overlooking the inlet

On Bainbridge Island, looking out onto Manzanita Bay, Navy veteran Al Philips has been assembling a collection of native plants around his home. Soon after purchasing his lot, Philips began landscaping. At first, he planted all sorts of plants, but soon a love of native plants took hold and he began exclusively planting natives only.

A few decades later, Philips’ land is a collection of native ferns, shrubs, trees and herbaceous species.

Philips served as a submarine petty officer during the Vietnam War. Later, he rose to the rank of lieutenant commander before finally retiring from the Navy in 1992. Now he is an electrician and instructor for electrical continuing-education courses. He has also assisted renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly in materials and design to develop safety glass — glass that won’t break so it can be safely displayed overhead.

The Navy veteran’s parcel, which he purchased in 1973, comes with a bit of history. In 1855, land that includes Philips’ plot was settled by Charles Olson. Philips had the opportunity to talk to Olson’s grandson (born in 1919). He learned part of the original Olson purchase (but not Philips’ parcel) was an abandoned Suquamish village site and Olson traded milk for salmon with the Suquamish.

The original Suquamish habitation of the land dates at least as far back as a thousand years. A low bank on the west side of Bainbridge Island and access to fresh water and salmon made the location an ideal village site. A midden near the water’s edge on Philips’ parcel contains shells of the Olympia oyster, a species that has been in decline for decades and is locally extinct from Bainbridge Island.

Since the Olson settlement, the land has been logged three times — in 1880, 1910 and 1952. Then, after the 1952 logging, the land was platted into 30 lots, two of which Philips purchased.

His plot is approximately one acre of upland habitat and one acre of estuary. Since moving in, he has seen the shoreline eroded about 5 feet and Philips eventually installed a concrete bulkhead to preserve the older conifers. In the 46 years that he has owned the property, he has also noted a substantial increase in trees.

The trees have all grown up in that time and the once younger-feeling lot now sports some large trees. Some large enough that they even may be survivors of the most-recent logging episode. One cedar, now 5 feet in diameter, has increased a full foot in width since Philips purchased the plot. Nearby, a large cedar and Douglas fir have grown together, and Philips refers to them collectively as the “marriage tree” because he and his wife were married next to it.

Philips began planting his land in 1974, soon after purchase. As his interest in native plants kindled, he took a botany course from the University of Washington. Unfortunately, the class at the time taught little in the way of native plants so he endeavored to learn by other means. Some things he gleaned from knowledgeable neighbors but he also began to teach himself and in the ’80s, Philips taught himself to key out plants using technical botanical keys.

As much as possible, Philips has adopted a strict definition of “native.” Starting with plants that occurred on the original property, slightly over half of all species, he added plants collected from Bainbridge (30 percent) and finally, with few exceptions, planted species that are not only native within 50 miles of his home but also sourced within 50 miles. While this is difficult with many natives, this tactic lends a degree of authenticity to his garden.

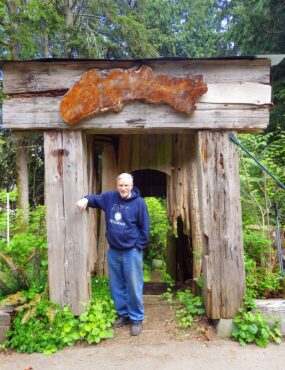

Up by the road, a large, old-growth stump with a hole carved through it serves as the gateway to Philips’ garden. In August, he opens the garden to a tour provided through the Bainbridge Island Metro Park & Recreation District. Tour attendees pass through the gate into a reception area surrounded by green native vegetation, the first area in different garden sections showcasing differing native species and habitats.

The reception area is a forested understory habitat underneath western redcedar, bigleaf maple and western hemlock. In the spring, wake robin (Trillium ovatum) appears, followed by false lily of the valley (Maianthemum dilatata). Green ground covers include wood sorrel (Oxalis oregona) and lady fern (Athyrium felix-femina).

From there, a trail takes visitors down a gentle slope passing through more understory habitat with red huckleberries and more wake robin. Fringe cups (Tellima grandiflora) also send greetings from the forest floor. At the end of this trail is a pond that Philips created for shade-loving water plants. Specifically, skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) loves the pond and thrives in the submerged pots Philips planted them in for ease of handling.

From the pond, the trail heads to a partially eroded bank over the estuary below Philips’ land. At the top is the creamy-flowered ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor), a twiggy, large shrub. A small collection of native ferns grows along the bank, above the concrete bulkhead Philips installed to protect an old 5-foot-diameter Douglas fir and slow erosion.

Scouler’s polypody (Polypodium scouleri), a relative of the more common licorice fern, is present. Normally it is found over on the coast grown on the trunks of Sitka spruce. The native western maidenhair fern (Adiantum aleuticum) is also planted in the area.

Planted on the exposed soil of the bank is narrow beech fern (Thelypteris phegopteris), an uncommon fern that can be found on steep, shady banks above the beach on Bainbridge Island. Philips traded licorice fern to get the giant chain fern (Woodwardia fimbriata), also rare on Bainbridge, and they are placed for visitors to examine easily.

After a view of the estuary, the trail leads back up and visitors will pass a small 10-by-10-foot square dry spot. This spot is dry enough and sunny enough that Philips chose to plant species native to Western Washington that prefer drier sites. All are native locally, within 50 miles or from the San Juan Islands, and the planting lets visitors experience species they are unlikely to find in the local woods.

Rocky mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) does well in the dry spot and is kept company by two other trees: western larch (Larix occidentalis), which has eye-gripping yellow fall color; and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). Ponderosas are more typically associated with Eastern Washington but rare western populations are known on dry, sunny locations. There is a notable group of ponderosas at Fort Lewis. Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium) and kinnikinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) are also happy at Philips’ dry site.

Continuing up the trail, visitors will encounter Alaska cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis), whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis) and subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) — tree species common at higher elevations. Those familiar with the Olympic Mountains flora may recognize Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) planted here too. This section of the trail is like a mini arboretum of trees native to the mountains of Washington state.

The final stop before completing the loop is a second, sunnier pond. Visitors cross a little bridge and can view various water-loving species. This spot possibly has the highest concentration of species in Philips’ garden. One of the smallest is duckweed, a mass of floating, roundish plants that are among the tiniest plants on earth. They are often mistaken for algae but they are vascular, flowering plants although their flowers are rare and easily overlooked.

In the shallower spots are giant bulrush (Scirpus lacustris) and small-flowered bulrush (S. microcarpus) hiding tadpoles and newts. Just out of the water is the yellow-flowered silverweed (Argentina anserina), a native lover of soggy soil and sunlight. Larger shrubs and small trees in the area include mock orange (Philadelphus lewisii), chokecherry (Prunus emarginata) and black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii).

After enjoying the pond, visitors will have experienced many of the area’s native plants, trees and shrubs and seen that they can be grown in gardens. In past years, Philips’ collection has been accessible during the tour offered through Bainbridge Island’s park district. Hopefully that will be possible this year, but native plant lovers may have to wait until 2021.