During the Middle Ages, tapestries were among the highest luxury items in Europe, afforded mostly by royal or wealthy families and religious institutions. They were prized by kings and noblemen for their splendor, portability and practicality. In addition to being high quality and beautiful, they could be rolled up and easily moved between locations and even taken into battle, or hung on the walls of castles and palaces to keep them warm and provide sound acoustics.

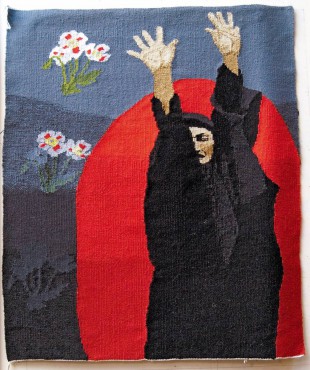

The materials and techniques used in hand-woven tapestries have evolved through the years, but the art continues to be highly prized, used as heirloom pieces in private homes and as public art in buildings. The tradition of tapestry weaving has remained strong in Europe and has been growing in the United States.

“We keep hearing it’s the hot new medium (in the United States), but there is no institutional nurturing — it’s not taught in art schools,” says Margo Macdonald, a Vaughn artist who has used tapestry as a medium for more than two decades.

“We keep hearing it’s the hot new medium (in the United States), but there is no institutional nurturing — it’s not taught in art schools,” says Margo Macdonald, a Vaughn artist who has used tapestry as a medium for more than two decades.

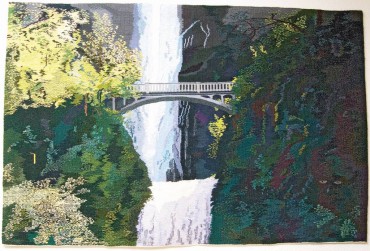

Macdonald herself is largely self-taught. Nearly three decades ago, she needed to find a new medium as an artist in order to get away from the smell of paints (she was a new mother). She discovered tapestries, and realized she could “paint” with yarn. An art teacher and a versatile artist who has created everything from watercolors to three-dimensional pieces, she focused on tapestry as her primary medium for many years, and received various recognitions for her work. Now, she goes between weaving and painting, which provides her with a “nice balance.”

“The images are similar, but (weaving) gives me a chance to process things differently,” she says. “I like the process. It’s like meditation. I like the slowness… because it gives me time.”

“The images are similar, but (weaving) gives me a chance to process things differently,” she says. “I like the process. It’s like meditation. I like the slowness… because it gives me time.”

Time may be described as the third dimension of this art form, which requires a great degree of patience. “You get so involved in it, you lose track of time,” says Cecilia Blomberg, a Swedish-born artist who specializes in tapestry. Blomberg, who lives in Gig Harbor, says she stumbled into tapestry while attending the National College of Art, Craft and Design in Stockholm, where she went to weaving school and also received the equivalent of a master’s in fine arts. A full-time artist for about three decades, Blomberg has been commissioned for numerous tapestries, some of which are displayed in public places including the BPA headquarters in Portland, Ore., Washington State University’s Vancouver campus and Grace Harbor College in Aberdeen.

“There’s something in the translation I really like, the interpretation of a sketch or image. I find the materials so beautiful,” Blomberg says. “There is a warmth in it and an element of surprise — you weave from one end to another and cover it up until you unravel it all.”

“There’s something in the translation I really like, the interpretation of a sketch or image. I find the materials so beautiful,” Blomberg says. “There is a warmth in it and an element of surprise — you weave from one end to another and cover it up until you unravel it all.”

Tedious Work

Tedious Work

From a distance, a tapestry may look no different than a painting, with intricate colors and realistic imagery. In fact, tapestries have been used for ages to tell stories, from the explorations of ancient Greeks to mythical tales of kings.

“Tapestry weaving is like painting, like any other art form — you’re creating an image, a piece of art, not just making fabric,” Macdonald says. Yet tapestry requires not only a different skill but also a much different approach. A painter may have a faint idea before starting the work on canvas with the brush. A tapestry weaver, however, has to have a solid design before the hands are ready for the warp and weft. Tapestry weaving is much more unforgiving: The artist can go back for minor tweaks, but major mistakes require painful alterations.

“It’s a much quieter time. Painting is much more active, you’re engaged in the whole image at one time. In tapestry, most decisions are made before you even get on the loom, and it’s a matter of translating the image. It’s less intense,” she says.

It may be less intense but it’s certainly much more time consuming. Macdonald can accomplish about an inch a day on smaller pieces, and large tapestries could take months to finish.

Although the term tapestry today is used for various stitched textiles, a true tapestry is hand-woven using a loom. It is different from the more utilitarian textile weaving. Vertical threads, called the warp, stretch tightly between the loom’s two beams, and horizontal threads, called the weft, are used to weave the image. Most tapestries use the simplest form of weaving — with the weft passing one warp thread over and the next one under — which allows the artist the most flexibility in interpretation of the image. The artist uses multicolored bundles of specialized yarn, and the weft changes every time there is a color change (the technical term, according to Macdonald, is “discontinuous weaving”). The weft is tightly packed, so the warp is not detectable in the final work.

The design may come from different sources, such as illustrations or photographs. To be “transferred” to the loom, it must first be transformed into what is called a cartoon, a full-scale sketch attached behind the warp to serve as a guide. The original photo or illustration serves as a reference, and the artist will use different techniques based on the desired effect. Macdonald says learning the technical part is easy, and mastering the art is easier for those who come from an artistic rather than weaving background. “For the artist, the image comes first and the technique is secondary,” she says.

The design may come from different sources, such as illustrations or photographs. To be “transferred” to the loom, it must first be transformed into what is called a cartoon, a full-scale sketch attached behind the warp to serve as a guide. The original photo or illustration serves as a reference, and the artist will use different techniques based on the desired effect. Macdonald says learning the technical part is easy, and mastering the art is easier for those who come from an artistic rather than weaving background. “For the artist, the image comes first and the technique is secondary,” she says.

Grandiose Works

Grandiose Works

During the height of this art, large-scale professional workshops were abundant in several parts of Europe. In those days, weavers were all men, and the workshops had a very hierarchical structure, with a master weaver in charge of the process, including the techniques and the colors. Modern European studios continue this tradition, answering the demand for tapestries commissioned as public art.

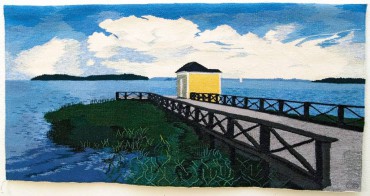

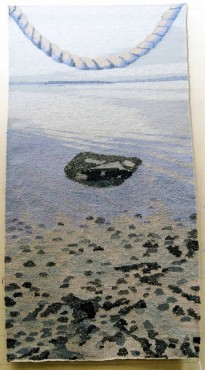

A few years ago, Macdonald and Blomberg decided to tap into that sort of collaboration. With Olympia artist Mary Lane, they created Pacific Rim Tapestries with the goal of obtaining larger commissioned work. Their third and most recent work was a series of three tapestries for Mary Bridge Children’s Health Center in Tacoma. The tapestries are 5-foot by 8-foot each, and are located near the elevators on each floor. Each depicts a theme: the sea, the land and the sky. They were illustrated by Blomberg, and took a year to complete, with all three of them working on them full time or nearly full time for a big part of the year.

A few years ago, Macdonald and Blomberg decided to tap into that sort of collaboration. With Olympia artist Mary Lane, they created Pacific Rim Tapestries with the goal of obtaining larger commissioned work. Their third and most recent work was a series of three tapestries for Mary Bridge Children’s Health Center in Tacoma. The tapestries are 5-foot by 8-foot each, and are located near the elevators on each floor. Each depicts a theme: the sea, the land and the sky. They were illustrated by Blomberg, and took a year to complete, with all three of them working on them full time or nearly full time for a big part of the year.

On a collaborative project, the three artists work side by side, mentally splitting the “canvass” in three and trying not to get too far ahead or behind from each other.

On a collaborative project, the three artists work side by side, mentally splitting the “canvass” in three and trying not to get too far ahead or behind from each other.

“To make it a unified image, you have to agree on technique and style,” Macdonald says.

Knowing each other for 10 years and being friends helps the Pacific Rim Tapestries artists create such unified works. But what if they had to work side by side with strangers?

Blomberg recently returned from a two-year project in Scotland, where she worked on part of a tapestry measuring about 140 square feet with weavers she has never met before. It wasn’t an ordinary tapestry either, but a re-creation of one of the seven “The Hunt of the Unicorn” tapestries that are considered among the finest in the world — the only project of its kind, ever. The originals are displayed in the Cloisters Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Blomberg worked at Stirling Castle on the third tapestry, called “The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle.” Work on the third tapestry started in 2004, and Blomberg joined the project in July 2005.

Her team included a senior weaver from United Kingdom and another weaver from Australia, who was later replaced by another from Japan (most weavers only commit to two-year participation). They worked on a rolling schedule in public view, and conducted public presentations every day. Some days, the studio had more than a thousand visitors, and often times the weavers had to use their MP3 players to tune out the background discussions and concentrate on their work. The tapestry, which was woven sideways, grew by an average of one inch per week.

Her team included a senior weaver from United Kingdom and another weaver from Australia, who was later replaced by another from Japan (most weavers only commit to two-year participation). They worked on a rolling schedule in public view, and conducted public presentations every day. Some days, the studio had more than a thousand visitors, and often times the weavers had to use their MP3 players to tune out the background discussions and concentrate on their work. The tapestry, which was woven sideways, grew by an average of one inch per week.

Blomberg left before the cutting of the tapestry this past August, but she got to see the finished work hung in the studio. “That was really fantastic,” she says.

Blomberg left before the cutting of the tapestry this past August, but she got to see the finished work hung in the studio. “That was really fantastic,” she says.

She is very glad to have pursued the challenge and to have had the opportunity to study such a grand piece of history as well as help re-create it. “I feel everything I have done up to this point was so I can do this,” she says. “And I really enjoyed working in front of people; it was such a great educational experience.”

Blomberg was just settling back in her home and her studio in October, and was looking forward to noting how this experience will influence her future work. And with her return, the Pacific Rim Tapestries artists were poised to relaunch their collaboration.

Macdonald says the more people learn about this ancient art, the more they appreciate it. Tapestry, she feels, holds a special connection, both with the artist and with the viewer. “The tapestry has a real presence to it; paintings don’t resonate the same way,” she says. “Maybe it’s easier to identify with a tapestry because you can touch it, which makes it more approachable.” As for the artist, she says weaving using techniques and tools that have been around for centuries is like playing classical music.

“You feel connected… to all those weavers who sat at the loom before you for thousands of years,” she says. “The more time you spend on it, the more you appreciate it.”