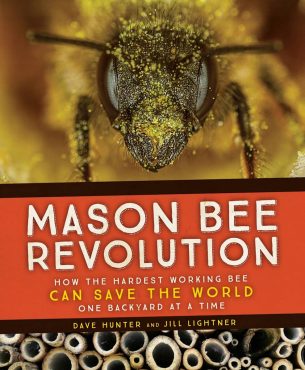

(Photo courtesy Dave Hunter/Crown Bees)

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from “Mason Bee Revolution: How the Hardest Working Bee Can Save the World One Backyard at a Time,” a book by Dave Hunter and Jill LIghtner recently released by Seattle-based Mountaineers Books. In Part 2, learn about the benefits of pollen in the garden as well as reduced chemicals due to mason bees.

When people hear “beekeeping,” the image they picture is almost always of honey-bee keepers in white, helmeted spacesuits fretting over their hives for hours at a time and purchasing fairly heavy-duty equipment just to get started. But the options for home beekeeping are far more interesting than that image evokes, and many are much, much simpler.

Social vs. Solitary

There are thousands of species of bees around the world, about 4,000 of them native to North America. A casual observer might divide them into four basic categories: honey bees, the ones in such headline-grabbing peril and requiring those goofy spacesuits for their keepers; wasps, the ones that are nearly universally loathed; hornets, who bother us all too frequently at our picnics; and bumblebees, the cartoonishly cute teddy bears of the bee world.

All these flying bugs, excepting a few species of wasp, are social insects that live in families of anywhere from 50 to a few thousand members, and work together to build and maintain their home, collect and store food, and protect their queen.

The big surprise for that casual observer is that these social bee species make up only about 10 percent of all North American bees, while the remaining enormous majority are of a completely different type. These other thousands are called “solitary bees.”

The category of solitary bee encompasses many different habits — an easy example is that some prefer underground nests, while others like their homes higher up — but many of them are excellent pollinators.

Of the solitary species, the mason bee is one of the very earliest bees to appear in the spring, which means that your springtime garden will derive the maximum benefit from its pollinating efforts. The name “mason bee” can refer to a number of different species of bee, all of which are solitary.

Of the solitary species, the mason bee is one of the very earliest bees to appear in the spring, which means that your springtime garden will derive the maximum benefit from its pollinating efforts. The name “mason bee” can refer to a number of different species of bee, all of which are solitary.

They are members of the Osmia genus of bees, which can use either soil or material sourced from plants in their nests. Depending on the region where you live and how formal the discussion, in North America you might hear them called orchard mason bees, blue orchard bees, orchard bees, or spring mason bees.

Whichever name they go by in your area, they are almost certainly the species formally known as Osmia lignaria. These North American natives were busily pollinating this continent for millennia before the European honey bee arrived, and they are actually far better at it.

Different Bees, Different Behavior

Honey bees are designed to tidily capture pollen to bring back to their nests. They are so focused on this job, and so efficient at packing the pollen into a body part called a pollen basket, that very little gets dropped. Pollination is fairly accidental with them, only happening when they are sloppy at work.

Mason bees, meanwhile, also want to carry pollen back to their nests and have fuzzy abdomens where it is collected loosely, with a certain tendency to drop off the bee’s fuzz as easily as it came aboard. To collect it, the bee crawls slowly all over a blossom, gathering pollen and dropping it again as she flies erratically from flower to flower.

It is probably a good thing mason bees are solitary, as they would be annoyingly sloppy coworkers in the hive, compared with the oh-so-efficient honey bee.

Their fuzzy bellies and here-and-there flying habits make mason and leafcutter bees truly exceptional pollinators. Honey bees may get the attention in commercial crops, but part of the reason is that their keepers end the pollinating season with products they can sell, namely honey and beeswax.

Because these earn a relatively high price per pound for a small farmer keeping his own bees, there is an obvious appeal. But in the case of a large agricultural operation, chances are they will just hire the honey-bee pollinator service that offers a good price and is available when needed.

If small farms or large orchards are only in need of pollination, mason bees, while different, are a wonderful alternative. A single mason bee can pollinate enough cherry blossoms to net 12 pounds of fresh cherries. In comparison, a cherry orchardist needs 60 honey bees for the same size harvest.

Scale up to a fairly small commercial orchard of 50 trees, and the mason bee provides a remarkable benefit to the orchardist. Its dry pollen-carrying technique simply gets more blossoms pollinated, making it an ideal addition to any orchard.

Honey bees do offer some basic advantages for commercial operations: For one thing, they come with their houses, so orchardists do not have to invest in and maintain bee boxes. Honey bees also travel with their own food supply, which means they can be brought into an orchard just before the blossoms open — they are ready and waiting in position for the starting gun to fire, so to speak.

Another issue is that the chemicals that orchardists might be spraying on trees have likely been tested for safety on honey bees but not necessarily any other kind of bee. We are only now learning that these “bee-safe” chemicals may not be healthy for our native mason bees and other wild bee species; this is true both for orchard sprays and for chemically treated seeds.

Dave Hunter and Jill Lightner are the authors of the newly released book "Mason Bee Revolution: How the Hardest Working Bee Can Save the World One Backyard at a Time," published by Seattle's Mountaineers Books. While you can't harvest honey from mason bees, you can create a robust urban garden, encourage healthy crops in your city and help safeguard our food supply. The book explores the facts (and fictions) of pollination and food production, with a focus on how mason bees can help everyday gardeners get more from their own fruit trees, berry patches and vegetable beds. For more information, go to www.mountaineersbooks.org.