When John Jewell retired from a career of more than 30 years in education, he knew he “wanted to do art.” He’d been gradually taking art classes — starting out as something to do with his daughter.

He knew he had found a new passion. What he didn’t know is where that passion would take him. Although he still considers art his “hobby,” Jewell has created many bronze sculptures that are displayed around the country, from public places to private collections.

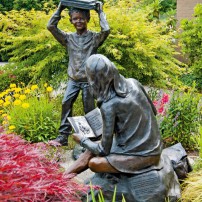

“I like to capture emotions and relationships,” he says.

One of those captured emotions is deeply personal. Among Jewell’s first sculptures is that of a premature newborn. The baby, Alice Rose, is his granddaughter, who was born in 2000 at 28 weeks, weighing 2 pounds, 4 ounces. Her mom had to be rushed for a total of 40 miles by snowmobile, bus and boat from Lake Chelan to Wenatchee, then flown to a Seattle hospital.

Alice spent two months in the hospital and Jewell, by then retired, went to see her regularly. For a while, the baby couldn’t even be held.

“It was such an emotional time, looking at her and seeing how beautiful she was,” Jewell says.

He captured the experience in a real-size sculpture of the baby. Hands coming out of the rock represent all the people who helped Alice Rose survive — from the park service rangers and paramedics, to the friends and strangers across the country who prayed. (Today, Alice is a healthy, lively 15-year-old.)

A visit to Jewell’s home in Vaughn reveals several other private moments captured forever in clay or bronze — such as two generations of the family dancing upon learning the news of pregnancy.

The collection — spread around the house, the garden and his studio — gives a glimpse both into Jewell’s passion for three-dimensional portraits and into his professional work. Several maquettes (miniatures of real-size sculptures) are a testimony that Jewell is more than modest when he calls his art a hobby.

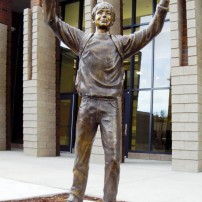

Among his publicly displayed sculptures are those of Meriwether Lewis with his dog and Sgt. John Ordway of the Corps of Discovery, displayed at the entrance to Fort Lewis; first Puget Sound teacher, Chloe Clark, at the elementary school named after her in DuPont; and a fireman statute at West Pierce Fire & Rescue headquarters that commemorates Sept. 11 (the sculpture is part of Memorial Park, which also has one of the pieces of steel from the World Trade Center).

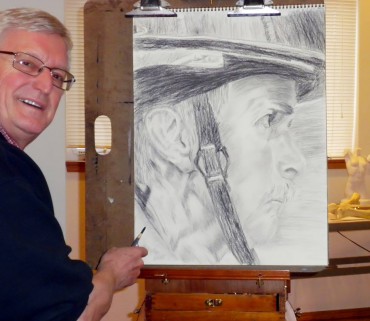

Although Jewell has cut back from public art — focusing more on doing art with kids, including his four grandkids — he continues to be drawn to portraits. These days, they are mostly two-dimensional: Jewell, who developed a knack for drawing after he started sculpting, visits a retirement home every Friday and hires a person to pose for a charcoal portrait.

Meticulous Authenticity

One of the things that Jewell’s drawn and sculpted portraits have in common is his way of studying the person carefully — whether a live model or a historic figure.

“The more you know about a person, the more they change physically,” he says. “You start perceiving them differently. You end up capturing maybe a little smile or a twinkle in their eye or their inquisitiveness.”

For the Sept. 11 sculpture, Jewell insisted on his model being an actual fireman with a lot of experience.

“Firefighters carry themselves in certain ways, communicate in certain ways,” says Jewell, who has studied anatomy extensively. “You can tell the difference.”

When he worked on the Chloe Clark sculpture, Jewell even studied authentic period clothing from the collection of the Washington State History Museum (he had to wear white gloves due to the delicate nature of the fabric).

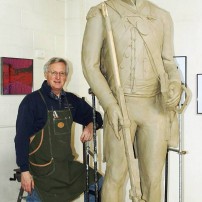

But the most intensive research came when he worked on the Lewis and Ordway sculptures (the two pieces were commissioned separately, and together took about three years to complete).

For the 14-foot Lewis piece, every detail had to look authentic, from the eagles on the uniform buttons and the feather in the hat, to the Newfoundland, Seaman. Jewell read numerous books about Lewis. He also worked directly with researcher lan Archambault, then curator of the Fort Lewis Military Museum, who solicited extensive input from many Lewis historians across the country.

Seaman was quite the challenge. Newfoundlands of the era looked differently than modern ones. In addition to working with the Seattle Newfoundland Society and reading a book by an author who studied dogs through history, Jewell received input from veterinarian and fellow Key Peninsula artist Robin Peterson.

“I sculpted it without the fur and she made sure the muscle and bone structure was right,” he says.

Before he worked on Ordway — who was the third in charge on the Lewis and Clark expedition and the only person to keep a daily journal of the trek — Jewell visited Ordway’s birthplace. He met some of the local residents and took the opportunity to “feel” the land.

“It gives you a fuller appreciation of the person,” he says.

Even after all the deep research at the time, however, he says there was more left to learn.

“It’s a learning process. You keep learning as you go along,” he says. “If I did it over again, it would be different again.”

Always a Teacher

These days, Jewell is more likely to be found in the kindergarten classroom of his daughter, Laura Stafki, who teaches at Minter Creek Elementary. He volunteers regularly, and after school frequently helps Stafki’s Girl Scout troupe with art projects at his home.

Jewell, who has a doctorate degree in special education, began his career as an elementary school teacher. He eventually became an administrator, with his last job as an elementary school principal in Steilacoom.

Education runs in the entire family. His wife, Andrea, was also an educator for nearly 30 years. For a while, she and Stafki taught in adjacent classrooms at Vaughn Elementary School, where Jewell began his classroom-volunteer service.

“He found out that sculpting was lonely, so he started volunteering at Vaughn,” Andrea says.

Now, Stafki teaches in the same building as her teacher husband, Jeff. The Jewells are still passionate about education, as it becomes obvious when the subject comes up.

Jewell currently has a project on hold for the Tacoma General Hospital’s nursing association (pending fundraising). Like with much of his other work, this one, too, has a connection with history. It’s one of the things that move Jewell — compelling him to take on a new project (he has turned down several).

“I’m interested in furthering the values people have and relaying things that make people and communities,” he says. “I’m interested in doing the kind of things that elevate the human spirit.”