When longtime Bainbridge Island resident Cynthia Sears had a vision a decade ago to build an arts museum on the island, she met a lot of skepticism. Start with a collection, many advised her, and then explore the feasibility of a building.

But Sears was undaunted. She wanted to create a platform for local and regional artists who are less known — and she knew there was a niche to fill.

“People said it was a mistake to start with the building first,” Sears says. “One reason we didn’t do a feasibility study was because I knew it wouldn’t look feasible at the time.”

Today, no one would argue that the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, not quite two years old, is a prominent cultural and community landmark. Since its opening, the museum has received more than 130,000 visitors — a busy pace for its size.

The translucent building, located at the corner of Winslow Way and State Route 305, is one of the first things visitors from the Seattle ferry see when they arrive. Even without entering the building, pedestrians can get a glimpse of the life inside.

“The building is transparent because Cynthia wanted it to be accessible,” says Matthew Coates, principal architect with Coates Design Architects who led the design of the project and was heavily involved in the capital campaign.

“I didn’t think we could get away with it at this corner because it’s the most prominent corner on the island,” he says. “In a way, you become a participant in viewing the art whether or not you enter the building.”

Giving Voice to Local Artists

Sears was inspired to spearhead the effort after seeing local artists’ works at galleries and wanting to learn more about them.

“There was no place to see the work of these extraordinary artists, all of whom lived right here, and it frustrated me,” she says.

As she gathered supporters, she shared her vision for creating a platform for less-known artists. That vision became the cornerstone for Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, whose goal, over the years, is to show a diverse profile of exhibits that includes emerging as well as master artists, along with a diversity of themes.

“The thing that is very exciting for all artists in the Northwest is that they are highlighting a great range of artists and curating it in a way that allows the art to speak,” says Woodleigh Marx Hubbard, whose collection of works was featured recently in a group exhibition that included original paintings and drawings of children’s book illustrators.

Hubbard, who lives on Bainbridge Island, has received many awards for her books (some of which she writes too). She has published about 20 books, and some have been translated in several languages. Hubbard’s work had been featured on National Public Radio and on Reading Rainbow.

Despite her international success, she has not shown her work for about seven years. The Bainbridge exhibition was her first return into the public eye.

“This is a collection of work I have not seen as one body ever — I feel like I’ve done something,” she says. “This museum has really gifted me one of the happiest years of my life.”

Larry Ahvakana, a Suquamish master artist, also saw the invitation by the museum as an opportunity to show a large collection of his work — something he hadn’t done since the ’80s. A professional artist for more than 30 years, he works with a broad range of materials, including wood, stone, glass, ivory and metal.

Ahvakana is a nationally renowned sculptor who’s had art included in major museums and private collections around the world. At the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, his recent exhibition reflected more than 20 years of work.

“(Being exhibited) validates your energy and direction at being an artist — it validates your efforts and involvement in the arts,” he says.

Born in Alaska, Ahvakana draws his inspiration from his native Inupiaq culture. The museum sought him out for its Cultural Diversity Series, sponsored by the Ames Family Foundation.

“I was really intrigued by the globality of his work, and it’s all exceptional work,” says Greg Robinson, executive director and curator.

Making Art Accessible

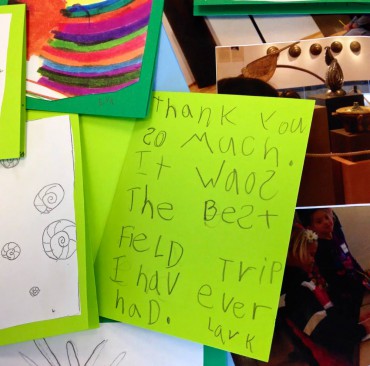

One of BIMA’s primary goals is to make art — and artists such as Ahvakana and Hubbard — more accessible to the public. That’s why artist events are scheduled regularly, both for the general public and for school groups. A dedicated classroom space is used for children’s hands-on activities that are tied to current exhibitions and often include meeting one of the artists.

Bringing in artists “is a chance to make art more personal,” Robinson says. Plus, it’s an opportunity to inspire new generations of artists.

The concept of accessibility is supported not only by the design of the building, but also by the free admission. BIMA members and donors make the free admission possible — and it’s something that the board of directors for the nonprofit museum envisioned from the beginning, Sears says.

“It’s a service to the community rather than us being in a financial position (to do it),” Robinson says. “We’ll be fundraising forever.”

Eco-Friendly Building

As an educational institution, the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art offers a variety of activities, from film screenings in its auditorium to classes and field trips. But there’s another, perhaps less considered, educational component: the building’s sustainable features (as well as tours focused on the eco-friendly aspect).

The museum was built to U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED Gold specifications (certification is expected any time). If certified, this will be the first art museum in the state with a LEED Gold certification.

The museum was built to U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED Gold specifications (certification is expected any time). If certified, this will be the first art museum in the state with a LEED Gold certification.

“Energy efficiency was not a small feat because museums are energy intensive and have strict humidity and temperature controls,” Coates says.

The green features include, among other things, a 60-module solar array on the roof; a geo-exchange system with 14 underground bores designed to reduce heating and cooling energy; and automated, hollow-aluminum louvers for the curved glass façade. An onsite water filtration system helps divert pollution from the Winslow Ravine, a green space that comprises as much as 43 percent of Island Gateway, where the museum is located.

Community Jewel

The combination of the architecture and sustainable features is what first attracted Martina Moores, who is one of the museum’s 150 volunteers and 55 docents. She was intrigued as she watched the building construction when she moved to the island two years ago.

Moores, who grew up in Vienna, loves art and museums. She says the peaceful and relaxing atmosphere of the museum, surrounded by art, is a great place for people to return to, especially in today’s hasty world.

“We have so many local residents come again and again to experience it,” says Moores, who volunteers once a week as docent and is also part of the installation crew. “It’s a nice addition to the island and a place for people to get together and enjoy.”

To facilitate the idea of getting together, BIMA’s lobby was designed with events in mind. Robinson says the space fills a need for nonprofits looking to host functions. The lobby is also home to a popular bistro, which serves local, artisanal foods; coffee; wine and beer.

The Bainbridge Island Museum of Art has become a destination for locals and visitors alike — half of the visitors come from outside of the Kitsap Peninsula. In its short year and a half of existence, it has already gained national reputation: Travel + Leisure magazine included it on its list of 16 of America’s best small-town museums in June 2014 and Fodor’s Travel recently named it one of 15 best small-town museums in the country.

It took about a decade for BIMA to evolve from an idea and into a cultural and community landmark. Sears, who first envisioned this space two decades ago, could not be more pleased that she didn’t listen to naysayers and pressed on to get a building before a collection.

“I could not articulate (at the time) what I had in mind, I wanted the possibility to be there,” she says. “We could not do what we do without the building.”