-progress attracted a mob to the bakery, where a policeman had to be posted at the door.

The media became highly preoccupied with the cake for a week preceding the matrimony, and drawn-from-life portraits of the confection “hung in every printshop in London,” Allen wrote. Local newspapers also published images of the cake — and every royal wedding cake ever since.

(Photography courtesy Kevin Ho/Wikimedia Commons)

This sensation, however, launched more than the modern tabloids’ (and commoners’) obsession with all things royal. Brides everywhere owe Her Majesty their gratitude for having premiered one of the world’s first wedding cake toppers. After all, a wedding cake without a topper is —well, just a cake. Plus, how would the bride and groom celebrate their one-year anniversary if they didn’t have a top cake layer to freeze for the occasion?

As for the royals, the tradition of highly elaborate, lavish wedding fruitcakes lived on, at least until Prince Harry and his bride, Megan Markle, broke it off in 2018. According to The Royal Household’s website, the couple opted for lemon elderflower cake. But — considering that slices of Queen Victoria’s cake are still around (hence the Christie’s auction) — don’t expect the royal fruitcake to exit quietly into the night.

Not So Much for Astronauts

Speaking of the stars, the fruitcake’s brush with space exploration was a much quieter (and more short-lived) experience — though one could argue just as monumental.

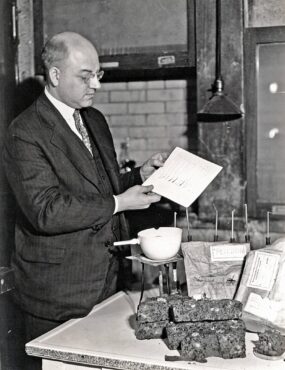

In the late 1960s, NASA needed a contingency ration for space flights. The agency asked the U.S. Army’s Natick Research and Development Laboratories in Massachusetts to develop a product that maintained 100% of the 1968 recommended daily allowance and “consumer acceptability under ambient storage conditions for three years.”

Developing a single-food, flexibly packaged contingency ration that could meet consumer acceptability, storage stability and nutrition requirements was no small feat. But NASA came to the right people: Natick researchers had already created the Army’s famed Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE), which included thermoprocessed cakes, as a combat ration.

According to a Natick Laboratories 1981 technical report, the lab used soy concentrate to boost the protein content of several experimental cakes. Fruitcake won NASA’s approval over choices like cherry nut and chocolate nut cakes. It wouldn’t be the fruitcake’s first sojourn into space, either. Dehydrated fruitcake was part of space food at least as far back as the Apollo 10 and 11 missions in the ‘60s (sadly, many of those rations landed back on Earth, uneaten).

The lab prepared 390 fruitcakes fortified with a variety of vitamins and minerals (calcium, vitamin C, etc.) and 388 unfortified portions, and froze them in three lots at different temperatures, either for one year or three.

At the end of each duration period, 36 “untrained consumers” performed blind taste tests on the samples. The testers concluded that the prototype tasted “acceptable” — perhaps as good as most people would expect of fruitcake. The experiment was a success: The consumer ratings were similar for both versions, and the fortified variety retained its nutrient quality. Thus, the humble fruitcake began its space mission.

Offered up during a joint Apollo 17-Soyuz feast at the International Space Station, the fortified fruitcake received the astronauts’ thumbs up. NASA then approved it for consumption during the following year’s Christmas Day as a holiday treat and placed it on shuttle flight menus.

Alas, this out-of-this-world triumph didn’t last long. A two-year follow-up study on an adjusted formulation determined that fortified fruitcake was not an “adequate carrier” for three out of the nine supplements. Fruitcake’s mission-critical days were over. Regardless, hikers continue to swear by it as one of the best nutrient-packed snacks for long-term hikes.

What’s Next for Fruit Cake?

It’s hard to beat space travel as far as bragging rights go. Unless we’re talking (near) immortality. Fruitcake may have only proven to last for over a century so far, but its notoriety may just make up for the rest.

Sure, the oldest surviving piece of fruitcake is not as old as the 4,000-year-old millet noodles found in a river in China. But can those noodles claim an entire “National Day” named after them? (National Fruitcake Day is on Dec. 27 this year if you want to celebrate.) Are any cities fighting to be called the Noodle Capital of the World, like Claxton in Georgia and Corsicana in Texas, who are battling for the Fruitcake Capital of the World title? Does any Chinese family preserve millet noodles as their family heirloom, like Michigan’s Ford family does their 1878 slice of fruitcake? Have any vintage noodles been carefully displayed in museums, like fruitcake has at the Smithsonian Institution and the Brooklyn Museum? And this, by far, is not fruitcake’s complete bucket list.

Who knows where this prolific traveler will turn up next? Fruitcake may not be destined for space — and possibly not even for your dinner table. But one thing is clear: This unappreciated loaf deserves a little bit more respect. Perhaps it simply needs the right recipe, one worthy of its historic stature.

(And if you’re curious about the longevity part, here’s one of the “secrets”: booze.)