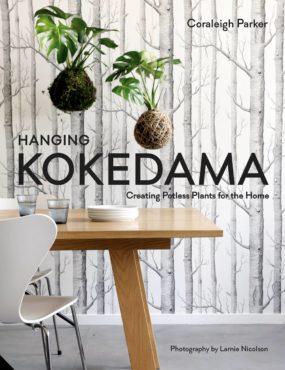

Editor’s note: This excerpt is adapted from the newly released book, “Hanging Kokedama: Creating Potless Plants for the Home” by Coraleigh Parker.

Editor’s note: This excerpt is adapted from the newly released book, “Hanging Kokedama: Creating Potless Plants for the Home” by Coraleigh Parker.

A variant of bonsai, kokedama is the Japanese art of creating potless plants using a unique soil mixture, moss and string.

There is something intrinsically inviting and soothing about the form of kokedama, through the juxtaposition of its controlled and wild aspects. It is a manifestation of wabi-sabi, or the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection. All the elements that keep bonsai from falling into obscurity are also present in kokedama, but in a much more accessible format.

Economical design, which seeks to use a minimum of components, along with displaying natural processes and naturally occurring objects, is becoming increasingly mainstream. As more people choose to see the beauty in the roughness of nature, the room in their lives for meaningless clutter diminishes.

As a hobby, the art of making kokedama is as rewarding as it gets. The act of putting our hands in direct contact with natural materials literally grounds us.

The wrapping process is very meditative; the action requires bilateral coordination — that is, to use both hands simultaneously and independently. And because both hands are required to wrap, and each must perform separate and independent actions, it is very difficult to think about anything else. One becomes completely present in the moment.

Additionally, when creating the heavily wrapped style, there is a meditative quality to the repetitive but nuanced action of wrapping string around a sphere. It is almost hypnotic.

Additionally, when creating the heavily wrapped style, there is a meditative quality to the repetitive but nuanced action of wrapping string around a sphere. It is almost hypnotic.

Many amateur kokedama artists use the art as a way to unwind after hectic days at work or frenetically busy periods in their lives. The action of making a kokedama provides a small haven of tranquility and peace that centers one’s energy back into the body and self.

Kokedama evolved from the nearai style of bonsai, which has exposed roots as part of the aesthetic. Normally they are grown in a pot for such a long period of time that their roots completely fill the pot and they can be removed and displayed without harming the tree. To stop the roots from drying during the transformation or root aging process, moss is placed over the roots to cover and protect them.

The traditional form of kokedama is created using a mixture of peat and akadama soil turned into a sphere. This is split and hollowed out in the center.

A small plant with its roots wrapped in sphagnum moss is inserted and the two halves are joined again. Sometimes the outside is seeded with grass or wrapped with wild woolly moss.

The more modern method is to leave out the clay-based akadama soil altogether. The best style to learn with is to simply wrap the roots and soil in a thick layer of sphagnum moss. This provides a container to hold in the moisture and reduce the amount of watering needed. The moss is like a dense sponge; it holds the water and releases it slowly back to the roots. It also prevents evaporation of moisture from the soil, as would normally occur with a pot.

The more modern method is to leave out the clay-based akadama soil altogether. The best style to learn with is to simply wrap the roots and soil in a thick layer of sphagnum moss. This provides a container to hold in the moisture and reduce the amount of watering needed. The moss is like a dense sponge; it holds the water and releases it slowly back to the roots. It also prevents evaporation of moisture from the soil, as would normally occur with a pot.

The main difference though between a pot and a kokedama is the way the roots respond. Roots essentially adhere to one type of behavior, which is to seek water. The root activity is binary: As a very general rule, if there is water, they grow — if there isn’t, they don’t. (This is a topic that some scientists dedicate years to, so take with a pinch of salt.)

What this means in a pot is that the roots always encounter water so they continue to grow. They grow and grow, around and around the inside of the pot until they exclude any moisture or nutrients from entering.

In a kokedama, however, the roots that come to the outside of the ball encounter air. If the air is dry, the roots stop growing. Instead of using long, fat roots to explore for water, the plant grows many fine roots within the ball.

In a kokedama, however, the roots that come to the outside of the ball encounter air. If the air is dry, the roots stop growing. Instead of using long, fat roots to explore for water, the plant grows many fine roots within the ball.

With some plants, such as trees, the size of the canopy is determined by the size of the root mass. As this is defined by the size of the ball, trees will stay as small examples of their larger, wild counterparts.

You will probably gain more pleasure from your kokedama and observe their needs best if you assume that plants are people too: Try to love them like you would a friend or a pet. Get to know your plants. Don’t expect them to give you something for nothing.

All relationships are about give and take. When you give your plants the attention they need, they will happily reciprocate by giving you beautiful, green goodness to look upon. They will gladly fill your life with tranquility and peace.

Curating kokedama

Curating kokedama

Kokedama are perfect for completing a space because they are so versatile. They can be made in any size, shape or color to suit the setting.

Suspended kokedama add depth and texture to spaces and displays. Because they are suspended, it is easy to adjust their final position and height to maximize the effect.

They are strongly rooted in the wabi-sabi philosophy so it is always a matter of “less is more.” Don’t overstyle kokedama by cluttering too many objects around them. Use them as you would a beautiful painting or artwork.

Use green plants with green-covered kokedama to add lushness to a stark corner and to soften a room. Use small and delicate kokedama where they can be appreciated at closer proximity and where they won’t become lost or obscured by too many other objects.

Choose large, lush, green leaves for backgrounds of soft texture to add drama.

Use delicate, structural branches and leaves against large, blank backgrounds to draw the eye to the detail. Use the height of the kokedama to focus the eye where you want it to go.

Combine finely detailed plants with large, monocolor objects for contrast and visual drama.

Be careful when hanging against walls, as the moisture from the ball can cause damage. If the surface is porous, there will be a risk of mold and mildew developing where the kokedama is touching it. Be sure to use a hook or hanger that protrudes out from the wall enough to avoid contact.

Make sure that the light is right for the plant; many plants used indoors prefer not to have sun touch them directly on their foliage or flowers. That is not to say they like darkness; most, in fact, need good, bright light. You can achieve this by hanging them so their foliage sits above or beyond the limit of the sun’s rays penetrating into the room.