Jan Walker’s writing studio reflects the eclectic body of her work — literary magazines, professional journal short stories, articles and educational curriculum, as well as the occasional penning of a newspaper editorial about prison reform. Her equally eclectic life could fill a book. And it does — she’s also the author of 12 fiction and nonfiction novels.

Jan Walker’s writing studio reflects the eclectic body of her work — literary magazines, professional journal short stories, articles and educational curriculum, as well as the occasional penning of a newspaper editorial about prison reform. Her equally eclectic life could fill a book. And it does — she’s also the author of 12 fiction and nonfiction novels.

A product of the West Sound, Walker grew up in North Kitsap surrounded by Scandinavian relatives while attending Brownsville Elementary, where her mother taught. That heritage and her family members figure into her writing.

“I like including my dad in my stories,” she said. “I have vivid memories of him. Sometimes the characters in my books say what my father might say as though he’s talking to me while I write.”

Her mother is featured in a short story about the World War II lives of Puget Sound Naval Shipyard families.

Her mother is featured in a short story about the World War II lives of Puget Sound Naval Shipyard families.

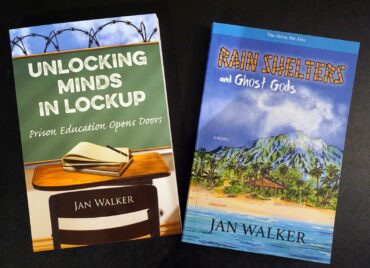

“A Farm in the South Pacific” is her novel based on the life of an entrepreneurial cousin, a woman who moved to the Kingdom of Tonga to open a spiny lobster nursery before settling in Hawaii. There, Walker visited her regularly and after inheriting her cousin’s journals and photo albums, used them as research for that novel and her most recent book, “Rain Shelters and Ghost Gods.”

She’s always been a writer. “I had a great high school teacher who told me I was good. That was inspiring,” she said. “In college, I helped people write their term papers and published short stories and textbooks before I ever published my first novel.”

Her debut book, “An Inmate’s Daughter,” published in 2006, is a young adult fiction novel that earned recognition from the Washington State Library program. The plot, she wrote, “focuses on prisoners’ families, family secrets, peer pressure, race awareness and a father who used his time in prison to improve his parenting and family relationships.”

Her debut book, “An Inmate’s Daughter,” published in 2006, is a young adult fiction novel that earned recognition from the Washington State Library program. The plot, she wrote, “focuses on prisoners’ families, family secrets, peer pressure, race awareness and a father who used his time in prison to improve his parenting and family relationships.”

Her familiarity with life inside the prison fence is well-earned. She spent over two decades as an instructor and volunteer at three of the state’s penal institutions: McNeil Island when it was a federal penitentiary, Washington Corrections Center for Women in Purdy and Belfair’s Mission Creek Corrections Center.

Among her many other skills include tailoring her own clothes while teaching parenting and basic life classes at Tacoma Community College. When the state Legislature required community colleges to offer education inside the state’s prisons, The Women’s Center in Purdy asked the college to send someone who could teach home and family-life classes and sewing. Walker committed to one year and ended up teaching in the prison system for 18.

Among her many other skills include tailoring her own clothes while teaching parenting and basic life classes at Tacoma Community College. When the state Legislature required community colleges to offer education inside the state’s prisons, The Women’s Center in Purdy asked the college to send someone who could teach home and family-life classes and sewing. Walker committed to one year and ended up teaching in the prison system for 18.

“When I arrived, they handed me the textbook for teaching family relations,” she said. “It was written for ninth-graders and so unsatisfactory for the women I taught who needed different information. They needed to know about interpersonal relationships and self-esteem.”

So, she wrote and published a nontraditional text for her students titled “My Relationships, Myself.” The book became one of her first attempts to change the prison’s course offerings.

In her memoir, “Unlocking Minds in Lockup,” Walker describes what it was like to teach inside and says she quit when the Legislature’s new, “tough-on-crime” philosophy defunded classes. She remains an advocate for prison reform and has since written additional works for the public and prison employees about incarceration and its impact on children of incarcerated parents.

“Oddly, the system didn’t leave me,” she writes in her memoir. “I turned to writing fiction.”

“Oddly, the system didn’t leave me,” she writes in her memoir. “I turned to writing fiction.”

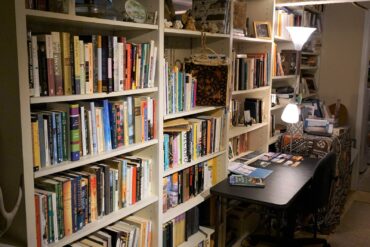

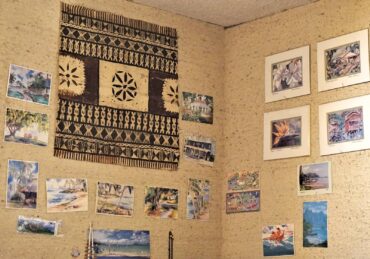

Her cozy writing studio in rural Gig Harbor belies her familiarity with the stark walls of a penitentiary classroom. The studio’s walls are lined with family photos and memorabilia of her travels and work. Bookshelves overflow, revealing her interests in history, nature and legends. The neighborhood deer drop by, pressing their noses against the room’s sliding doors to observe.

She describes her fiction as literary and character driven — a Norwegian family in Poulsbo, Slavonian fishing families in Tacoma and Depression-era family life in Brownsville.

“Two of my novels, ‘An Inmate’s Daughter’ and ‘Romar Jones Takes a Hike: Runaway or Missing Person,’ feature the struggles of children of incarcerated parents,” she said.

Each novels begins its life on photo story boards and in handwritten notebooks marked with sticky notes. Walker’s writing is descriptive and she’s a stickler for accuracy. Close-up photos of a shell ginger leaf ensure details are correct when they appear in a book set in Hawaii. So do photos of Poulsbo’s Front Street. From there, she transfers the emerging story to computer, often working on multiple writing projects simultaneously.

Recently, neat piles of works in progress were organized on two large desks in her office. There were the beginnings of two new fiction books and plans to update her textbook for prisoners, “Parenting From A Distance.” She was finalizing an upcoming online memoir writing course titled “Writing From Life: The Power of Story.” And she blogs regularly on her website — musings about the pandemic or the back story about her latest novel.

Recently, neat piles of works in progress were organized on two large desks in her office. There were the beginnings of two new fiction books and plans to update her textbook for prisoners, “Parenting From A Distance.” She was finalizing an upcoming online memoir writing course titled “Writing From Life: The Power of Story.” And she blogs regularly on her website — musings about the pandemic or the back story about her latest novel.

As if multiple writing projects weren’t enough, Walker also runs a publishing company. When she and other local writers realized there was a need for a small, independent cooperative press, she launched Plicata Press in 2010. She serves as both publisher and editor, to date shepherding 20 books by 12 different authors through the process.

At age 83, Walker finds inspiration for her stories in her own life experiences and artifacts, but they’re driven by her purposeful life — multitasking, writing, teaching, running a business and advocating for prison reform.

“Writers will tell you that writing is solitary work,” she wrote in her memoir. “Most also will tell you it is deeply satisfying. Along with the power of story, I believe in the power of putting pen to paper.”